Everlane, like many retailers, is holding a big sale right now to get rid of excess merchandise, from shoes to sweaters. But in a twist, the online-only clothier is letting consumers pick from one of three prices on each item, betting that some people won't go for the lowest one.

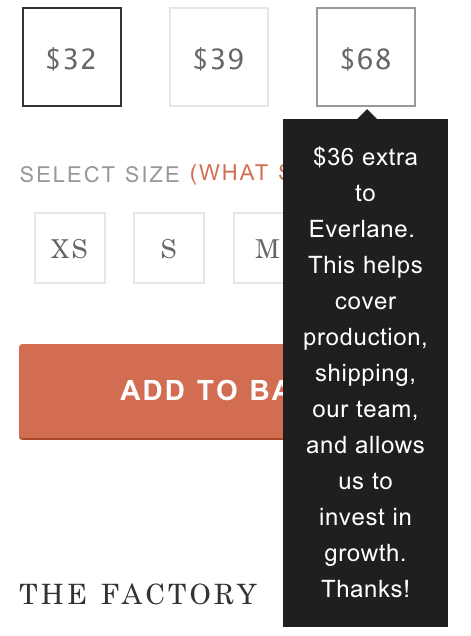

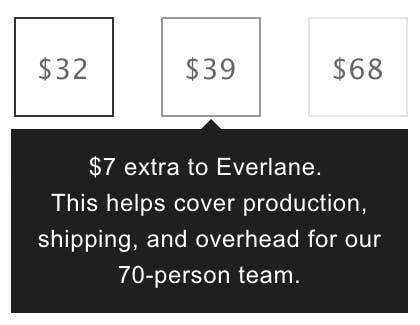

Each item that's part of the "Choose Your Price" sale displays three discounted prices. On a $75 sweater, for example, the discounted prices are $32, $39, or $68. The cheapest price covers Everlane's production and shipping costs, while the second goes a step further, covering that plus "overhead for our 70-person team." The highest price, which is only $7 less than the sweater's original price, includes all of that and also allows Everlane to "invest in growth." ("Thanks!" the description adds.)

Everlane founder and CEO Michael Preysman told BuzzFeed News that the sale drew inspiration from Radiohead and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Radiohead, in 2007, successfully allowed fans to pay whatever they wanted to download its new album, while the Met technically only charges a "recommended" admission fee that people tend to pay.

"We've literally never put anything on the site on sale," said Preysman, who launched Everlane four years ago. "Everlane's obviously for profit, so for most people, we were trying to explain how sales work and how we think about them, and maybe for those with a stronger affinity, they may have wanted to contribute in a way beyond that."

The promotion began this weekend and will run through Thursday, Dec. 31.

This reporter was skeptical of how many people would choose to pay something other than the lowest price. After all, consumers are value-hungry these days — and paying the highest price doesn't give you anything tangible. Like, you know, a keychain, or a pin, or a future discount.

But Preysman said that in a small test of existing customers about a week ago, roughly 10% of people chose either the middle or highest price points.

"If I had to guess, because we haven't selected it this way, they might have bought two things at the lowest price and one thing at a mid-price," he said.

Preysman said he was more involved than he would normally be in the promotion's presentation and limiting the sale prices to three distinct choices. The company also considered making it a "name your price" sale, but that got too confusing, he says.

"There's quite a bit of psychology on how you explain this, and how people click through on it," he said. "We tried to simplify the concept as much as possible."

As for why someone would pay more than the lowest price, he said: "It's the affinity ... If you're honest and transparent with people, then they'll sort of treat you with decency in return."

Preysman said even if 100% of people choose the lowest price, the sale is still worth it, because it's a chance to explain how the company's cost structure works.

That makes sense, given Everlane's entire brand is built on the idea of "radical transparency" — its tagline — and showing customers information about its factories and how it marks up its goods. This was the first year the company dramatically expanded its style count, especially with shoes and jackets, and it plans to add 200 to 250 new styles in 2016. (Preysman argues that's not tremendous, considering some fast-fashion companies introduce 750 styles in a single month.)

"We figured in two years, we accumulated enough in old styles to say let's clear out some of it," he said. "Part of it was this opportunity to explain to the customer what the markup meant, and then the opportunity to give the customer a choice."

The company doesn't plan on holding sales regularly, with Preysman noting this could become an annual event, or held once every two years. Once the sale ends, the items will go back to their regular price, he said.

"We're really focused on making sure people understand this is inventory we need to sell through, not a means to drive revenue," Preysman added.

The goods on sale "were still selling, it was just going to take a really long time," he said. "This helped us clear out a bunch of it, and then we'll put it back at full-price and it'll continue to sell."