We lived in a bubble on a crater on a mountain on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, but where we imagined we lived was Mars. The top of Mauna Loa in Hawaii was the closest place on earth to that distant red planet so that was where we moved through a domed world with airlocks and decontamination zones and wore space suits whenever we went outside. I was just the chef, there to provide nourishment to the astronauts-in-training. A glorified cafeteria lady.

A few miles below were thousands of families who had hauled their winterpale bodies across the sea and stripped down to bathing suits, their skin shy and prickly in the first waves. These vacationers ordered the umbrella drink, ate the papaya, flayed themselves out on the beach and joyfully let the sun burn them.

That was not my Hawaii. I cooked the meals and looked out at the horizon and imagined that I was a year’s journey from my own planet, two hundred and forty nine million miles from everything I knew. That the only lives were those of my crewmates. That what we had to eat, our water, our habitat, was the only place left to us. That we would die here.

The rest of my crewmates were astronauts-in-training. They had entered and won a contest to be the first people to live on Mars. They were young and could run forty miles and had science degrees and high IQs and good temperament and in interview after interview they had each expressed their willingness to give up all the pleasures of earth to die in outer space. Theirs was a one-way mission. If they made it to Mars at all, and they might well not, they would live the rest of their days on a planet inhospitable to human life. They would have to hope that the food that scientists believed would grow on Mars really did grown on Mars. They would have to hope that nothing went wrong with the water supply. They would be radiated by a too-close sun and there would be no hospital to treat their cancers.

Theirs would be names children would memorize in school. John, who had run in the Olympics, Marcy, who had been to MIT, Brit, the brilliant immigrant from a war-torn country in Central Africa, Sherman, whose grandfather had been a famous physicist, Jack, an artist who had shown at the Whitney, and Sunshine, who had lived in in the Amazon rainforest canopy for a year studying frogs and who told me late one night after more wine than we were supposed to drink that she had tried to break off her engagement with the person she had loved since she was fourteen when she learned she had been chosen, but he had insisted they get married anyway, that he would be faithful even after she left for the outer reaches of their solar system. She told me that she was looking forward to being alone.

“What about you?” she had asked. “Tell me your story.”

Mine was the most unremarkable story: I was a girl from a tiny town in Minnesota who’d followed the sun to California and now Hawaii. I had just been through an unremarkable divorce with no heroism involved—my ex and I were two earthlings who were no longer good together. “I’m just here to cook,” I had said. “You are the mission, I am the sustenance.”

Did the food make the day’s work possible? Was it heavy in the heart or the gut? That was my job. This freeze-dried broccoli warmed in a pool of fake cheese and pasta. This glass of Tang, the only bright color left.

As it turned out, living in fake space was no less tiring than living on earth.

As it turned out, living in fake space was no less tiring than living on earth. The astronauts were too cheerful, too serious, too invested. They critiqued every single thing I cooked, examined my attempt at an approximation of Kung Pao Chicken and found the texture depressing. “Yes,” I said, “because freeze dried meat is terrible and Kung Pao is not even a real Chinese dish but I’m supposed to give you American comfort.”

Six weeks into a five-month stay and I was already a bad Martian. If I were on the real mission I would be the person who drove her rover into the red dust of a storm and never returned. I would be the first death in the colony.

One night I found Peter, who I had briefly dated in college, on the internet. We typed our lives back and forth. Happy, happy, happy, we both wrote at first. I’m doing great! I’m living a simulated Martian Landscape! My job is to make the least depressing dishes with the most depressing ingredients!

He said: I bought a house and this really soft rug from Iran! My sister is getting married and says hello! Wait, did I ever tell you that I’m gay?!

I said: Yes, love, I think we all knew that, though I hadn’t.

And then the notes began to include more: his mother’s death, my divorce. Finally, he wrote: I wish I had a child. That was the whole letter. One of ten trillion truths. Not, I wish I lived in a nicer house. I wish my father was alive. I wish my neighbors upstairs would stop rocking in their rocking chairs. I wish for a vacation. I wish I had a child.

It sounded like a project. It sounded like a reason. It sounded like a better escape than the one in which I currently found myself. In the morning, I found another note: I’m coming to Hawaii for a few days. I’ll wave up at the mountain at you.

