Between the ages of 14 to 17 (and, if I’m being honest, even now) I spent most days looking out the window and crying while listening to a Sufjan Stevens song. “Casimir Pulaski Day” — a song about cancer, God, queerness, and Michigan — rattled my emotional cage so much that even hearing him count at the beginning of the song makes me well up. (That I had never had cancer, knew anyone with cancer, didn’t believe in a Christian God, was not queer, and have never lived in Michigan didn’t matter.)

Sufjan’s music was the soundtrack to all my heartbreaks and all my sadness. I listened to him when I was dumped (often!), when my parents dropped me off for university for the first time (I feel weirdly blessed that Sufjan didn’t release his latest mom-themed album, Carrie & Lowell, in 2015), and whenever I wanted to languish in the comfort of feeling sad (often!). At Christmas, a holiday I have no attachment to and no real interest in, I’d listen to “That Was the Worst Christmas Ever!” and feel as if I, too, had a terrible Christmas. Listening to his music was a frequent routine; my gentle bedroom sobbing would only be interrupted when my mother would knock on my door and say, “Well, now what?” and I’d lift my head off my pillow and eke out nothing more than, “It’s Sufjan, mother.”

I don’t admit to crying this much freely, but when it comes to listening to Sufjan, I figure it comes with the territory. It’s hard to escape the experience emotionally unscathed.

