In accepting the biggest award of the night at the 2016 Grammy Awards, Taylor Swift spoke words of encouragement to other female artists as she highlighted her own milestone achievement. "As the first woman to win Album of the Year at the Grammys twice, I want to say to all the young women out there: There are going to be people along the way who will try to undercut your success or take credit for your accomplishments or your fame," she said. "But if you just focus on the work and you don’t let those people sidetrack you, someday when you get where you are going, you’ll look around and you will know that it was you and the people who love you who put you there, and that will be the greatest feeling in the world."

Her comment about “taking credit for your fame” may have made mild reference to a “misogynistic” verse from Kanye West’s album The Life of Pablo that name-checks the singer. But Swift’s sentiment about undercutting women in the wake of success was practically a prelude to reactions to come, to her taking home the Grammys’ most distinguished honor over Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd, Chris Stapleton, and Alabama Shakes. While some music fans simply favor Lamar's masterful rap set To Pimp a Butterfly over Swift’s 1989, others opted to use gendered, dismissive, value-driven, and derisive language toward the winner and the pop genre on social media.

Lamar versus Swift is yet another example in a long lineage of tough Grammy Awards competitions where issues of race, gender, and privilege intersect. Last year, Iggy Azalea earned four nominations amid accusations of cultural appropriation and protestations from hip-hop heads claiming her album The New Classic wasn't worthy of a Best Rap Album nod. In 2014, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis (who had already notably sparked further debate over "gay-friendliness" and hip-hop with their viral hit "Same Love") won three of the four awards in the Grammys’ rap categories, beating out critically favored artists like — you guessed it — Kendrick Lamar.

"Whenever we would hear from an individual who was complaining about Iggy Azalea, the first question we asked is 'Are you a member of the academy?' and, second, 'Did you vote?' If they answered no to either of those questions, they really didn't have a leg to stand on if they were eligible to do so," Bill Freimuth, the Recording Academy's vice president of awards, told BuzzFeed News in a phone interview in January. "The people who participate can change that process. We gained a lot of new members from the hip-hop community that are voting, and we're doing everything we can to encourage people to fill out those ballots."

And yet, it’d be no stretch to say unconscious biases — practiced even by newly vetted and hand-selected members of the Recording Academy — may still play a factor in Grammy nominations and wins. By definition, voters aren’t aware of such tendencies. The ire directed at Azalea may have taken on exceptional form because she was a female artist in those spaces. Swift, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, and Azalea enjoyed pop radio airplay and global recognition, but commercial success as white performers can also mirror the music industry’s unwitting partiality. If voters' tastes tend toward the most commercially viable and popular acts, the Grammys then become complicit in prejudice.

