If you don't already play it, you've seen it — on the subway, in line at the grocery store, or in the elevator. It's a simple, brightly colored, pattern-matching game called Candy Crush Saga, and it's the hottest game on the planet. Tens of millions of people play it on their phones every day, and yet almost none of them could name the company that puts it out.

That would be King.com, a 550-person company that has ridden the explosive popularity of the game to a confidential IPO filing (think: Twitter). A public offering will infuse cash into the already booming company and, potentially, help it grow even faster. What could go wrong?

Well, ask Zynga. In 2009, that company released FarmVille, which also held Candy Crush-level momentum, and two years later helped propel Zynga to one of the largest tech IPOs since Google. But in the intervening four years since Farmville's release, Zynga has seen its value completely collapse from a series of bad decisions that ultimately led to CEO Mark Pincus stepping down. In short, it couldn't find another game to match the success of FarmVille and its follow-up CityVille.

The challenge before King.com is to avoid Zynga's fate in the immediate aftermath of its IPO. (Zynga, to be fair, is currently in the midst of a turnaround.) To do that, it must leverage the popularity of Candy Crush Saga into a stable and growing public company.

It won't be easy — interviews with nearly a dozen insiders, former and current employees at Zynga, industry watchers, and designers reveal that there are still significant questions around King's ability to branch out beyond its superstar game. However, the good news is that King.com has built an organizational infrastructure specifically designed to avoid suffering Zynga's fate — provided they are able to find a future beyond Candy Crush Saga.

King.com's slow rise to prominence

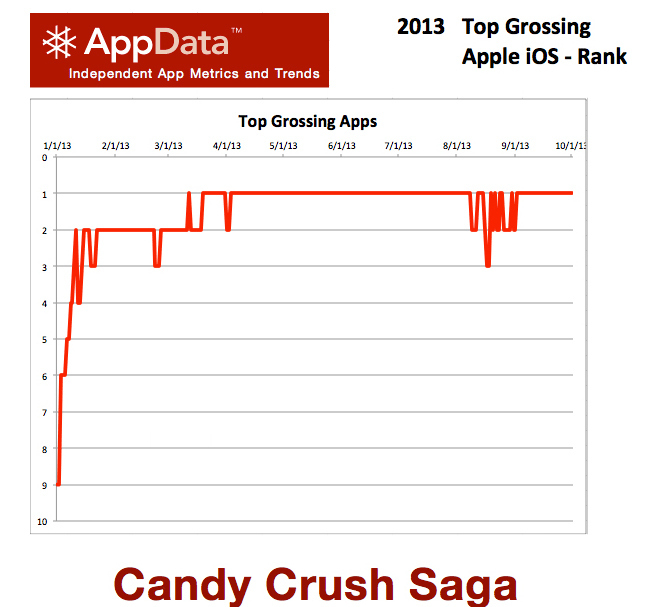

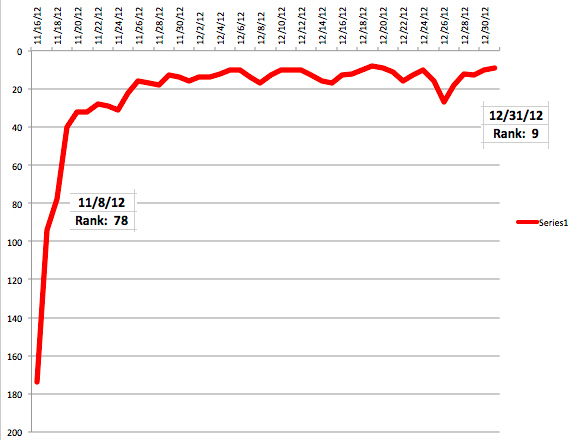

King.com has in fact been around even longer than Zynga. Founded in 2003, the company went largely unrecognized until the launch of Bubble Witch Saga — a bubble-popping game — in September 2011. Candy Crush Saga followed just eight months later, launching first on Facebook in April 2012. Things didn't take off for King.com, however, until it ported the two games to mobile later that year. Now, roughly 100 million people play its games daily, and more than half of those people are playing Candy Crush Saga, according to AppData, a service that tracks apps connected to Facebook. King.com also says Candy Crush Saga sees 700 million plays every single day.

According to Think Gaming, Candy Crush Saga generates revenue of around $850,000 every day in the United States, or about $310 million a year. (at the end of the nine months of 2011 prior to going public, Zynga generated about $828 million, per its SEC filing the day it went public.)

Small wonder then that the company is focused on Candy Crush Saga — with a small part of its 250-person Stockholm team working on it, according to the company's "games guru," Tommy Palm. While the game does not have a "new" concept (its "match three of the same tile" mechanic has been around for years), the company has put much effort into finding ways to differentiate it from other similar games.

