Default settings matter.

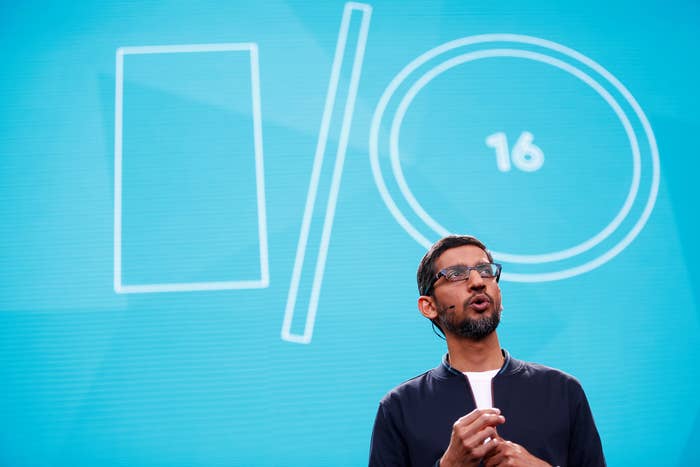

This truth of consumer technology brings significance to Google’s decision, announced Wednesday during its annual I/O developer conference, to offer end-to-end encryption through its new messaging app, Allo. But unlike WhatsApp or Apple’s iMessage, if you want the protection it offers you’ll have to turn it on.

Through an optional “incognito” mode, Allo encrypts communications in such a way that not even Google can access the contents of the messages you send. Only intended recipients can read correspondence when its end-to-end encrypted. For the majority of people, built-in settings are the ones most often used. That's why Google's decision to add end-to-end encryption as an option in Allo — but not enable it by default — is disconcerting to some technologists.

“Defaults are what everyone but the most technically savvy people end up using,” Jeremy Gillula, a staff technologist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told BuzzFeed News. From the perspective of consumer security, opt-in models tend to fail for the simple fact that most people don’t use them, he said. “We would certainly encourage Google to do the right thing and just make everything end-to-end encrypted.”

Google told BuzzFeed News that consumer choice and control were central to building security and privacy into Allo. The incognito mode in which end-to-end encryption is featured does not offer the most responsive and tailored services that would otherwise be available to customers who are chatting through Allo’s regular settings.

“Google has given the FBI exactly what the agency has been calling for,” Christopher Soghoian, the ACLU’s principal technologist, told BuzzFeed News.

Google’s “smart” replies and virtual assistant improve with use, “learning” by analyzing conversations and context. But this kind of fine-tuned processing requires a record or “memory” of chats that take place in the normal settings. Similar to Google’s web browser, Chrome, which includes its own incognito mode, the normal settings offer a more intuitive experience to consumers, Google said. The option to turn on incognito mode in Allo and enable end-to-end encryption offers additional security, but with the choice to revert back to the fuller version, Google added.

But others are concerned with the broader ramifications of Allo’s design. “Google has given the FBI exactly what the agency has been calling for,” Christopher Soghoian, the ACLU’s principal technologist, told BuzzFeed News.

Last month, WhatsApp rolled out end to end encryption — by default — for all its customers, a decision that continues to draw intense criticism from FBI officials. FBI Director James Comey has argued in recent years that robust consumer encryption has led to a crisis in law enforcement. As secure communication tools become widely available and easy to use, more and more electronic evidence remains out of reach for law enforcement. For Comey, end-to-end encryption provides a sheltered space for criminals and terrorists to conspire and conceal wrongdoing.

Since last year, Comey has suggested that technology companies consider tweaking the security products they offer. By providing encryption tools that also enable law enforcement to access the secure data, Comey has argued that the crisis of encryption can be partially resolved. In December, in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Comey told lawmakers that while encryption will always be available to savvy criminals in some form, one major dilemma for law enforcement is its widespread availability.

"Encryption is always going to be available to the sophisticated user,” Comey said. "The problem we face post-Snowden is: it's moved from being available to the sophisticated bad guy to being the default."

But even as law enforcement officials make their case against robust encryption, not even the most sophisticated security tools are foolproof. With end-to-end encryption enabled, the metadata surrounding the contents of a message — when it took place, and who was communicating — can still be pieced together, forming a kind of silhouette of crucial information. And malware installed on a computer or phone can capture what’s being typed even before it’s encrypted.

Google expects consumers to spend most of their time in Allo’s normal chat mode. The company said also that the benefits of smart features, added privacy settings, and being mindful of larger discussions within the tech industry were all factors in how Allo was designed.

Allo will launch this summer on both Android and iOS, with Google bringing its latest messaging product to the two largest smartphone platforms around: According to Gartner, the two platforms combined represent more than 98 percent of the world's smartphone market. (Caveat: Google currently has multiple messaging products, not all of them widely used.)

The ACLU’s Soghoian said that while it’s unclear what role political decisions played in influencing Google’s product design, “It isn't really possible to offer an AI chatbot while still having end-to-end encryption.”

“Google might just be betting that AI chatbots are going to win them more users than default security,” he said.