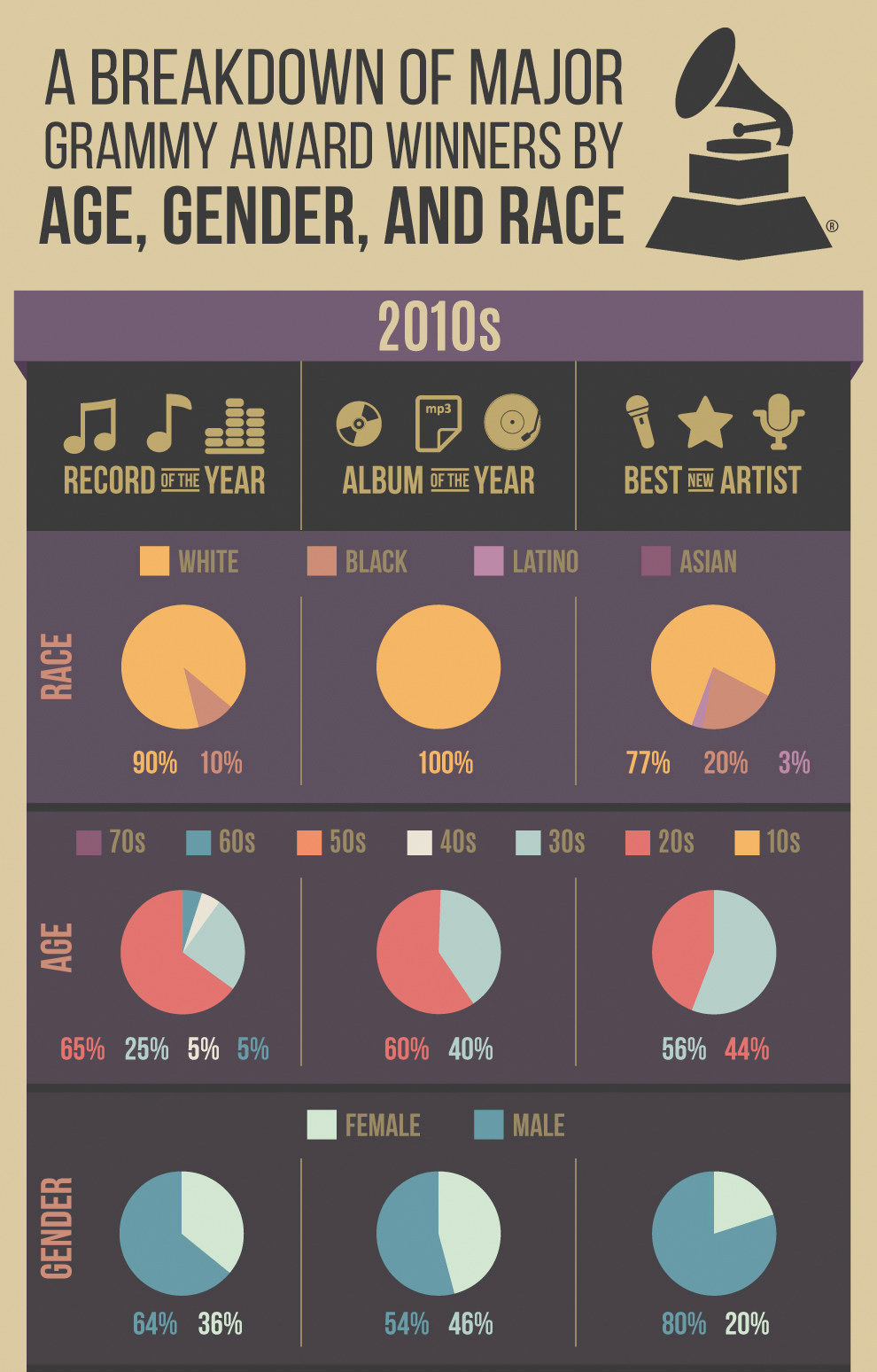

In February 2015, BuzzFeed News posted this breakdown of Album of the Year, Record of the Year, and Best New Artist winners by race, gender, and age, outlining the full extent to which white male dominance persists in every decade.

As is plain with that chart, which does not include 2016 nominations, the gender divide in entertainment doesn't exist on an island, but intersects with all manner of representation…and lack thereof. It’s futile at best and reductive at worst to qualitatively argue Lamar versus Swift as simply a matter of male versus female, black versus white, “urban” versus radio-friendly pop, or commercial versus critical.

It’s the latter that bothers the Recording Academy the most, year after year: They are still trying to shake the perception that awards correspond with an artist's popularity or sales. "The Grammy winners and nominees are not determined by money, not by label executives. They’re determined by the creative professionals working in the business who are listening to the music and choosing what they believe to be the best," Freimuth said. "Judging any artistic endeavor is highly subjective and nobody’s ever going to agree with all the winners, but I do believe that we have a process that — through its 50-some years of refinement — has gotten to a place where it does actually portray the consensus of the creative community in music as to what the best recordings are.”

The Recording Academy's rules for the Grammys underwent an unprecedented overhaul in 2011, and as a result, the Grammys got rid of its gender-based honors, for the first time in the awards' history. Eliminating male and female superlatives — for Pop, R&B and Country Solo Performance — helped the Grammys arrive on the other side with 28% fewer categories.