That's not to say King.com isn't experimenting. It has several other smaller hits on the App Store like Pet Rescue Saga, Papa Pear Saga and Farm Heroes Saga. The company uses its titular landing page for experimental games that it will push across platforms if they deem them successful. And some of its old hits are still going strong, Palm said.

"For us, right now, we have a lot of games in our portfolio ready and we continue to innovate and experiment on King.com," he said. "It was interesting to see that Bubble Witch, now more than two years after launch, is still a top-15 on the Facebook top charts. The lifespan of the games is significantly longer than they were in the traditional games networks."

King.com is diverging from pre-IPO Zynga already in one area in particular: Asia. While the region has historically frustrated Zynga and other game developers, Palm said King.com plans to focus its attention on Asia in the upcoming year. To be sure, just last month they launched Candy Crush Saga on Kakao, a social network popular in Korea.

Lessons from OMGPOP

If King.com's story sounds familiar, it's because you've probably heard it before. The path Candy Crush Saga is blazing for the company is analogous to Draw Something, the blowout app built by New York-based game company OMGPOP that exploded in popularity before flaming out in spectacular fashion.

Like King.com with Candy Crush Saga, OMGPOP had stumbled into a cultural zeitgeist with Draw Something, which at one point had more than 10 million players logging into the game every single day. Originally, it was a spin-off of Draw My Thing, a game launched on OMGPOP.com and later on Facebook. It wasn't until OMGPOP decided to build a Draw Something mobile app that the game exploded, prompting the company to essentially abandon other game projects and pour its resources into building out the Draw Something network.

The success of Draw Something resulted in buyout offers for OMGPOP from Electronic Arts, Disney, and Zynga, which beat out the others by offering more than $180 million.

Soon after, corporate politicking began erasing everything the team at OMGPOP, led by Dan Porter, had built. Zynga imposed what was described as a hiring freeze and also insisted on localizing the game for other regions, among other corporate mandates, as earlier reported by BuzzFeed.

Around the same time, it also became apparent that people weren't coming back to play Draw Something over and over again, especially over an extended period of time — known in industry parlance as "long-term retention" — in the same way they were with Words WIth Friends or other Zynga games, according to several company insiders. This is usually done with some layer of progression, like a "level-up" system that makes players more powerful the longer they play, or giving players something to master as they play the game in the case of a game like Chess.

Zynga and the OMGPOP team decided the way to solve the retention problem was to create a sequel, but Zynga proper and OMGPOP disagreed on how to address it, according to several people familiar with the plans of the game. Zynga thought the game should be optimized around shorter, more entertaining content, while OMGPOP wanted to give users tools to showcase their art. Internally, however, there wasn't much data to back up whether the Instagram-like art showcase approach would work, according to several people familiar with the game's development.

A series of technical snafus in implementing Zynga's With Friends network slowed the game down, as earlier reported by BuzzFeed. When Draw Something 2 eventually launched, it inevitably proved to have similar problems to its predecessor. The shortfall of Draw Something 2, along with poor financial performance, a swooning stock price, and a host other problems, led to a massive reorganization at Zynga that included shuttering the OMGPOP studio and a massive write-down on the acquisition, laying off more than 500 employees, and Pincus stepping down as CEO.

Within OMGPOP, much of the blame rests on Zynga, and vice versa. Zynga insiders point to issues with the "core loop" of Draw Something — which are valid — and OMGPOP insiders point to the interference of Zynga proper — which is also valid. Several sources said the OMGPOP team attempted to buy back the brand, but Zynga was unwilling to let them do so. It's still not entirely clear which one sunk the ship, or whether it was a mix of both, but for all intents and purposes, OMGPOP is dead.

Why Candy Crush Saga is so addictive

Candy Crush Saga borrows not only from the Draw Something playbook, but also that of World of Warcraft, and carries with it a few innovations on top of the traditional match-3 mechanic.

The game, like many social games today, uses social pressure — utilizing connectivity to networks like Facebook and now Kakao — to build out its reach. Candy Crush Saga players can call out for help and get additional lives by asking their Facebook friends through the game. There is also a progression element that keeps players coming back over and over because there are always more levels to play through — new levels come out every two weeks — which gives the player a sense of gradually moving toward the end goal of mastering the game. It can also be played online or offline. So, whether underground or in the wilderness, there is always an opportunity to play — particularly with a single hand.

"Candy Crush was the first candy-themed game and it had this invention in the fact that you could combine two power-up candies with each other — that changed the core dynamic," Palm said. "A lot of these small details, like super-high frame rate, being able to play the game with just one hand and using just your thumb is really important, so people can hold onto something else while they're playing."

But the game's real art and mastery, according to many game designers BuzzFeed spoke with, is what is described as "sawtooth tuning." Essentially, this is a description for variation in difficulty where easy levels are wedged behind very difficult levels. That helps give players the satisfaction of having a significant accomplishment, along with a sense of progression in their mastery of the game — much in the same way players feel when they master games like chess — as the following levels are often times easier. And at points where victory seems just barely out of reach, players can spend money to purchase those last few bits they need to power through to the next level.