I looked out the porthole shaped window at Sunshine in her space suit, kneeling in the dust of a perfectly good planet, spooning samples into a vial. I thought of the dozens of pounds of dried cheese I was supposed to turn into sustenance and the weeks ahead of me in my tiny bunk with these other lives as they prepared to hurtle themselves into space and I prepared for the continuation of my plain life. Before noon, I had done the calculations and figured out I would be ovulating on about day four of Peter’s visit.

It was as simple a task as I had ever completed—I served the bad dinner I had made and then I walked out through the airlocked doors, not wearing a space suit. I heard John yell out to me, “What the fuck are you doing?” and I called back, “Problem solve, Astronaut John!” I went past the failing plant nursery, past the lab dome and down the mountain. It was night and cold and I hadn’t been outside without a space suit in six weeks. The air, the earth air, was unspeakably good. It got warmer as I descended and the foliage changed until it was green and lush, and everything smelled like flowers and I stopped to pick a mango off a tree and peeled it with my teeth and ate it, the juice covering my hands and face. This planet, I thought. Holy shit, this planet.

Peter said, “I know we’re in Hawaii and I should take you to some luau but I’m really craving German food. Do you mind?”

“I will eat anything that doesn’t come out of a package. Anything.” We ate schnitzel and dumplings, good pickles. I looked at Peter through the amber and bubble-columned beer. He was handsome through it, warm. The distortion did a good thing to his face. I felt amped up, like I had escaped prison and someone was going to come and drag me back and I had to enjoy every second of freedom.

Peter said, “Do you remember in college when you and that red-head stole a groundskeeping golf cart and ran it into the ditch?” These were the exact stories I wished to forget. Hilarious in the dining-hall morning, funny in the afternoon, but by evening all that was left were two girls with bruises on their shins, the silty residue of a hangover and a lot of homework left undone.

I said, “I forgot how pretty your eyes are.”

“Thanks, kiddo,” he told me.

There was fresh whipped cream on the apple strudel and I ate the whole dollop without offering to share. I thought of those poor jerks on the mountain who were willfully walking away from everything beautiful around them. There were so many miraculous far-aways on this planet and yet they couldn’t find enough to keep them here.

Peter said, “Weren’t you married?”

I thought of those poor jerks on the mountain who were willfully walking away from everything beautiful around them.

I told him that the marriage had felt like carpentry, like sawdust and measuring and labor. My husband and I had tried at marriage every day—we had tried to keep open channels of communication and to show gratitude and give each other space to grow, all the things the internet told us to do. Every time the idea of babies had come up he had said, “Later? I’m don’t feel like a father yet.” I told Peter how, after eight years, I had come home after work covered in kitchen grime and gotten into the shower. It was late. The water was too hot and I wanted it that way. My husband had walked into the room in his boxers and said, “The problem isn’t that I don’t feel like a father, but that I don’t want you to be the mother.” I had looked at him through the glass door and the steam and he looked like a kid. “I wanted to think it was a matter of time,” he had said. I had understood what he meant. There was no blow out. I had been too sad to be angry. He had taken his shorts off and gotten into the shower with me and we had stood there and looked at each other. We had known each other for our whole adult lives. We washed each other’s backs and got out and in the morning we began to search for two new lives.

I looked at Peter and said, “I think I am ovulating and I think we should try to have a baby.”

“Oh,” he said. I knew I wasn’t his ideal mate and maybe I wasn’t his ideal womb either.

But Peter invited me up to his hotel room, as much question in his voice as answer. I inspected the toiletries bag in the bathroom, found it well stocked: expensive shaving cream, Band-Aids, Neosporin, arnica, a small bottle of white homeopathtic pellets that said they treated hay fever. I ate three, letting them dissolve under my tongue. Back in the room the view was huge, the blue ocean and a streak of white beach and nothing else. I still felt like a space-person, exploring this expansive planet, a place with big marble bathrooms and deep soaking tubs and so much water.

Peter took out his phone showed me a photo of him standing on top of a very tall mountain wearing those terrible zipper pants and those terrible wraparound sunglasses. He said, “I’m in good shape, see? I’m financially solvent. I’ll be a really good dad. Are you serious that you’d do this for me?”

“It’s not a gift,” I said. “We’ll share it. The baby, I mean.” He looked unsure. “Not like together. You don’t have to pretend to like this,” I said, gesturing to my body. “We are a results oriented operation.” Then he neck-kissed me. This kiss was soft. The word that came to my mind was credible.