The gendered categories were established in the first place to combat sexism in the music industry. "In the early days of the awards, it was a very different time in the music business, a time in which women on the whole had a much more difficult time, not only as producers and engineers, but as artists, getting their recordings played on the radio, getting noticed," Freimuth said. But the Grammys didn't fold categories like Best Male Country Vocal Performance and Best Female Country Vocal Performance into a single, genderless category because sexism has been eradicated: They did so in order to give solo awards and nominations more weight, as part of a larger initiative to make the Grammys more competitive overall.

And five years on, Freimuth can recall only one person who threw any amount of stink about the de-gendering of categories. "To be perfectly honest, I was a little surprised of the minimal reaction to that part of our changes," he said.

The Recording Academy was worried at first about gender domination in those select awards, like women taking over the pop solo performance field, or male vocalists squeezing out female performers at country ("We weren't terribly concerned about R&B because that's been more even-handed along the way," Freimuth said). Since then, the fears over those categories have become a little less anchored in reality: 38% of the songs nominated for Best Country Solo Performance in the past five years were sung by women; and 60% of the nominations for R&B performance have gone to songs sung by a solo female (e.g., Tamar in 2016), a male/female duet (e.g., Robert Glasper Experiment & Ledisi in 2013), or by a female-fronted group (e.g., Hiatus Kaiyote in 2014 and 2016).

But, yes, 68% of nominations for Best Pop Solo Performance have gone to women, a clear majority. Personality powerhouses have helped to drive that wedge: Adele took the crown both of the times she was nominated. After moving from primarily country to all-pop, Swift added more estrogen to the latter field overall with seven nominations, and Katy Perry has kept the category consistently competitive with three nods after the 2011 rule change.

Of the three most recently gender-emancipated categories, women seem to have found or are finding decent footing in the competition. Those changes could have potentially affected the psyche of the Grammy voter for the good, with female and male artists like Carrie Underwood and Keith Urban going toe-to-toe in a category where they were previously separated. But this perception of equality for women hasn't always been the norm, and Grammy voters have a ways to go, in terms of gender parity overall.

For a comparison study on female performers at the Grammys, look to two other highly competitive popular music fields that flirted with gendered Grammy Awards: rap and rock.

Women and men competed together in Best Rap Solo Performance from 1991 to 2002 and from 2005 until 2011. Only 11% of the total nominees from those years were women (Missy Elliott and Queen Latifah claimed three a piece). Best Female Rap Solo Performance and its male counterpart lasted for only two years, 2003 and 2004 (Elliott won both years for the ladies), due to the low volume of entries.

"It's not to say artists like Missy Elliott and Nicki Minaj aren't really terrific at their craft; it's just that there weren't very many of them. Just by entering [Best Female Rap Solo Performance], one had a hugely improved chance of getting a Grammy nomination based on sheer numbers," Freimuth said. "Our trustees, in their wisdom, said, 'This is the highest award in music; we want to be very competitive in all of our categories.'"

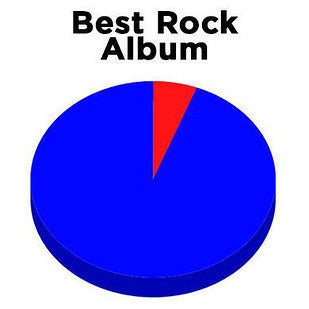

The category for Best Female Rock Performance ran from 1980 to 2004, and went on hiatus for three nonconsecutive years in between, also because of the small number of entries. From 2005 to 2011, only two (6%) of the total nominees were women — and neither won. Best Rock Song is batting about the same low average as Best Rap Song. There have been more metal/hard rock–nominated acts with female-inflected band names (Alice in Chains, Queens of the Stone Age, Jane's Addiction, Marilyn Manson, etc.) than there have been actual female-led nominees (Evanescence). In its five years of existence, 24% of the Best Rock Performance nominees have been women or female-fronted groups — six out of 25 total. Three of those six have been Alabama Shakes (who took home big Best Rock Performance and Best Rock Song wins on Monday), and four of those six were nominees from just the 2016 crop.

