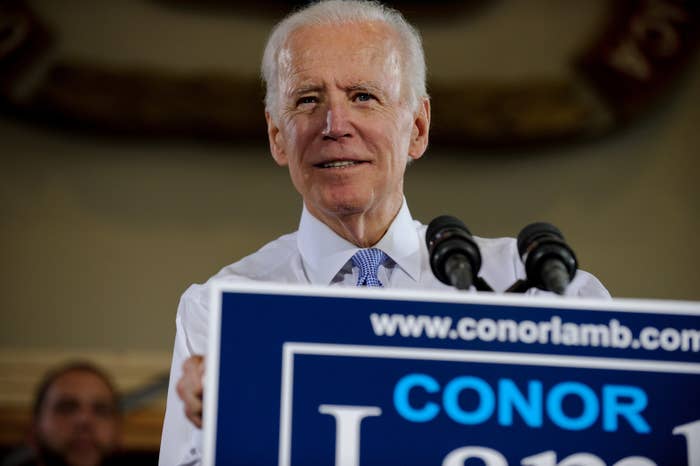

Joe Biden hasn’t decided whether he’s running for president, but he has assembled a coalition of 30 of some of the biggest names in Washington last month to help shape his domestic policy, from union presidents to former top Obama administration officials to bank officials.

Announced last month, the Biden Institute’s new Policy Advisory Board is the next major piece in what is shaping up to look like a very familiar playbook: a potential presidential run rooted in old-school, establishment politics, capitalizing on his broad popularity among Americans and vast experience in politics. It’s also a sign of what might be a weakness for Biden in a potential primary.

People close to Biden maintain he has made no decisions about whether to challenge Trump in 2020. But the work he is doing now, they say, is with a goal of keeping options open in the event of a presidential run. Said one former Biden adviser, “He’s building out a host of different pieces, and he’s definitely doing that with an eye towards the presidency and the future.”

Though many of Policy Advisory Board members say joining doesn’t mean they’re signing on to support him if he runs for president, the adviser said, “They have to know what they’re doing to some extent. It doesn’t lock them to him, but it certainly encourages them to stay close to him.”

The list of names, with the occasional exception, offers a glimpse of the people that would be likely to orient themselves around Biden in the event of a run: corporate leaders, union bosses, and longtime Obama allies.

There’s senior Obama adviser David Plouffe; former acting attorney general Sally Yates; top executives at Edelman, JPMorgan Chase, and Morgan Stanley; and the presidents of the Service Employees International Union, the United Farm Workers, and the International Association of Firefighters. There is also Steve Schmidt, a prominent Republican campaign strategist, and former hedge fund boss Eric Mindich.

In a sign of what Biden might face in a presidential primary, though, some progressives see Biden’s advisers as a sign of a candidate that is too centrist, closely tied to corporate and party interests.

“I think this is a missed opportunity for the former vice president, particularly if he’s thinking of running,” said Jim Dean, the chair of Democracy for America, a progressive PAC, of the advisory board. “Most of these folks have corporate-driven missions — they’re funded by big business. The folks that really need to be on a panel like this right now are people that you and I have not heard of that are living the reality that most Americans live on.”

More than a half-dozen members sidestepped questions from BuzzFeed News about whether they wanted the former vice president to run in 2020. Asked if SEIU president Mary Kay Henry had joined in part because she thinks Biden should consider a run, a spokesperson said she joined because Biden was "a leader in how we develop and implement public policies that ensure the dignity of all working people."

Many cited long-standing personal commitments to Biden and a belief that, on the issue of the economy and working-class jobs, he speaks uniquely to the kinds of voters that the Democratic Party lost to Trump in 2016.

“The first reason I joined is out of personal loyalty to Biden,” said Larry Summers, a top Obama economic adviser and the former president of Harvard. “The second reason I did it was I think that he’s very focused on what I think is probably the central economic issue for the future of our country — which is improving the lives of working people.”

If he does run, Biden will also likely face some sharp critiques of his 1990s record, from his past role in the 1995 crime bill and the Anita Hill hearings, to his relative political centrism. At a time when the political forces favor opposition, Biden likes to talk about compromise.

Dean, of Democracy for America, said Biden’s advisers were unlikely to consider how closely the former vice president’s economic concerns were tied to issues of racial justice.

Biden “comes from working-class roots, and we don’t question that, but times are not the same as when he was going through them,” Dean said. “There’s a racial lens to this that wasn’t as present during the vice president’s time growing up in Scranton.”

Sarah Bianchi, the board’s chair and a longtime Biden ally, said the group planned to begin by tackling civil rights issues, adding that "racial economic justice was discussed at length in the initial meeting."

In the year and a half Biden has been out of office, he’s created a network of initiatives that play to his probable strengths: the Penn-Biden Center, which studies foreign policy and diplomacy, including a growing interest in trade issues and problems of globalization, on which Biden has been vocal. There’s the “cancer moonshot,” the Biden Cancer Initiative, which was born out of Biden’s wrenching personal history with his son’s death from cancer in 2015, and the Biden Foundation, which focuses on the social issues he’s kept close — namely gay rights and violence against women.

At the Foundation, those issues have their own new advisory boards too, stocked with activists and names like Cyndi Lauper and Judy Shepard, Matthew Shepard's mother.

There’s also Biden's book, Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose; the next leg of his drawn-out book tour, in May, is taking him to many of the red states where people have speculated Democrats have a chance of overperforming in 2018 and beyond — Georgia and Tennessee, as well as North Carolina.

The Biden Institute, at the University of Delaware, does domestic policy work — particularly the economic issues that are Biden’s bread and butter. But it will also tackle things like criminal justice and environmental issues, said Bianchi.

The Institute’s advisory board is stocked with longtime Biden loyalists, like the president of the powerful International Association of Firefighters, Harold Schaitberger. The IAFF threw itself in support of a Biden run in 2015, before he had made any formal announcements. When he said he would not run, the union waited months to support Clinton.

This time, Schaitberger said, the situation is much the same. “I wouldn’t want to get in front of my membership or my leadership, but if Joe Biden decided to offer himself up in service to the country, we’d be hard-pressed not to support him,” he said.

But most declined to even allude to supporting Biden if he ran. “I haven’t picked a horse yet,” said Deepak Gupta, a top attorney and Institute board member who has led cases against the Trump administration. Like just a small number of people in the Democratic Party, he said, Biden “has the ability to speak to working-class Americans in a way that resonates with them.”

Schaitberger and others on the board described a Democratic Party adrift — and Biden as one of the few people who could right it by refocusing the party on economic issues.

“Hopefully we’re going to see the political community getting their voice back and start speaking again to workers, and moving away from some of the identity politics stuff,” Schaitberger said. Biden is “clearly a voice that knows how to speak to workers.”

“I know by January, I have to make that decision,” Biden said in a speech at Vanderbilt University on Tuesday. “If God Almighty himself came down today and said, 'The nomination is yours,' I’d say no. Where I'll be in eight months, I don’t know. In the meantime, I'll do everything I can to be sure we elect a Democratic Congress.”