Sometimes I experience sex as something with its own geography, like a hike. This part is piney and the ground is brittle, now we come to a wildflower valley. This time it was just an act. We did only the necessary part and he kept his eyes closed and it didn’t last long. After, lying side-by-side with a bowl of cold grapes, I imagined my body filled with those little swimmers, fast and strong, and the shimmering planet of the egg.

I thought about my ex-husband. There were noises associated with him: arguments and laughter, the moving of furniture. There was silence associated with him, too: breakfast without conversation, the two of us on the couch, the television on mute. The silence I found myself in now was entirely different.

In the morning I sent an email to Sunshine to apologize. I had probably screwed up the whole operation. Someone had to cook, make notes about recipes that worked and those that didn’t. I imagined her sitting on her bunk on Mauna Loa, the photo of her and her sister standing on the beach with the Pacific behind them. I imagined her walking between airlocks to dinner where a plate of Kung Pao Chicken awaited her, fake upon fake, a fiction inside a fiction. I imagined that it made her happy instead of sad. I imagined that for her, it was all worth it.

Sunshine wrote, It’s a real fucking bummer that you took off. I’m giving up everything for this. I’m leaving true love behind. I’ll never have kids. I’ll never be a grandmother. It’s called sacrifice for something bigger, something you obviously don’t understand.

I flew back across the ocean, moved into a new apartment in San Francisco and got work for a caterer cooking decent food with decent ingredients and Peter went back to his life in LA. When I called to tell him about the series of negative pregnancy tests he said, “It takes time. I’m willing to keep trying if you are.” We began our conjugal visits all over California. Each one was two days long and consisted of food and sex only. In Los Angeles we drove east and then came back to his apartment and took our clothes off, the taste of cricket tacos still on our tongues. We got dressed as soon as we were finished and sat in his living room and drank mint tea and I said, “What makes you want a baby anyway?” and he said, “Can you imagine how it must feel to love someone from the moment they begin to exist? To know that you’ll never not love them?”

In September we ate skewers of solidified pork blood and breadcrumbs. No baby. In October, we ate veal brains and got a room at a fancy hotel in San Francisco. No baby. In November, we went for Sushi at a secret place with no sign. The urchin was hot-orange and slippery. The sushi chef brought another thing, a special thing and we each ate a piece of the pale, fatty fish. It tasted like seawater and butter.

“That is amazing,” Peter said.

“Whale,” the chef smiled, and put his finger to his lips. I got up and walked to the bathroom, imagining an animal a thousand times my size diving silently into the depths. I stood over the sink, wanting to throw up, but I couldn’t make myself do it.

That night we did not try to make any babies. Peter slept with his arm over me, and even when my hip got sore and I wanted to turn over, I did not.

Each month, one blue line instead of two on the test. Each month I imagined a pinhead of life in my body, the beginnings of a person who could not simply break up with me and dash off to find a replacement. I would be a good mother. I would be generous and interested in all the side-roads of childhood—superheroes and princesses and dinosaurs and bugs and minor weaponry and animal rights. I would mean it, if only someone would join me in my little life.

In June I had an infestation of meal moths in my cupboards. They flew out whenever I opened the doors and I had to throw away all my food. There were little wormy babies in the hot-cereal box. Everything was hatching except my own body.

In July, Sunshine and the rest of the crew emerged from fake Mars. There were television clips and tabloid stories with pictures of them walking out of the dome in their spacesuits, holding hands. As if they had completed something real. Sunshine was squinting. This was just the beginning. The first heroic mission in a series of heroic missions. Other scientists were building the ships and the housing and the greenhouses and the water purification systems but these were the people who hoped to live and die on the red planet. These were our Martians and the television loved them. I wrote Sunshine an email welcoming her home and she wrote back, This is not home. I won’t be home until I get to Mars.

These were the people who hoped to live and die on the red planet.

I went walking that afternoon. Down the street, a teenage couple was sitting cross-legged on the sidewalk, leaning against someone’s garage door, her in striped tights and him in all black. They were playing cards and laughing. I remembered being sixteen and feeling so in love with my friends that it seemed like they would be enough to sustain me for the rest of time. We wanted to be together all the time, six or eight of us, lying on someone’s floor, pointing out shapes in the puckered ceiling as if the expanse above us were as beautiful as the heavens. We used to take showers together, showing off our new grownup bodies like were comparing gifts. We were young and slippery, more beautiful than we had the capacity to appreciate. We soaped each other up, and maybe we even kissed, girl and girl, boy and girl, but the kisses were just brass tokens, not redeemable for real prizes yet. On my street, I kneeled down in front of the teenagers and said, “Stay as long as you can.”

