In its boldest step yet into medicine and health, Apple unveiled on Monday software that lets iPhone users participate in clinical trials, and a smartwatch that monitors individuals' fitness levels. It's the company's first foray into ever-present, wirelessly connected health tools.

The company had previously revealed the Apple Watch, with its ability to track steps and burned calories, and HealthKit, the tool for making iPhone health apps. But at today's keynote address, it unveiled a surprise suite of new software, called ResearchKit, that could have a significant impact on how patients receive care and how physicians give it.

"Perhaps the most profound change and positive impact the iPhone will make is on our health," Apple CEO Tim Cook told the audience at San Francisco's Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater this morning. "There are already over 900 incredible apps that help you manage and track your health and fitness. But we have always wanted to make the biggest difference we could make. As we work on HealthKit, we came across an even broader impact that the iPhone could make — and that is on medical research."

A clinical trial in your pocket

Apple executives said ResearchKit is intended as an antidote to some of the factors that traditionally hamper clinical trials: small sample sizes, which can skew the accuracy of results; diagnoses or assessments colored by individual physicians' subjectivity; and infrequent data intakes, which can paint an incomplete portrait of a patient's health.

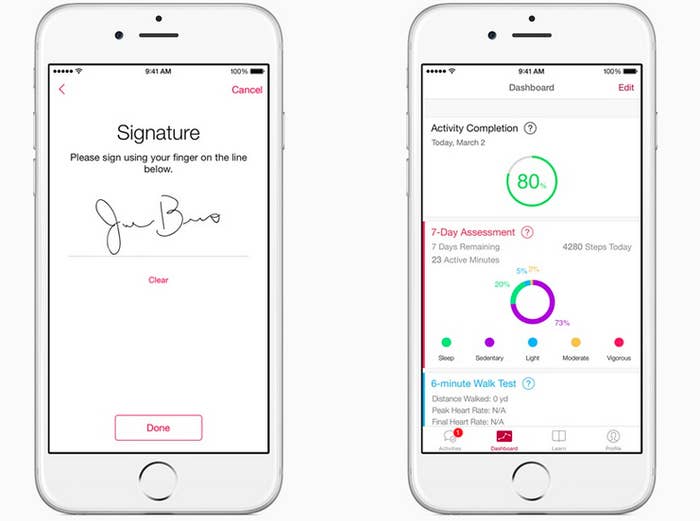

ResearchKit is an open-source tool that will enable researchers to create apps that diagnose or track diseases by using the iPhone's sensors in real time. The first five apps, available starting today, will facilitate studies for diabetes, breast cancer, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and Parkinson's disease. They'll link to participating research institutions that include Stanford University, the University of Oxford, Weill Cornell Medical College, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, UCLA, and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

In the case of the Parkinson's app, for example, the phone will measure the users' hand tremors. Users can also say Ahhhh into the microphone, and the phone's processor will detect slight vocal-chord variations that assess their level of Parkinson's. The phone can even track performance on the six-minute walk test, a common way to assess the disease: Users would stick it in their pocket and its accelerometer and gyroscope can measure their gait and balance.

"And you can do that anywhere — not just in the doctor's office," said Jeff Williams, Apple's senior vice president of operations.

He added, "Exercise can affect symptoms of Parkinson's, but some believe exercise may actually slow or even halt progression of Parkinson's. Now researchers get a chance to look at that data."

ResearchKit will also pool iPhone-collected data with external data, Williams said. For the asthma app, for example, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine and Cornell's medical school will give away Bluetooth-enabled inhalers to patients to accurately measure their asthma. Those researchers also plan to swab various surfaces throughout New York City and match the geolocation data of both the pathogens and patients' asthma attacks in an attempt to identify asthma triggers.

ResearchKit will be released to the research community at large in April, Williams said.

Medical data is perhaps the most personal kind of data, and patient privacy advocates are generally wary of how companies handle and protect it. Williams sought to make clear that Apple itself will not collect this data. "You decide what apps you participate in, what research you participate in," he said. "You decide how your data is shared and Apple will not see your data."

But Apple did not address security, a sensitive issue in the light of the recent hack into 80 million Anthem health insurance consumers.

The Apple Watch: slimmed down, but still tracking your moves

Meanwhile, the Apple Watch, which customers can preorder starting April 10, is meant to measure much more basic fitness indicators. As previously announced, it will measure users' activity levels, distance traveled, heart rate during workouts, and calories burned. The watch, whose cost will range between $350 and $10,000, will use that data to generate goals for users — for example, to aim to burn more calories than in the prior week.

Supermodel and maternal health advocate Christy Turlington Burns appeared in a video and on stage during the keynote to discuss how the watch helped her run in a half-marathon in Tanzania.

The Apple Watch is not the perfect health tracker. A battery life of 18 hours means data monitoring won't be continuous, and some users may get frustrated or forget to charge it. Apple reportedly yanked more advanced biosensors, like detectors for blood pressure, because they weren't accurate or made the watch too similar to the medical devices regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

The watch could still be a helpful fitness device, however — precisely because many of its consumers won't buy it with the intent of tracking their fitness. If millions of people buy one, as Apple is hoping, at least some of them won't be health-conscious.

But as they poke around the watch's colorful interface, on their way to make a call or text a friend, they may come across the calculations of how many calories they've burned, how much they've exercised, and how long they've been sitting instead of standing. And at least some users will start regularly checking those metrics and moving around more to improve their numbers. After all, if Apple has designed its watch correctly, it'll be effortless to glance at that tiny screen and get a sense of your progress.

Through the developers tool HealthKit, the Apple Watch will both integrate with and show notifications from third-party apps. That means health apps can light up the screen or send out vibrations to remind you to, say, take a walk. The opportunity to send those suggestions to the wrists of potentially millions of people is an opportunity health apps haven't had before.

Apple's impact in health will only be as big as the demand for its devices. And if the company's track record is any indicator, health care could undergo some significant transformations indeed.