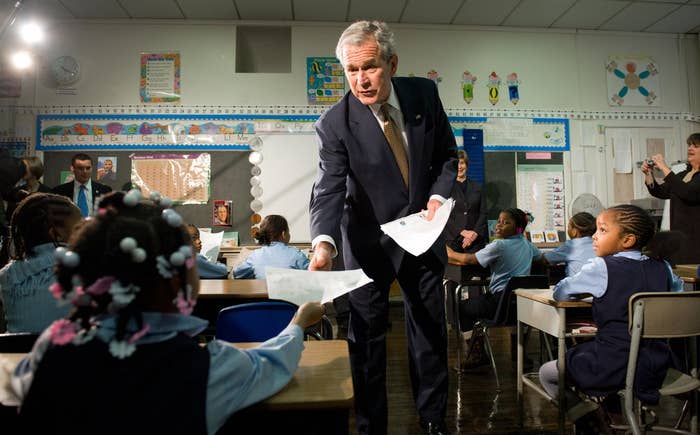

At the center of what is gearing up to be the biggest political battle over American education in decades, leaders across the political spectrum are calling loudly for the end of the test as we know it. Standardized testing was shaped by George W. Bush's No Child Left Behind Act into a central pillar of the American education system — a federal mandate on which the fate of low-performing schools rested.

But the 13-year-old No Child Left Behind is in the process of being dismantled, and lawmakers' first priority is to to change the standardized testing regime. They plan to remove many of the high stakes attached to tests, slash the number of exams students must take each year, and even, under some proposals, eliminate No Child Left Behind's central mandate, that students must be tested every year.

But the testing industry — a multibillion-dollar market built, in large part, on the shoulders of No Child Left Behind — isn't worried.

Thirteen years after the law was enacted, widespread testing is so ingrained in the American education system the companies who profit from it see little threat from plans to remake elementary assessment. No matter what the federal government decides, experts say, states are likely to keep annual testing around in some form or another, likely with high stakes attached to them.

For the companies that rule the testing world — Pearson, which has a 40% market share in the industry, McGraw-Hill, and a handful of large nonprofits — No Child Left Behind is already an afterthought. They are riding the high of the huge revenue boost created by implementation of the Common Core standards, and expect demand to increase in 2015 as states and school districts look to develop new and innovative types of assessments and tools to analyze their students' results.

Some experts said they even saw potential for the testing industry to see a boost from a new version of No Child Left Behind.

"I don't see things changing for us much in terms of the size of our business," said John Oswald, the vice president of Educational Testing Service, a large nonprofit test maker. With No Child Left Behind's mandates over, Oswald said, "People are just going to be moving towards other kinds of testing."

In 2002, when it was signed into law by George W. Bush, No Child Left Behind was unarguably a boon for testing companies. The law required new, different tests, and lots of them: enough for students to take a test every year from grades three through eight, and once in high school. The federal government pumped tens of millions of dollars into each state's budget — from 2002 to 2008, annual state spending on tests rose from $423 million to $1.1 billion, according to the Pew Center on the States.

The money was used to develop a battery of data-rich tests that would be used to measure how many students in each grade were "proficient" in reading and math. Unlike in the years before No Child Left Behind, those tests suddenly carried consequences: Schools were graded based on whether they brought enough students up to proficiency each year, and could face increasingly dire consequences if they did not, including possibly being shut down.

A new version of No Child Left Behind would almost certainly remove the federal sanctions that made NCLB's tests high-stakes for schools, which some see as a potential threat to large education and testing companies like Pearson and McGraw-Hill.

Lily Eskelsen García, the president of the National Education Association, the country's largest teachers union, said that education companies have long relied on the threats posed to schools that fail tests in order to sell test-aligned curriculum and test-prep materials.

"As the consequences and punishments go up, the profits have gone up astronomically," said García, who is a prominent critic of the industry and of NCLB-style testing. "Schools are frightened of failing. And then a salesman walks into the district and plunks down their products, saying, 'Here's how we can keep you off the failure list.' ... It's a perfect business model."

Scott Marion, an associate director at the Center for Assessment, agreed this could be a danger for McGraw-Hill and Pearson, which sell educational materials alongside their tests. "If [districts] don't feel as much pressure, they may not be as compelled to buy materials," Marion said. "That's definitely a threat. And it could be a good threat — getting rid of test-prep materials would be a great thing for student learning."

But the high-stakes nature of testing is likely to remain in some form, said Marion. "A lot of people point solely at NCLB, but states drive accountability now more than the feds," said Marion. "State legislatures have some pretty tough provisions" for schools that don't succeed on tests.

Experts say that the testing industry sees its future in the Common Core, which began to take hold nationwide in 2011. Adoption of the stringent standards, which are being used by 43 states, necessitated designing new and different types of testing in addition to NCLB exams. Common Core tests function differently than NCLB tests, measuring students against standards of college and career readiness rather than NCLB-era "proficiency." Common Core tests are also designed to measure higher levels of thinking, proponents say.

In the years after the Common Core was widely adopted, the testing industry saw a boom that rivaled that of NCLB: The industry grew 57% from 2010 to 2012, according to the Software and Information Industry Association, a trade group. It now has annual sales of more than $2.5 billion.

As part of the remaking of No Child Left Behind, many lawmakers — even those who want to keep mandatory annual testing — are looking to reduce the number of tests students take each year, saying too much classroom time is devoted to test-taking and test preparation. Even that is unlikely to have much impact on the industry, Oswald said. Revenue from testing is broken into two categories: money that comes from administering tests, and money that comes from creating new ones.

While administrative dollars might drop, Oswald said he expects the demand from states to create new tests to stay the same — and perhaps even increase. Right now, most states that administer Common Core tests use assessments developed by a large group of states, called a consortium. But a recent trend — fueled by growing anti-Common Core sentiment — of states leaving those Common Core testing groups to develop their own exams is likely to mean more contracts and revenue for the testing industry.

That is a trend that could gain traction under a new draft version of No Child Left Behind proposed by ranking Senate Republican Lamar Alexander. Alexander's draft is all about giving power to states rather than the federal government, which will likely mean more states breaking out and developing their own tests — good news for testing companies.

"States may be allowed to do some different things with testing and accountability. That kind of diversity of marketplace is kind of good for creative and thoughtful companies," Marion said.

There is also increasing demand for so-called "formative" assessments, which are informal tests used by teachers at different points in the year to monitor progress. McGraw-Hill, whose testing arm is second only to Pearson among for-profit companies, has invested in these kinds of tests, as well as in technology and data analytics that allow on-the-go assessment of student performance. Traditional standardized testing has become an increasingly small part of McGraw-Hill's business, said Jeff Livingston, who heads education policy for the company, instead replaced by more creative types of assessment.

McGraw-Hill is betting that the next time Congress considers an elementary education act, traditional testing will be a thing of the past. "The notion of having to stop class and give a state exam will be ridiculous," Livingston said. "There will be so much info available digitally in real time that teachers will always have a sense of where the student is as they're interacting with lessons."