“We’re not trespassing,” the boy says. “This is public property.”

I walked away fast, turned at the first chance I got. The street was lined with jacarandas, bare branches haloed in the purple fog of flowers.

It seemed like I might never get pregnant and I knew that I would lose Peter, too, if our project came to an end. I revived my online dating profile. I chatted with a guy named Todd. Poor Todd. He never did anything wrong, was probably a good man with bad taste in clothes. We went for pasta and I hated him before he opened his mouth.

I said, “Let’s say you were going to run away, where would you go?”

He thought, hard. “Cancun.”

“Seriously?” At least he hadn’t said Mars.

He looked down at his lap, reddened, said, “Isn’t it supposed to be nice there?” I started naming places: Kyrgyzstan, the Maldives, Siberia, Mozambique, and I could see that Todd’s atlas was not coming into focus. “Wouldn’t you want to go somewhere really, really far away?”

“Maybe for a week. But I like my life here. I have a nice house. I have a gym membership.”

I didn’t know where I would like my life. “Half of me wants to follow a handsome sheep herder across a mountain range, and half of me never wants to leave my apartment. You would be happy with a good tan and a bad tattoo.”

“I hate tattoos,” he said. “So you’re wrong about all of it. You are a very sad person.”

In July, a newspaper clipping arrived in the mail with a note from Peter. What if? he wrote. The story was about a clinic in India where they take your eggs and sperm, mix them and then implant them into the uterus of an Indian woman who carries the child until term when you get on a flight and go pick up your baby. The women live together in a big house, all pregnant with blond-blue-eyed babies while their own husbands and children wait in their own villages for the women to give birth and come home a little heavier and a little richer. I had two thoughts, which arrived at the exact same instant: This is not OK and, We will do this. I called Peter immediately. “Let’s,” I said. “I want to.”

“I didn’t think you’d be into it,” he said.

“I’m into it. I am going extinct.” This made him laugh.

“It’s nice to hear your voice,” he told me, and I had to sit down.

There were phone calls across the seas. The doctor spoke perfect English with a soft British accent. She was soothing to talk to, someone who saw good outcomes from bad situations all the time. I was sure that her office was filled with the photos of new babies, the proof that science had outfoxed the imperfect human body. The first job was to choose a surrogate. The clinic emailed three photographs of smiling young women, one wearing a red sari, one wearing a green Indian top and other wearing a pale yellow t-shirt with a picture of a teddy bear that read Bear in the Dreaming, Dreaming Bear. Peter and I, on the phone, said, “We have to choose her.”

Loneliness had worked its way into my fibers and altered me and now I was about to start timing my menstrual cycle with a woman on the other side of the globe.

I woke up in the night with the feeling that I was floating above myself. Not like an angel, but like a scientist, studying the strange specimen below. I used to be a perfectly normal woman and before that a perfectly normal girl. My life had been unremarkable. When friends of mine had started blogs, I had tried to think of even one thing I could write about my existence. But loneliness had worked its way into my fibers and altered me and now I was about to start timing my menstrual cycle with a woman on the other side of the globe. In two months I would fly to India with a man who I loved in terms I could not explain and get a room in the only hotel with air conditioning. We would go to the clinic where I would be given more hormone injections so that my ovaries bloomed with eggs and he would be given a magazine filled with naked women—Indian or American, I wondered?—but take from his bag one he had brought himself of naked men, and leave his specimen in the little cup. In a Petri dish, our futures would be hitched up like a square-knot, a bind that was microscopic and yet so tremendous that it would tie us together for the rest of our lives. Outside my window, the sun was just a hint in the sky. If I wanted a baby, there was a planet of white-coated scientists together with the lush, young wombs of poorer women. All I had to do was travel there.

Peter called to say that he had to come to San Francisco to see his dying grandmother.

“You can say no,” he told me, “but I was thinking of asking a favor.” I wished the silence on the phone was cracklier, more animated. “She has Alzheimer’s. She does not remember what has or has not happened.”

“OK?”

“Would you be my wife for the day? Would you pretend that?”

I touched my ring finger and I could almost feel Peter slide a gold band onto it, the loop that meant forever.

Peter’s hair was longer than when I had seen him last. He looked younger, more like the boy I had made out with in college. We half-hugged. “Thanks for doing this,” he said and handed me a red gummy bear.

