The media business is gearing up for one of the biggest acquisitions of all time, as AT&T moves to buy Time Warner, the owner of CNN, HBO, and Warner Bros. But as the companies prepare to formally announce the deal, its likely opponents are already warning it should be rejected by Washington.

AT&T has agreed to pay $85 billion for Time Warner, the company said Saturday, in a deal valued at $109 billion once Time Warner's debt is included.

The deal, if approved by regulators, would be the most significant shift of media power since 2011, when another communications company, Comcast, took control of another giant news and entertainment conglomerate, NBC/Universal. AT&T said that the deal is expected to close before the end of next year.

“This is a perfect match of two companies with complementary strengths who can bring a fresh approach to how the media and communications industry works for customers, content creators, distributors and advertisers,” AT&T's chief executive officer Randall Stephenson said in a statement.

AT&T, which already has about $120 billion in long-term debt, said it will pay for the deal half in cash and half with stock. The company said the cash component will come in part from $40 billion in new loans.

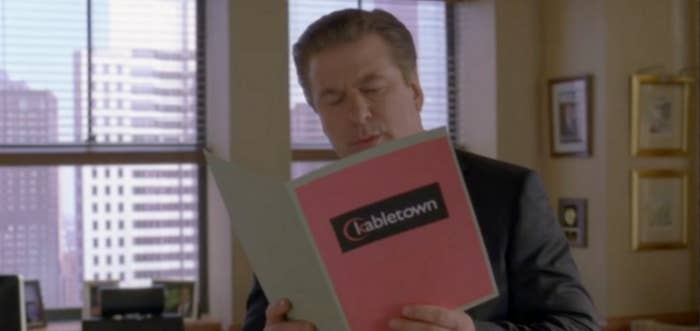

Having the cable company own the cable channels raises competition questions, and for those opposed to the consolidation of the media and communications industries, Washington's approval of that deal — immortalized by 30 Rock as the Kabletown merger — was a major failure of the Obama administration.

"Distribution companies and content companies should not be allowed to merge," Barry Lynn, a senior fellow at the progressive New America Foundation, told BuzzFeed News. "AT&T would never have dared propose this deal had the Obama Administration not erred fantastically in approving the Comcast takeover of NBC/Universal."

The Wall Street Journal reported the deal could kick off more consolidation of the media industry, as the owners of cable and mobile networks scramble to buy up the owners of TV channels and film studios. Some have speculated it could spur Comcast to make another purchase of its own — perhaps Discovery Communications, owner of the Discovery Channel, or Viacom, which owns Comedy Central, MTV and Paramount.

The merger of Comcast and NBC/Universal (which is an investor in BuzzFeed) was eventually approved in Washington after the cable giant agreed to a long list of "behavioral remedies" that would govern its conduct going forward. But the deal reportedly left a bad taste in the mouth of regulators, and the Wall Street Journal has reported the Justice Department investigated whether Comcast stuck by its side of the agreement.

"During the failed Comcast Time Warner Cable merger, there was a clear regulatory consensus that the behavioral remedies imposed on Comcast/NBC had failed, in part because the conditions were simply too hard to enforce/monitor," said Rich Greenfield, an analyst for BTIG, in a note Saturday.

Several major deals have run into trouble in Washington recently: In July, the Justice Department sued to block two giant mergers of health insurance companies, Aetna-Humana, and Cigna-Anthem. A deal to combine the oil services companies Halliburton and Baker Hughes fell apart thanks to regulatory opposition.

While the most obvious concerns about how mergers impact competition come when companies buy their direct competitors, deals like AT&T and Time Warner raise different questions. AT&T would own both content and the platforms that deliver it to customers — the DirecTV satellite television system, U-Verse cable network, and its own mobile network. In total, over 25 million subscribers get their TV from AT&T.

Comcast raised similar concerns when it bought a media business, but AT&T adds the America's second-largest mobile network, with 132 million subscribers, into the equation. So far, cellphone operators have made small moves into online and video content — Verizon bought AOL, and has agreed to buy Yahoo — but Time Warner would dwarf all that, and competitors could feel pressure to match it.

“What approving this deal would do is “cable-ize” the telecom industry. It would effectively require that a carrier own content. This would normalize a form of bundling that raises anti-competitive concerns," said Lina Khan, a fellow at New America.

"If competition authorities wanted to keep the market open to smaller phone companies and smaller content companies, they would find a way to block this deal."

Regulators could also worry that AT&T would use its own massive network for distributing video content — meanings its mobile network, DirecTV and U-Verse — to give a leg up to Time Warner's content over competitors that aren't married to a massive telecommunications company. "In our view, regulators will fear that AT&T will use its distribution footprint to favor Time Warner content vs. third-parties," Greenfield said.

AT&T said that the deal would make it easier to access "premium" content across devices: "A big customer pain point is paying for content once but not being able to access it on any device, anywhere. Our goal is to solve that. We intend to give customers unmatched choice, quality, value and experiences that will define the future of media and communications," Stephenson said.

The company also said that owning the content itself would help it sell advertising, bringing in another potential source of revenue besides the mostly-saturated mobile phone business and the declining cable business.

Approval for a deal would likely be decided by the next administration, Rachel Pierson, a managing director at Beacon Policy Advisors told BuzzFeed News. In October, the Clinton campaign rolled out an aggressive competition policy position, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren has already made a point of putting public pressure on her Democratic colleagues to support aggressive antitrust enforcement.

In July, Warren criticized the practice of the regulators allowing troubling mergers to go ahead if the companies agree to special terms and conditions, saying such conditions are rarely enforced.

"Regulators who didn’t have the political chops to block the deal in the first place are very unlikely to force the companies to break up after the fact," she said, "even if the companies blow off the conditions."