"You've got to have a slow boat to China — if there's no other way to get there you give up on China," one longtime industry veteran said in describing sawtooth tuning. "The brilliance is giving me enough friction that i see the value in buying but not so much that I give up the game."

Avoiding one-hit wonder status

In the early 2000s, Blizzard (now Activision Blizzard) released an online title called World of Warcraft, which at its peak attracted nearly 10 million subscribers paying a monthly subscription fee of $15. Electronic Arts also found itself with a massive surprise hit in the semi-voyeuristic life simulation game The Sims and its sequels, which would go on to become one of the largest-selling franchises of all time.

Fast-forward to today, however, and those two companies find themselves with questions about their businesses. World of Warcraft is beginning to lose users, down to roughly 7.7 million in the most recent quarter from 8.3 million a quarter before — and from a high of around 10 million — without a true follow-up in sight. The CEO of Electronic Arts, John Riccitiello, stepped down amid concerns over the company's ability to innovate in mobile and missteps in the online gaming space with its own comparable World of Warcraft game, Star Wars: The Old Republic.

The lesson here is self evident: For a gaming company to stand the test of time, it has to not only create a breakout hit, but also be able to follow-up with another breakout hit — and then keep them coming. The gaming industry is hits-driven and cyclical, and no one title lasts forever.

For its part, King.com has already shown an ability to make games that, while not quite at the level of Candy Crush Saga, are for all intents and purposes well-performing games, with some featuring more than 10 million monthly active users each, according to Facebook data.

"The thing about King is, it's more than a one-hit wonder," said Michael Pachter, an analyst at Wedbush Securities. "They've had four to five games that have done well — Candy Crush is killing everything, but the other games are about as big as Zynga's big games."

Rovio went through a similar phase as it tried to branch out from its Angry Birds franchise with games like Bad Piggies. It has also tried new styles of games layered on top of the typical Angry Birds title, such as gravity mechanics in Angry Birds Space and its co-oped game Angry Birds Star Wars. Rovio has found ways to expand through merchandising and other forms of media, but it hasn't quite followed up with another Angry Birds-level franchise.

Still, there's an art to finding new hits and not flooding the market with games that players won't find enjoyable — and inevitably getting a bad rap for fast-follows and bad games.

"Our strategy is not to flood the market with super-many different merchandising things or to look at a few designated deals that make sense from a player perspective," Palm said. "We said, focus on things that bring a smile to the face of a player — in core for us it's still the game — and continue to innovate and focus on what the market is looking for right now."

Candy Crush Saga is often compared to two other games coming from rival Swedish studios. The first is Clash of Clans, a game from Finnish developer Supercell, which regularly vies with Candy Crush Saga for the top-grossing app spot. Clash of Clans was reported to be generating around $2.4 million a day in May.

The other game is Minecraft, a massive hit that basically has no comparable historical analogue. It is essentially virtual legos, dropping players into a world built out of a series of blocks that can be deconstructed and rebuilt in whatever way the player sees fit. The company behind Minecraft, Mojang, has sold more than 20 million copies of the game, collecting around $90 million in income off of $235 million in revenue last year.

Together, King.com, Rovio, Supercell, and Mojang are all more than capable of rising to the levels of Zynga, Activision, Blizzard, and Electronic Arts in their heyday. But all of them still have the same burning question: Can they grow beyond their breakout hits? Can they navigate the subtle balance between focusing on their hit game and still find a way to generate that second hit, and ones beyond?

For inspiration, gaming veterans say, they can look to Valve, a traditional gaming company that has become iconic in the industry. Focusing on a small subset of the gaming community, Valve has managed to churn out hit after hit in the form of franchises like Counter Strike, Half Life, and Portal, and has also transcended beyond a simple games company to a true publishing platform through its Steam platform.

But it's worth noting that Zynga's attempts at building its own network, the With Friends network, that spanned its games was not as successful as Valve's. Much of the time was devoted to solving technical problems rather than focusing on user tools like cross-game chat, according to several people familiar with Zynga's plans. Part of that was borne from the engineers, who had to essentially be ready to separate from Facebook in the company's earlier days when the two companies were much more reliant on each other, according to several people familiar with the company's plans.

Though, it may be that building an independent network is no longer even necessary with the emergence of Facebook and other follow-up networks internationally, like Weibo and Kakao, that games can exist within. When asked about making the jump to forming a true independent network, Palm said that for now King.com had nothing to announce.

"Working with Facebook has been really good for us and worked out really well and they've been a really important partner," Palm said. "It's a great tool to create great social functionality, especially in the western world where this is such a big and vibrant network. But we also show that, now with Korea, that we're not completely dependent on Facebook as a social network. We could also integrate it to other social graphs if that makes sense."

And, perhaps, that's the key to King.com avoid a post-Candy Crush crash.