In the car, we made up the story of our marriage. We said that had never broken up after college. “Have we lived in LA the whole time?” he asked.

“No, we spent a year teaching English in Poland,” I told him. “And we saved money and then traveled across Siberia. By train. In winter.”

“Yes. And we spent a few nights in a hotel that was painted pink and did nothing but eat potatoes and drink vodka. No one spoke English except one couple we met at the bar. He was an arm-wrestling coach and she was a math teacher.” I laughed.

“Oh, yeah. Vlade and Natasha. They had four kids, but she was still super hot.”

“But then my mom died, so we came home.” Both of us were silent. I had met Peter’s mother in real life, in college. I really had sat at her kitchen table and eaten a salad just picked from the garden. Peter and I had broken up the next year, and no one goes to visit their briefly-boyfriend’s parents. Good people, people you truly like, get shelved that way. You inherit them for a while, but they are not yours.

“Your mom was lovely,” I said.

“I wish you had been at the funeral.”

“Really?” I asked.

So that was what it came to — you live almost a hundred years and the only things left to report are your name and your disorder.

“You were the only college friend who met her. The older I get the harder it is to remember her like she was real. She’s gotten foggy. It’s like I’m losing her again.”

“If we have a baby, your mother will be part of him or her. I bet you’ll be able to see her.”

Peter opened his window. “This fog,” he said, “it feels like being rinsed off.”

At the nursing home he took my hand and we walked down the hallway, fake-husband and fake-wife, there to offer comfort to an old woman who would remember whatever we told her, and then forget it again the moment we turned around to go.

The tag by the door read Lilian Drier, 92, Dementia. So that was what it came to—you live almost a hundred years and the only things left to report are your name and your disorder. Inside, Lilian was brightly lit, her cheeks flushed as if she had just come in from a winter wind. “Hi Grandma,” Peter said. He kissed her on both her cheeks. She looked past him to me with all the recognition of someone who has come home after a long absence. “Sweetheart,” she said to me, “come here to me.”

At Gate 23, passengers waited to go to Beirut. They pulled gummy candies out of their leather handbags, adjusted expensive-looking glasses, spread a wool throw over the sleeping baby. A group of thin men punctuated their words with flicks of unlit cigarettes.

My gate smelled foreign. The Indian men had colorful shirts and grey polyester pants. Body odor rode the air like a surfer. An American family passed in safari clothes.

Peter’s flight from LA was delayed and I felt half crazy, alone in this airport on my way to sew the seed of my baby in another woman’s body.

I put my head back, listened to a jet engine roar, listened to the final boarding call for Beirut. Here we all were together, all these strangers waiting. By morning, we would be on every corner of the globe. Waking up to cappuccino, chai. I thought of the blonde family opening their eyes in Nairobi, everyone a little afraid and a little thrilled to be in such a scary sounding city. Their high-end tour operator would serve them breakfast and whisk them away, but they would see Africa out the window. And isn’t that part of the appeal, anyway? Won’t the parents feel proud to be exposing their children to the perils of life below the equator? Shouldn’t it make those children feel more grateful for what they have—the rooms of their own, the air conditioning, the sedan in which everyone gets his or her own booster seat, rather than piling onto a moped with nothing to protect them but a small Jesus charm glinting on the handlebars? It was leaving that made home so sweet.

I looked up at the television to see a breaking story about an explosion at Cape Canaveral. A rocket bound for the International Space Station had burst into flames. The video played on a loop: spark, flames, smoke. I thought of Sunshine, who I assumed was back home in Florida, completing each stage of her training — medical or spaceship technology or Mars geography — until she could finally, victoriously, leave her own planet for good. The first unmanned rocket with supplies for a habitable settlement on Mars was scheduled for two years out. The first crew was supposed to leave in four. Sunshine would be thirty. I thought of that fixed point, the countdown, the launch, and everything that could change before then. The loves that would be loved or abandoned, the body’s secrets — illness, desire — come to light. I thought of the stores of freeze-dried sustenance. The explosion was repeated again on the television screen and the pink-lipped newscaster looked grave.

I saw Peter before he saw me. He walked down the long hallway, a coffee in his hand, looking almost peaceful. He was whatever he was to me—my gay ex, my friend, the father of my dreamchild. “Hey, Mama,” he said when he got close. He patted my belly. “Feeling anything kick?”

“Not funny,” I said. But no matter. So much was possible. Here we were, on our way to a life of meaning.

“Are you ready?” Peter asked.

