In the fall of 2008, during the height of the financial crisis, raising venture capital to fund your startup amounted to a fool's errand. But PayPal alumnus David Sacks is no fool, and he knew exactly who to tap to get his new messaging service off the ground.

That service was Yammer, and the person Sacks tapped for both money and advice was George Zachary, a partner at early stage venture capital firm Charles River Ventures. In return for its tiny financial investment and strategic advice, CRV was repaid with a handsome profit after Microsoft bought Yammer in 2012 for $1.2 billion.

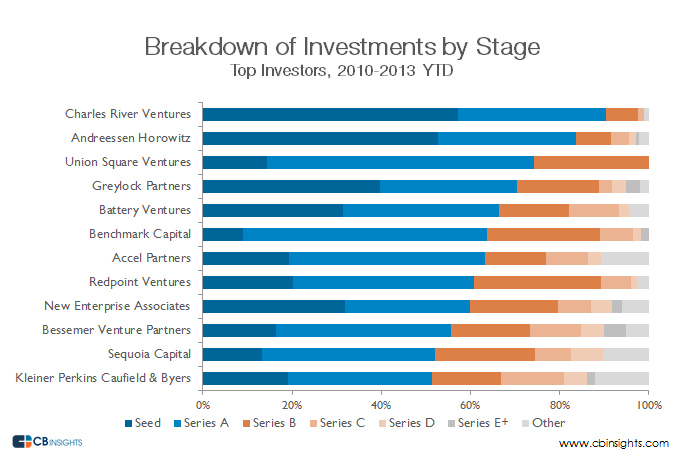

Named after the Charles River in Boston, CRV has quietly emerged as a real force in Silicon Valley on par with better known and more established venture capital firms such as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Bayer or Greylock Partners. The firm, which moved most of its operations to the Valley a decade ago, has strung together a series of high-profile exits to go along with Yammer. In 2003, almost a quarter of their portfolio was west coast-based, and most of the partners were on the east coast — it's now nearly 60%, and most partners are on the west coast.

"The market perception, especially here or in San Francisco, is that we're not there," CRV partner Izhar Armony said of the view of his firm's place among the Valley giants. "But results-wise, we're definitely in that group."

CRV — as the firm is known around Sand Hill Road, the Menlo Park, California expanse that hosts the most powerful venture capital firms in the world — is poised to continue its streak this year, with evidence emerging that its early bet on Zendesk is about to pay off big in the form of a potential IPO of the enterprise software maker. It also recently landed an investment in Pebble, a fast-growing smart watch startup.

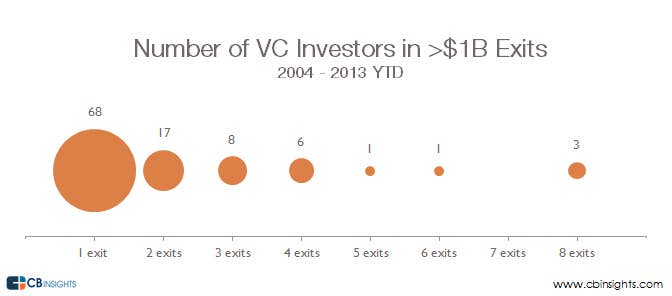

"Unicorn" exits, or sales or IPOs of venture capital-backed companies in excess of $1 billion, are exceedingly rare. According to CB Insights, 68 investors were able to capture at least one billion-dollar exit in the past decade ending November 21, 2013. That number falls to 17 for two exits, and continues to shrink.

Three firms — Sequoia Capital, Greylock Partners, and New Enterprise Associates — were able to score eight "unicorn" exits each (or 24 total) according to that report in the last decade, a phenomenal track record of consistency. Sequoia Capital recently had one of the largest exits in venture capital history after Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19 billion.

CRV is not far behind those firms, though, with "unicorn" exits, included among them Twitter (IPO), Yammer (sale), Millennial Media (IPO), EqualLogic (acquired by Dell for $1.4 billion) and Netezza (acquired by IBM for $1.7 billion). Zendesk will likely up CRV's tally closer to that of Sequoia and Greylock when it eventually goes public.

"Partners are fined $10,000 if they take out their mobile device during pitch presentations."