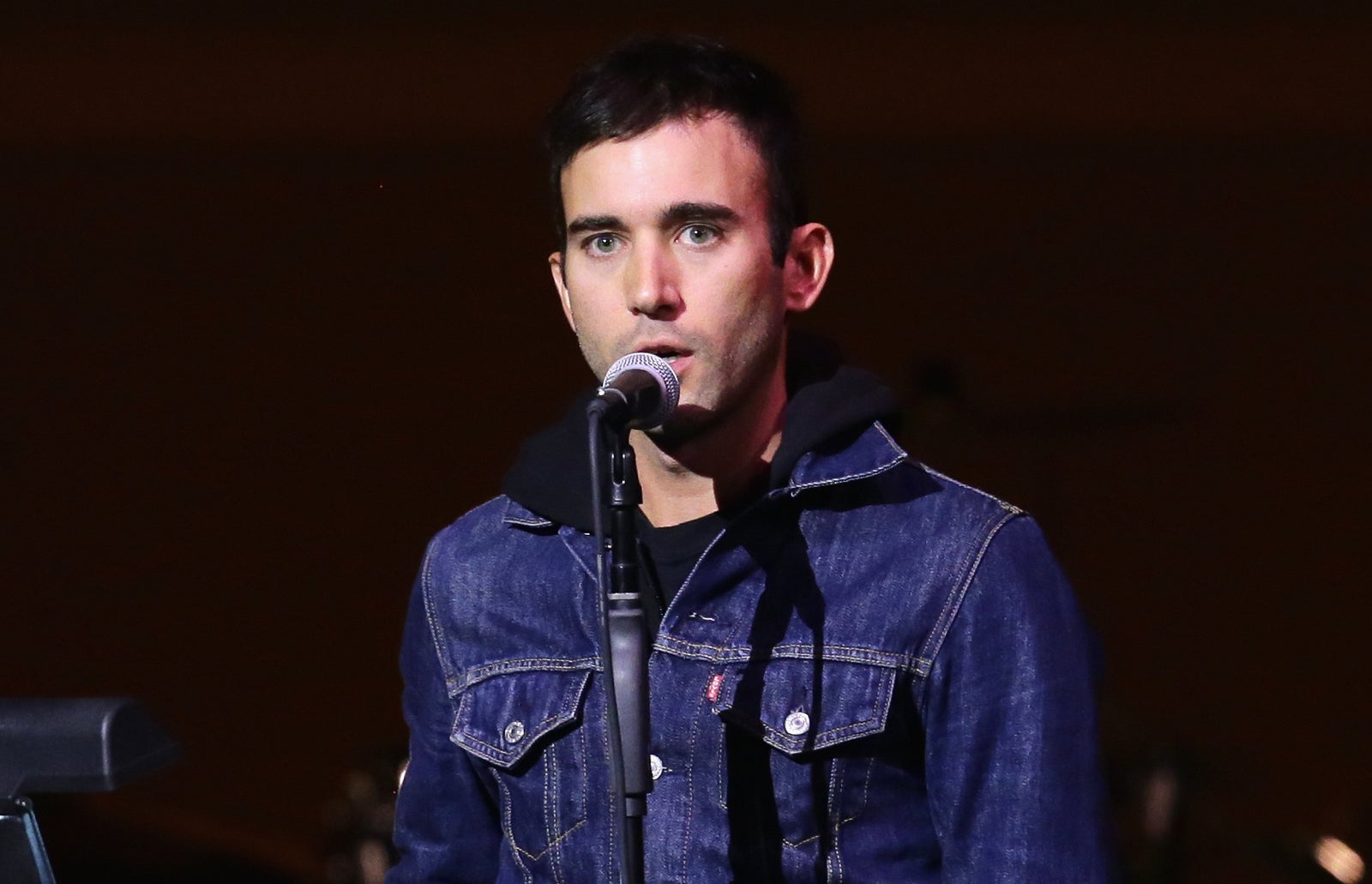

At 42 years old, Sufjan has been a quietly successful staple of the indie/alternative music scene for the past 18 years, even if his mainstream success is only relatively recent. He’s released seven studio albums since his first in 2000 and embarked on a number of tours (including the 24-stop “Surfjohn Stevens Christmas Sing-A-Long: Seasonal Affective Disorder Yuletide Disaster Pageant on Ice” in 2012). His songs are recognizable staples across different mediums, from hip-hop (Kendrick Lamar sampled him in “Hood Politics,” and Sufjan’s song “Michigan” inspired the Roots’ 2011 album Undun) to film and TV (his songs have been featured in Little Miss Sunshine, Veronica Mars, The O.C., Weeds, and Friday Night Lights). And then of course, his most recent claim to fame are his two original songs for Call Me by Your Name, “Visions of Gideon” and “Mystery of Love” (there’s also a remix of his 2010 song “Futile Devices” featured in the movie). All three songs became integral parts of the film, perfectly encapsulating the rush of new love and the heartbreak that occurs when you lose it.

On Sunday, Sufjan performed at the Oscars in light of his nomination for “Mystery of Love,” his first nomination of this scale — he’s never even received a Grammy nod before. The comparison between Sufjan’s performance — twee and beautiful, in the way things not already industrialized by Hollywood can be — is easily compared to Elliott Smith’s in 1998, when he was nominated for “Miss Misery” from the Good Will Hunting soundtrack. Smith performed in a white suit, alone with a guitar and his spidery voice. It was a stark comparison to the otherwise gluttonous event, and the eventual winner of the category, “My Heart Will Go On.” Somewhat similarly, Sufjan performed by popping out from the stage with a live band while wearing a pink and navy striped suit jacket with teal dragons running across it. It was simple, unfettered but eccentric, all-too-short, and wildly cute — an easy introduction to Sufjan if you've never heard him before. Both Sufjan and Elliott Smith are (or were) on the outside looking in, briefly invited to participate, quiet geniuses with cult followings and bodies of work that hit a depressing nerve.

His songs feel cathartic in a way, like a validation of your own feelings rather than a condemnation of them.

Ideally, a good time to find Sufjan is in your mid-teens, when everything hurts all of the time and you don’t yet have the language to articulate why. Sufjan’s music, often morose and beautiful, combined with his face — gap-toothed and boyish, make him the perfect, sexy, sad boy. His music expresses a unique vulnerability, like listening to someone recite a particularly absorbing and relatable diary entry. His songs are all about storytelling, remarkably unreliant on choruses, breathy and delicate, and even when he sings alone, he sounds choral. Though they traffic in unbelievable sorrow, his songs feel cathartic in a way, like a validation of your own feelings rather than a condemnation of them. And unlike someone like Elliott Smith, whose (tragic) image is all about whether you could save him from himself, Sufjan needs no rescuing. There’s a security in his sadness, because it also comes with wearable butterfly wings and impressive but approachable muscles. You can spend time with him in your depression without feeling like it’s impossible to climb out of it later. He has no idea how to wear a hat.

Sufjan is like the last pure response to toxic masculinity: While other men are trying to out-macho each other, (like Justin Timberlake taking to the woods and fucking robots or whatever) Sufjan is sitting in a meadow and strumming a banjo while offering up his feelings in clear, defined lyrics: “Did you get enough love, my little dove?” (Oh god, who put all these onions on my desk??) Listening to Sufjan is like getting a brief reminder that some men, somewhere, are willing to be sad with you, instead of being the reason you’re upset in the first place.

That Sufjan is an enigma, especially in an industry that demands access to our preferred musicians, makes him even more appealing. He has no social media, gives few intimate interviews, and rarely makes music videos. (There’s one for a remix of “Life With Dignity” for the Cancer Support Community, an animated tiger cartoon for his 2014 song “Year of the Tiger,” and a stop-motion video for 2017’s “The Greatest Gift.” Predictably, he doesn’t appear in any of them.) Even Bon Iver, Patron Saint Of Reclusive Sad White Men Everywhere, made a few videos for his breakout album, For Emma, Forever Ago. Sufjan doesn’t even give that much. You’re often left to figure out the meanings of the songs yourself, which is maybe why people like him. You can attach yourself or your experiences to one of his songs without having to consider too much of the song’s original purpose.

Sufjan’s music was the soundtrack to all my heartbreaks and all my sadness.