We two made no sense, but no one else made sense, either.

A fat white guy in cream-colored linen suit sat down in front of us and answered his loudly ringing phone. “Yes,” he said, almost shouting. “Andy, it’s the best, the very best, you can get.” Everyone at the gate stared at him. He looked not at Peter and me but through us, like we were an incidental geographic feature on his horizon. “Andy, Andy, Andy,” he said at high volume, “the chrono-layers are socketed. The entire motherboard has astro-filament. It’s the most advanced technology to date. With this in your hands you can do anything. It’s a fucking super-power.”

Peter looked at the fat guy and then at me and we laughed. We two made no sense, but no one else made sense, either.

Our plane pulled into the gate, its fuselage winked in the sun. The rocket exploded again on television.

“I’m ready,” I said.

Suddenly the fat guy looked right at me. He winked. “Baby,” he said into the phone, his eyes fixed on me, “Baby, baby, baby. Trust me. You’ll never lose a fucking signal again.” ●

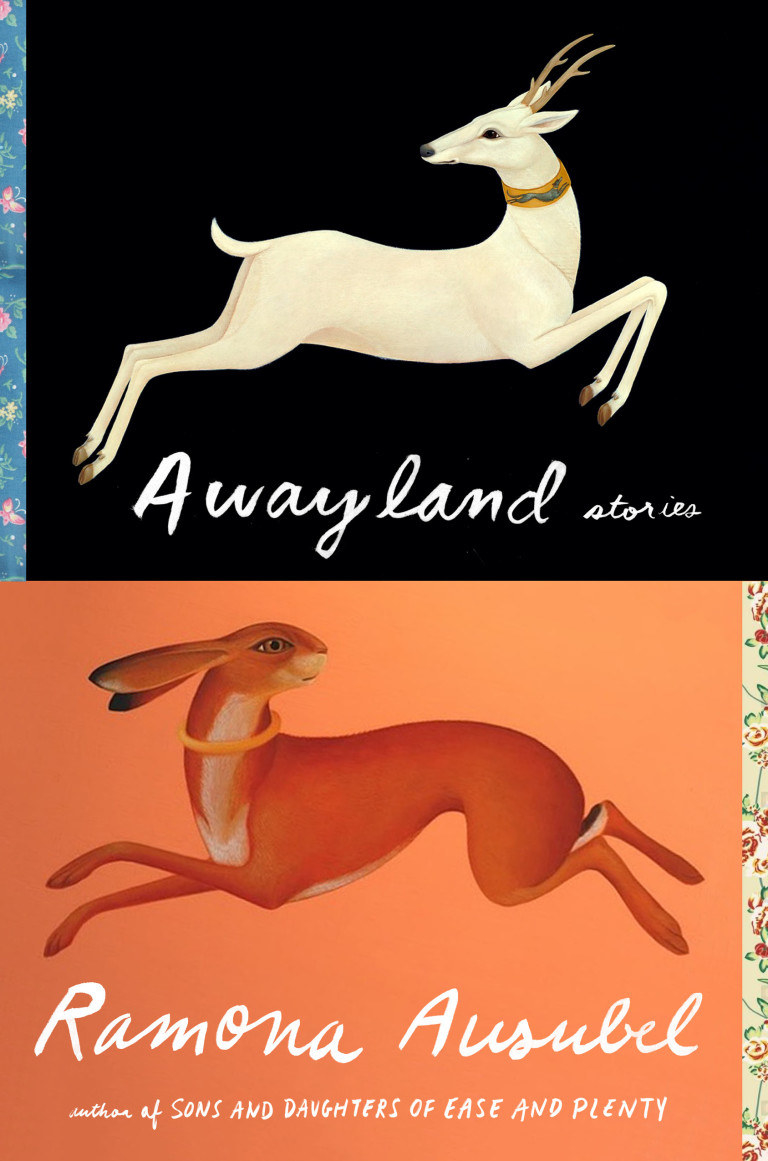

Illustrations by Léonard Dupond for BuzzFeed News.

Ramona Ausubel is the author of Awayland, publishing March 6 from Riverhead, and the novels Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty and No One Is Here Except All of Us, winner of the PEN Center USA Fiction Award and the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award, and finalist for the New York Public Library's Young Lions Fiction Award. She is also the author of the story collection A Guide to Being Born, and has been published in The New Yorker, One Story, The Paris Review Daily, and Best American Fantasy.

To learn more about Awayland, click here.