Freimuth said the academy is feeling positive about that last stat, however, considering Best Rock Performance was formed in 2012 by combining Best Solo Rock Performance, Best Rock Duo/Group, and Best Instrumental Rock Performances, making it "highly competitive." (In 2014, Hard Rock Performance also joined that fray.) "Certainly, it's not easy to get into," he said of the category. Women's nominations may be part of a trend, he surmised. "You can look at society on the whole and see that women are more empowered now than they were in, say, the '90s."

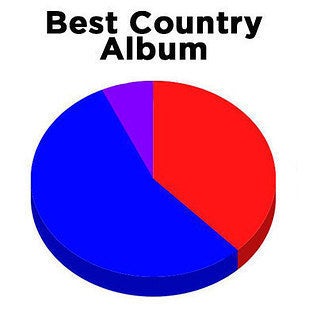

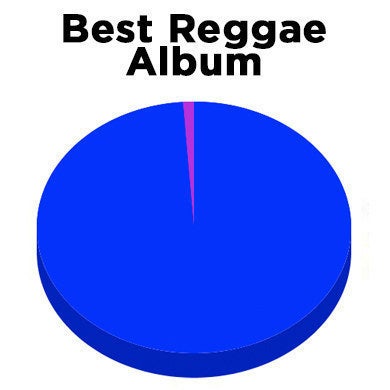

But the 1990s was also the last decade in which a woman won Best Rock Album, and the only era a woman has ever won Best Rap Album (which was Lauryn Hill, and only as part of the co-ed crew The Fugees). Granted, Best Rap Album was added to the awards only in 1995.

But whether an award has been around for five years or 55 years, men have much better odds of earning a nomination than women in almost all non-classical album categories.