Because he’s so unrevealing about his personal life, beyond what he sings in his music, his music sparks a lot of conjecture. Wide swaths of Sufjan’s songs have to do with Christianity, or also, maybe being in love with a man, which has sparked a cottage industry of thinkpieces (“We Can’t Stop Wondering if Sufjan Stevens Sings About God or Being Gay”) and playlists (“Is This Sufjan Stevens Song Gay or Just About God”). I spent half my teens pining for him, while also thinking that if he were gay, we could just be best friends, the kind who sometimes share a bed.

But Sufjan’s music is impossibly rife with meaning, however you want to look at it. “Casimir Pulaski Day,” off Illinois, is one of his most layered. The title is a specific nod to Chicago, while the song is at once about forbidden love, his maybe-lover getting bone cancer, and the ensuing crisis of faith that happens after they die. It also features references to a father’s possible suicide, the Illinois state bird (a cardinal, also a harbinger of death), and, possibly, Dante’s Purgatorio. Breaking down a Sufjan song is a near-impossible task, since most of his songs are rich with detail — from the personal to the literary to the geographical. Even his Christmas music (there is, truly, an ungodly amount of it) swings dramatically from fun, frolicsome joy (“Mr. Frosty Man”) to a much more morose tune (“Justice Delivers Its Death”). And I guess, if you’re going to be the most depressing artist in the world, you might as well carry some whimsy along with it.

Carrie & Lowell, Sufjan’s most recent full-length album, is the closest Sufjan has gotten to writing an autobiographical album. It’s a lot more dour overall than his previous work, but because it’s so intimate, it’s also full of affection and warmth. The record is about Sufjan’s mother, Carrie, who abandoned Sufjan as an infant and was in and out of his life before she died of stomach cancer. “She was evidently a great mother, according to Lowell and my father,” Sufjan told Pitchfork in 2015. “But she suffered from schizophrenia and depression. She had bipolar disorder and she was an alcoholic. … But when we were with her and when she was most stable, she was really loving and caring, and very creative and funny. This description of her reminds me of what some people have observed about my work and my manic contradiction of aesthetics: deep sorrow mixed with something provocative, playful, frantic.”

Which is exactly what makes Sufjan so lovable. When Sufjan isn’t coming off as the most depressing man in the world, he’s the human equivalent of a tiny bird landing on the tip of your finger and singing a sweet little song. Everything is twee, homemade, pure, innocent. At his live shows, he’s often in neon stripes, angel wings, sporting a sideways visor while playing in front of two horns, two drums, and countless guitars. It’s DIY-cute overload, but entirely self-aware. Take this song title from Illinois, for example: “The Black Hawk War, Or, How to Demolish an Entire Civilization and Still Feel Good About Yourself in the Morning, Or, We Apologize for the Inconvenience but You’re Going to Have to Leave Now, or, ‘I Have Fought the Big Knives and Will Continue to Fight Them Until They Are Off Our Lands!’”

Ideally, a good time to find Sufjan is in your mid-teens, when everything hurts all of the time and you don’t yet have the language to articulate why.

It’s this duality that keeps Sufjan from sounding myopic or navel-gazing in his sadness. Because he has moments of real humor (“Super Sexy Woman” from his 2004 album A Sun Came, is about an attractive, farting superhero), you don’t feel like Sufjan is in need of fixing. He’s secure in his complex, contradictory feelings. Which is why he was perfectly suited to write a few songs for Call Me by Your Name, a movie entirely about men coming to terms with their feelings. (But even having him involved in a movie soundtrack was a hard sell; Sufjan is generally picky about which projects he gets involved with, and largely played hard to get with director Luca Guadagnino. Initially, Guadagnino wanted Sufjan to appear onscreen, and read voiceover passages from the teenage protagonist Elio, but from his perspective as an adult. Sufjan convinced him otherwise.)

In the last scene of Call Me by Your Name, Elio sits in front of a fireplace and cries contemplatively after finding out that his lover Oliver has gotten married to a woman. The scene shows, maybe, a young person accepting the terms of this sadness, making peace with the inevitable ache of lost love. Sufjan’s “Visions of Gideon” swells alongside the sound of a table being set behind Elio. He cries for nearly three minutes until his mother calls him, pulling him out of his trance, and the song ends.

Even if Elio isn’t exactly listening to a Sufjan song, watching a young person cry silently, resigned, while a Sufjan song plays is such a teenage moment, one that a lot of (sensitive) teenagers have likely had in their own lives, while actually listening to a Sufjan song. Even in adulthood, Sufjan manages to connect with those most basic feelings that we (especially men) tend to lose touch with as we age: Feeling love deeply, mourning loss, and wallowing in those feelings because they’re worth experiencing and talking about. Sufjan validates having feelings, any feelings, even when they’re ugly or traumatic or painful. Isn’t it a relief, for once, to feel our feelings and have a precious, twee baby hold our hand through it all? ●