CRV's partners credit its success in part to its organizational structure, where everyone has an equal say in determining whether the firm invests in a company. Prior to making a decision, the firm forms a "deal team" where a few individuals scope out a space or a company and decide whether to take it to the firm's partners for investment consideration. Presenting to the whole group, if it gets that far, is serious business — partners are fined $10,000 if they take out their mobile device for any reason during pitch presentations. Each member votes on a scale of one to four how confident they are in the investment, with one being least confident and 4 being highly confident. A majority of votes in either the least or most confident category is considered a troubling sign.

"If it's not intuitive at the time, we actually see it as a good sign that we have different opinions and controversy around that," Armony said. "We know that our best investments ever were very controversial. We always had one or two strong advocates, and one or two where they were strongly against."

Back in 2009, for instance, recently hired CRV partner Devdutt Yellurkar hypothesized to Armony that the next generation of enterprise software was going to be more consumer-friendly — a theory that was controversial at the time but has since been basically proven true in practice. He had tracked the progress of Zendesk through conversations on Twitter, and eventually found the phone number of Chief Executive Mikkel Svane in an old conference agenda. After making contact, Yellurkar flew to Copenhagen, Denmark, to gauge the company's interest in an investment. Upon his return, he convinced Armony to get in early on Zendesk.

Armony, at the time, was eyeing another company, according to Yellurkar, but decided on handing the reigns over to Yellurkar and investing in Zendesk.

"Most other firms, because they are hierarchical, the partner would have either said, 'You're crazy', or 'I'll do the deal,'" said Yellurkar. "In CRV it's kind of like, 'If makes sense, go do it,' because the successes are always shared. I was less than 6 months into the company, and one of the lead partners in the firm said he wouldn't do his project because this made sense. Go do it."

CRV, like any early-stage venture capital firm, takes on an enormous amount of risk when investing in a company, and any kind of success is at least a year and a half, if not more, out from the time the investment is done. When CRV makes an investment, it is often betting on the people as much as the idea, so the firm takes its time getting to know a company's founders. Mailbox co-founder Gentry Underwood met with CRV partner Saar Gur several times over a six-month period before the firm finally settled on a $5 million investment in the company. At the time, it was essentially "two guys and an idea," Gur recalls, noting that the first creation of the founders, a to-do list called Orchestra, didn't actually pan out.

Underwood told BuzzFeed that Gur initially thought moving to mail service was a terrible idea, as did a lot of other investors. But Underwood said that once he committed to the idea of moving from to-do lists to mail, Gur "flipped the switch and got 100% behind and worked hard to help us make our new product as great as it could be."

Mailbox, a slick email application that Underwood built as a follow-up to Orchestra, went on to capture a lot of buzz and subsequently be acquired by Dropbox for $100 million.

The Allen & Co. of venture capital.

Perhaps because CRV lacks the name recognition — and press attention — of competitors like Andreessen-Horowitz, the firm has positioned itself more like an old-school investment bank: the trusted advisor whispering in the ear of the CEO, setting the strategic direction. It is the venture capital community's version of boutique media investment bank Allen & Co, whose annual Sun Valley conference attracts CEOs, billionaire portfolio managers, politicians, and celebrities to Idaho for a week of mostly press free schmoozing.

Similarly, CRV partners spend a lot of time "sourcing," or building relationships with potential entrepreneurs and other industry professionals, so that when a company with potential comes along the firm is in a position to act quickly and get in early on an investment, like with Pebble.

"I was pretty wary about VC investment for a long time. I had heard a lot of stories, plus I had been turned down dozens if not hundreds of times before we did Kickstarter and didn't have a lot of faith in them spotting smart people and companies," Pebble co-founder Eric Migicovsky told BuzzFeed. "I spoke with dozens of references — founders he had invested in, people he hadn't, friends, mentors, valley experts — and literally every single person had rave reviews. That sold me, and in March 2013 George [Zachary] invested $15 million in Pebble and joined our board alongside me."

Armony said CRV is content with being an "artisan" business, at least for the time being.

"In investment banking you have Goldman Sachs, the 900-pound gorilla that does everything, and Allen & Co., which is much more personal and finds the best entrepreneurs. You can be Toyota or you can be Porsche," Armony said. "You can build a big service organization, you can decide to go life cycle from seed to pre-IPO. I'm not too arrogant to say our way is the best, it's probably not the best, but it's a good fit for us."

Not coincidentally, its strategy is fitting well with investors and entrepreneurs, too.