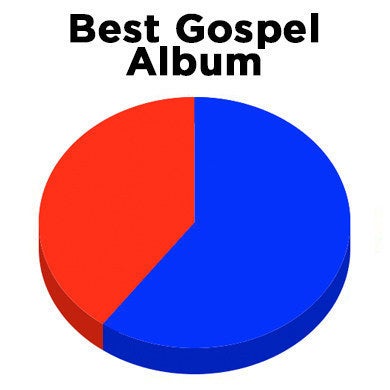

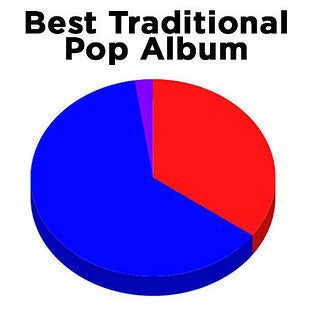

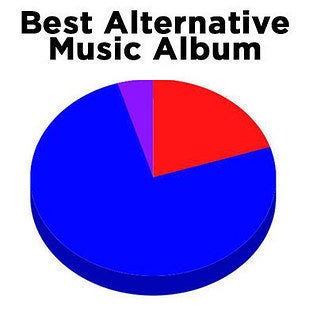

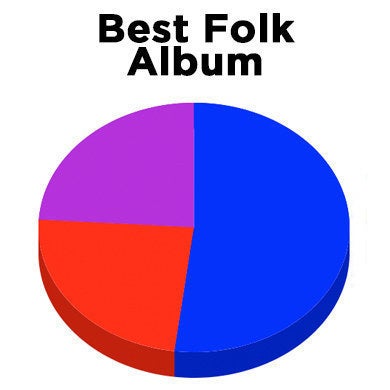

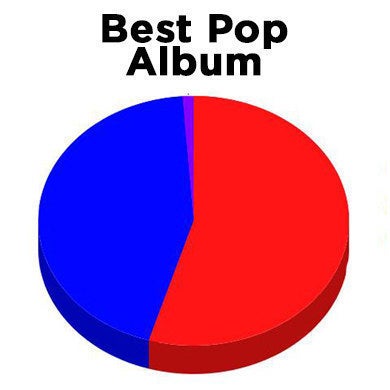

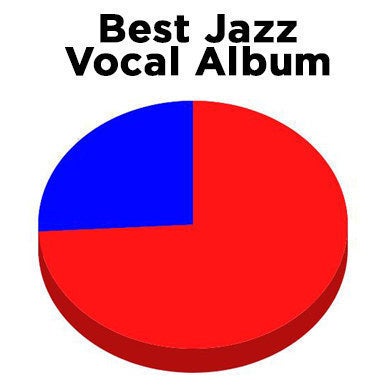

Here is a small sampling of vocal-led, non-classical best album awards broken down by gender from 2000 to present (some awards founded post-2000).

Best Jazz Vocal Album and Best Pop Album are the two non-classical

album categories with female solo artists and female-led groups as the majority of the nominees since 2000.

Album of the Year has been dished out 57 times in history: 13 of the awards have gone to a solo female artist, one has gone to an all-female group (Dixie Chicks), two have gone to a male-female duo (John Lennon & Yoko Ono, and Robert Plant & Alison Krauss), and two have gone to groups with women and men co-leading (Fleetwood Mac and Arcade Fire). One "various artists" album included many women-led songs (the soundtrack for ); and features-heavy winners like those from Quincy Jones, Santana, Herbie Hancock, Ray Charles, and the Bee Gees-helmed soundtrack also included some female guest vocalists. Even if you were inclined to circle all of the above, solo female, female-fronted, female co-led, and female-featuring albums still make up less than 40% of the Album of the Year winners tally. (If you think it'd be more even in the modern era, think again: Since 2000, only 35% the total are for solo female, female-led, or female co-led artists. The 1990s were particularly good for women.)

Nominations in non-classical instrumental music categories like regional roots, jazz ensemble, bluegrass, world, and new age are all male-dominated. And at this point, to say nonperforming Grammy-earning credits like producer, executive producer, engineer, and songwriter are lacking in female nominees would be a massive understatement. For example, only six women have ever been nominated for Producer of the Year (Non-Classical) — and none have won. Even though the vast majority of Song of the Year–winning tracks since 2000 were performed by female artists, fewer than a quarter of the credits for a Song of the Year win were given to women, because the award goes to songwriters, primarily men.

"There are very few engineers and producers who are working at a very high level that are female. Nobody's terribly happy about that," Freimuth conceded of the gender disparity in regard to technical awards. "Sadly, that just reflects the state of the business right now."

The state of the music business may mean that women are empirically making less rap or rock music, producing fewer albums, or writing fewer songs than men. Fewer women making art means fewer nominations, fewer nominations means less visibility, and less visibility means the perception that the music world is a "boys club" persists.

But a boys club may mean women feel dissuaded from participating, or don't see value in adding their perspectives to the artform. A boys club is also where sexism can more easily cultivate without challenge or correction: Dismissive attitudes toward women-dominated fields and honors persevere. Commercial or radio-friendly pop is frequently shrugged off as vapid, a less a legitimate art form, or framed as music for little girls. The Grammy for Best New Artist is heavily female-dominated (and Meghan Trainor picked up another win on Monday), and yet bears the reputation as a "kiss of death" and yielding one-hit wonders. While Swift encouraged female artists to "focus on the work," a woman's "work" in music can face additional scrutiny or tokenism.

So far, Freimuth said the Recording Academy hasn't given any new instruction on considering formerly gendered categories, or to sway voters to consider diversity during nominations for particular nominating blocs. “We do always encourage our voters to take the broad view and educate themselves with artists on the ballot with whom they're not familiar," he said.

