Clicking on an icon selects it, double-clicking opens the file. That relationship has always been dependable; something I've always been able to count on whether I'm using a Mac, a PC or a Linux machine. Select, open. Preview, execute. Highlight, do. But the double-click gesture, which you can still probably hear in your office if you listen closely enough, is on its way out.

Double-clicking is dying.

Do something with your phone. Now watch your thumb. You'll never see a double-tap outside of a game, maybe. Pick up your tablet. Watch your finger. Lots of tapping, none of it grouped. Now, even worse, get your hands on a new MacBook and and look at what's really different about the software. You'll find lots of new gestures, and an iPhone-style app launcher. There's a screen called Mission Control for managing desktops and apps. You can still double-click on the old stuff — the lists of icons in Finder, the app title bars — but there's no double-clicking to be done with the new. Ditto for Windows 8 — Metro is a touch-based mono-tap utopia. Apple and Microsoft, the companies that invented and standardized double-clicking, respectively, are the same ones who are putting it to sleep.

The Apple Lisa was the first computer regular people (well, regular people with 10,000 spare dollars in 1983) could buy that had a graphical user interface. The interface, though, wasn't fully Apple's. It wasn't until Steve Jobs visited Xerox's campus in 1979 that he was fully sold on the GUI concept; so sold that he and his team borrowed liberally from the Xerox Alto, a personal computer that never quite made it to market, in designing their first GUI.

One feature they could definitely take credit for, though, was the double-click. Xerox didn't come up with that; Apple designer Bill Atkinson did.

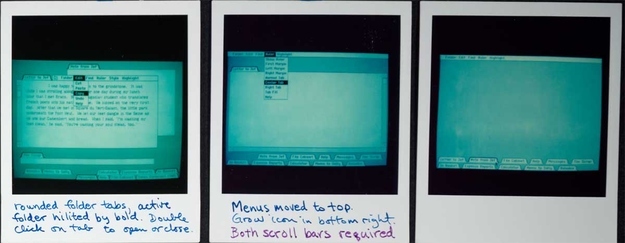

Atkinson took Polaroid photos to document milestones in the Lisa development process, many of which have been collected by his cohort, Andy Hertzfeld. One bears a note about "double clicking" on a tab to close it; this may be the first known documentation of the behavior.

(The next photo records the moment when they decided to move the app menu from individual windows to the top of the screen, where it's stayed ever since. History!)

Double-clicking quickly became standard across the software industry. It stuck around in Mac OS. It was in Windows 1.0 and every edition thereafter, though there was an awkward period of experimentation with single-click, link-style behaviors in Windows 95 (with the Internet Explorer 4 update) then in Windows 98 and, most prominently, in Windows ME.

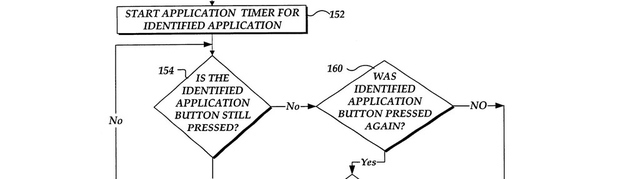

In 2002 Microsoft filed for a double-click patent, which was granted to the company in 2004 — I can only assume it was seen as so unenforceable and the "technology" as so old that nobody, not even Apple, decided to make much of a stink about it. In any case, opening a file in Windows 7 is just like opening a file in Windows 1.0, and running an app from OS X finder is just like it was in the original Mac OS: clickclick, then wait.

The first big blow to the double-click's dominance was the web browser. In Tim Berners-Lee's first preliminary specification for HTML, published in 1992, here's how he explains the most important new aspect of Hypertext — links:

If the reader selects this text, he should be presented with another document whose network address is defined by the value of the HREF attribute

In an HTML page, unlike in a desktop file system, there's no need to drag and drop, or to select a file then choose an action for it. There was only one type of interactivity in HTML: following a link. Double-clicking links would be pointless extra work, so web browsing programs don't require it. This created a small disconnect — I still occasionally catch older family members double-clicking on links — but we all got used to it.

The second blow, a much larger one, came with the finger-sensitive touchscreen. Early touchscreen smartphones, which relied on stylus input, kept double tapping. Palm OS and Windows Mobile were basically scaled-down desktop operating systems, and they maintained their larger brothers' interaction chains. Every action was a deliberate selection, then an activation. Even scrolling was a secondary action that you could only do after selecting the scroll cursor.

The iPhone changed the order. Its software understands touches thusly: if a finger contacts the screen and moves, the software scrolls. If it contacts the screen and is quickly removed — a tap — the software effectively clicks. In most iPhone apps, and now Android and Windows Phone apps, there is no need to select something before activating it. You just tap. (Double-tapping has its place in all three mobile OSes, mostly for zooming, but it rarely does anything another gesture can't do better.)

If the future is mobile interfaces, the future has no place for double-click, not least because the future has no place for a mice. Even in the meantime, on laptops and desktops, the double-click is being pushed aside in favor of touch gestures. In Mac OS Lion (and the next version, Mountain Lion), double-clicking will stick around in the older, desktop-derived areas of the operating system: the file system, iTunes, Mail. Same for Windows 8. But it wouldn't be surprising in the slightest to see its ancient spirit exorcised from Mac OS 11, or Windows 9. Double clicking is already vestigial.

So goodbye, double-click. My children may never know you, but my finger muscles will never forget.