The government can read your email. They can read your search history, your chat logs and your file transfers. "They quite literally can watch your ideas form as you type," according to the whistleblower who leaked documents describing the NSA's digital surveillance program to the Washington Post.

The oft-imagined, never confirmed program under which the NSA claims to have "direct access" to the servers of the largest internet companies became real today. And we learned its name: PRISM.

PRISM is a tremendous revelation on its own. But it's also a the finest data point yet in the tech world's most subtle, and significant, convergence of trends. It's confirmation that the government is as eager to access user information, and that companies are as willing to give it to them, as we are to give it away in the first place. It's proof that the companies we trust with our identities are, in a very real way, private data aggregators for intelligence agencies.

Every year Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and a host of other companies, large and small, new and old, demand more and more data from us. Whether it's Google aggressively lobbying to pad our already horrifying Search dossiers with social networking data and literally wearable computers, or Facebook transitioning from a service that doesn't just host the information we consciously give it but rebroadcasts our actions for the world to see, the pattern is obvious to anyone who lives online: internet companies want to know everything, and often all they have to do is ask.

What was less obvious to the average customer was that the government's appetite for our data is at least as voracious Google's and Facebook's, and its goals, while different, are just as specific.

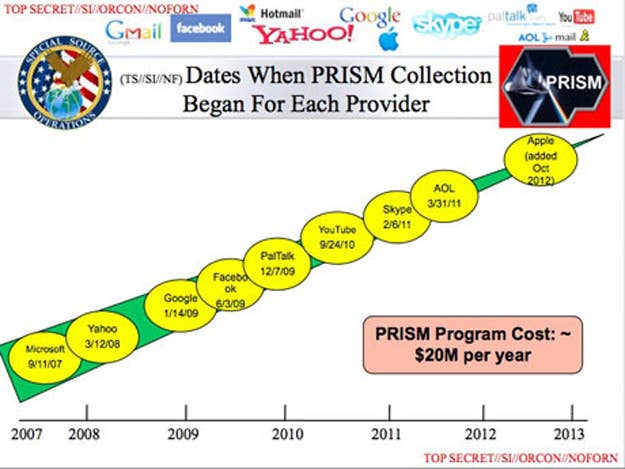

The tiny $20 million program budget listed in the leaked documents speaks to just how unstoppable PRISM-like programs are; judging from the limited evidence we have, this was neither a major technological undertaking for the government ($20 million would get the NSA nowhere on a true mass-monitoring project unless it had help from the companies it's monitoring) nor a public fight. Google has raised a vague stink; Twitter, which was not listed but hasn't responded to the reports yet, has made a point of fighting the government in a few high profile cases. But if the tech giants wanted to put up an all-or-nothing fight, it would be in their interest to make it a public one. In other words, we would know.

The companies that have responded to requests for comment have so far offered varied, incomplete and very carefully worded denials, denying specific details about PRISM rather than offering full-throated denunciations of secret government cooperation. Even the most adamant denials suggest greater cooperation with the government than most people are aware of.

But what other strategy do they have? This program, despite the leak, is still "secret," and unless more information about it comes to light — and keeps coming to light, until the program is fully illuminated — they can depend on the public to do what it's almost always done when faced with evidence of large-scale government surveillance: to forget about it.