As "Music's Biggest Night" marches forward in a supposedly gender-blind era, music's biggest stars may help tip the scales for nominations and wins. Swift has earned two Album of the Year honors, won two others for latest 1989, loaded up the cart with country wins at the start of her career, and shows no sign of slowing at the age of 26. International cross-generational and cross-genre headliner Adele has changed the name of the pop game in less than a decade, not just by rolling in the deep sales-wise: She's won 10 of the 13 Grammys she's been nominated for (and has gone eight for eight since 2012), and she's probably picking out a handful of dresses for the 2017 awards based on acclaim her latest album, 25, received. And, last year, Beyoncé became the new record holder as the most-nominated female artist in Grammy history (eclipsing multidecade phenom Dolly Parton). By dominating R&B categories over the years, on top of earning accolades in pop, A/V, and top categories, she's won 38% of her 53 nominations, besting her husband Jay Z's winning average, 33% (21 for 64).

Along with big wins for Swift and Alabama Shakes, there were even more crowning moments for female artists and songwriters on Monday, including multi-Grammy Award winner Angélique Kidjo for Best World Music Album; Natalia Lafourcade in a tie with Pitbull for Best Latin Rock, Urban or Alternative Album; Lori McKenna, Liz Rose and Hillary Lindsey, the trio of ladies behind Best Country Song "Girl Crush"; Lalah Hathaway for Best Traditional R&B Performance; and Judith Sherman for another Producer of the Year (Classical) win.

Still, five ceremonies since gendered categories were nixed, 16 years into the new millennium, and decades since sexual revolution in America, there’s so much male/female divide at the Grammys, it's hard to say that it's a fair contest — or at its most healthfully competitive — yet. But there is increasing consciousness of the disparity, and a number of female-led groups and female solo artists still trying to earn their place at the table.

Just as the Grammys reflect and award an unbalanced music industry, the Oscars reflect the “state of the business” in Hollywood. The Academy Awards have been raked over similarly hot coals and made their own internal adjustments in order to grapple with matters of voting and diversity. On the heels of #OscarsSoWhite year two, the awards' leadership recently vowed to be the change we want to see, revamping policies around its voting body and membership recruitment, changes designed to add the perspectives of more people of color, more women, and other underrepresented communities over the long-term.

And just like the Grammys, the Academy Awards aren't just a mirror of an industry struggling with diversity: They have their own power to influence how people think about film, pop culture, and their world. On the flip side, the Oscars can't be held responsible for all blights of discrimination in Hollywood — like jaw-dropping wage gaps, and the prevailing white-maleness of filmmakers behind best-funded films. After all, a number of other creative institutions have foundered the same (and sometimes more extreme) ails.

The Oscars would have a much harder time throwing out gendered categories than the Grammys did, since among 24 awards, only four Academy Awards are based on performance (Best Actor/Actress, Best Supporting Actor/Actress). And even those four have proven problematic, like rewarding actors for playing transgender characters in a modern society where gender/sexual non-binaries and fluid identity is increasingly recognized. While the Grammys tend to honor an artist's authenticity (rather than, say, their concepts or alter egos), an Oscar-nominated actor's authentic "self" is expressly taken into consideration of the way they play their role, thus, there is an overt emphasis on "male" and "female" performances.

What would happen if the gender divide — if just on the performance level — were to disappear? What changes if Cate Blanchett's closeted Carol was suddenly in competition against Eddie Redmayne's transgender character in The Danish Girl? Or if Kate Winslet as a marketing executive in Steve Jobs had a face-off with Tom Hardy's unsavory fur trapper in The Revenant? Conceivably, it could inspire rethinking what defines a "best" effort by an actor, or further reveal how voters think about how male and female protagonists' stories are told differently. As it has at the Grammys, perhaps it would more expediently expose tokenism or voters' overt or unconscious biases about gender and gender roles (or race, age, economic status, societal norms, commercial viability...) on top of making artistic spaces truly more "competitive."

Recognizing imbalances — the many different kinds, and the many reasons for them — anywhere in the awards world can influence change to rules and regulations, further examination of categorical shortfalls, better voter recruitment, more complete ballots, and less indifference for "the state of the business." The road to parity is long, its victories perhaps only on a slow and psychic level, but such changes at least step toward resolution, rather than perpetuate the industry's ills.