After his 17-mile hike along the Appalachian Trail, Bradley Veeder thought the flat mountaintop meadow was the perfect place to pitch a tent for the night and go to sleep. Then he was bit by the bear.

“I felt a sharp pain in my right calf and an agonizing sensation like my calf was being squeezed in a vise,” wrote Veeder, 49, about the May 10, 2016, bear attack in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina. A black bear had bit him through the tent, leaving one-and-a-half inch deep holes in his right calf, and then tried to come in through the tent’s opening.

Yelling and punching at the animal, Veeder dissuaded it long enough to limp through the dark woods to a cabin shelter. Hikers who returned to the campsite the next day found his tent shredded and his gear gnawed.

Black bears don’t routinely attack people. But this one was dangerous, and now loose in a national park that sees 10.7 million visitors a year and has 850 miles of trails.

“People don’t like it, our biologists don’t like it, when we have to put an animal down,” park management assistant Dana Soehn told BuzzFeed News. But more than 1,500 black bears live in the national park, and about once a year, a hiker is attacked.

As recently as a few years ago, these attacks would lead rangers to killing any suspect bears. But now, Soehn said, “DNA tests can now exonerate bears who might have been euthanized before.”

At a big DNA conference this past week, a scientist reported how to quickly test the bear slobber left after the May 10 attack.

“We’re taking DNA techniques from human criminal investigations and using them on black bears,” Maureen Hickman, a wildlife geneticist at Western Carolina University, told BuzzFeed News. She presented her work at the International Symposium on Human Identification in Minneapolis. “It worked beautifully, there was a lot of saliva on the tent shreds, and there were bite marks on a phone and a book.”

Three days after the attack, park rangers caught a large, 400-pound male bear nosing around the trashed campsite. Despite folklore about mother bears with cubs posing the most danger, male black bears were responsible for 92% of the recorded fatal maulings over the last century. And this particular 400-pound bear had a chipped tooth that matched the bite marks on the book and other items.

“Our biologists have found that most of the time, the bear responsible for an attack returns,” Soehn said. Two more male bears, both smaller, were also captured at the attack site within a few weeks. Hickman tested DNA from all three bears against the sample from the ravaged gear at the campsite.

The DNA test, first created by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife forensic lab, relies on eight genetic markers that are unique to black bears but vary wildly from one bear to the next.

“The statistics work just like human forensics,” senior wildlife forensic specialist Erin Meredith of the California lab told BuzzFeed News. Only twin bears, which she has never seen, could fool the markers. “In case where there has been an attack, we want to know right away, and we want to find the right bear,” she said.

The approach is a reasonable one for finding rogue bears, University of Calgary black bear exper Scott Herrero, who wasn’t part of Hickman’s team, told BuzzFeed News. And it is becoming increasingly common.

Unlike older DNA tests that took weeks, the new markers let Hickman check a suspect bear’s DNA in less than seven hours. For the May 10 attack, it turned out that none of the three suspected bears were the real culprit.

That wasn’t soon enough to save the 400-pound guy. Biologists tried to fit a tracking collar on the bear, but he was too big for any collar, Soehn said. The rangers couldn’t free a bear they thought had attacked a hiker. If the bear had weighed 300 pounds or less, or was closer to a road instead of six miles away, they could have carted it to the Knoxville Zoo. But faced with a bad choice, park biologists had to shoot the bear, a decision that generated embarrassing headlines after the park learned the DNA results.

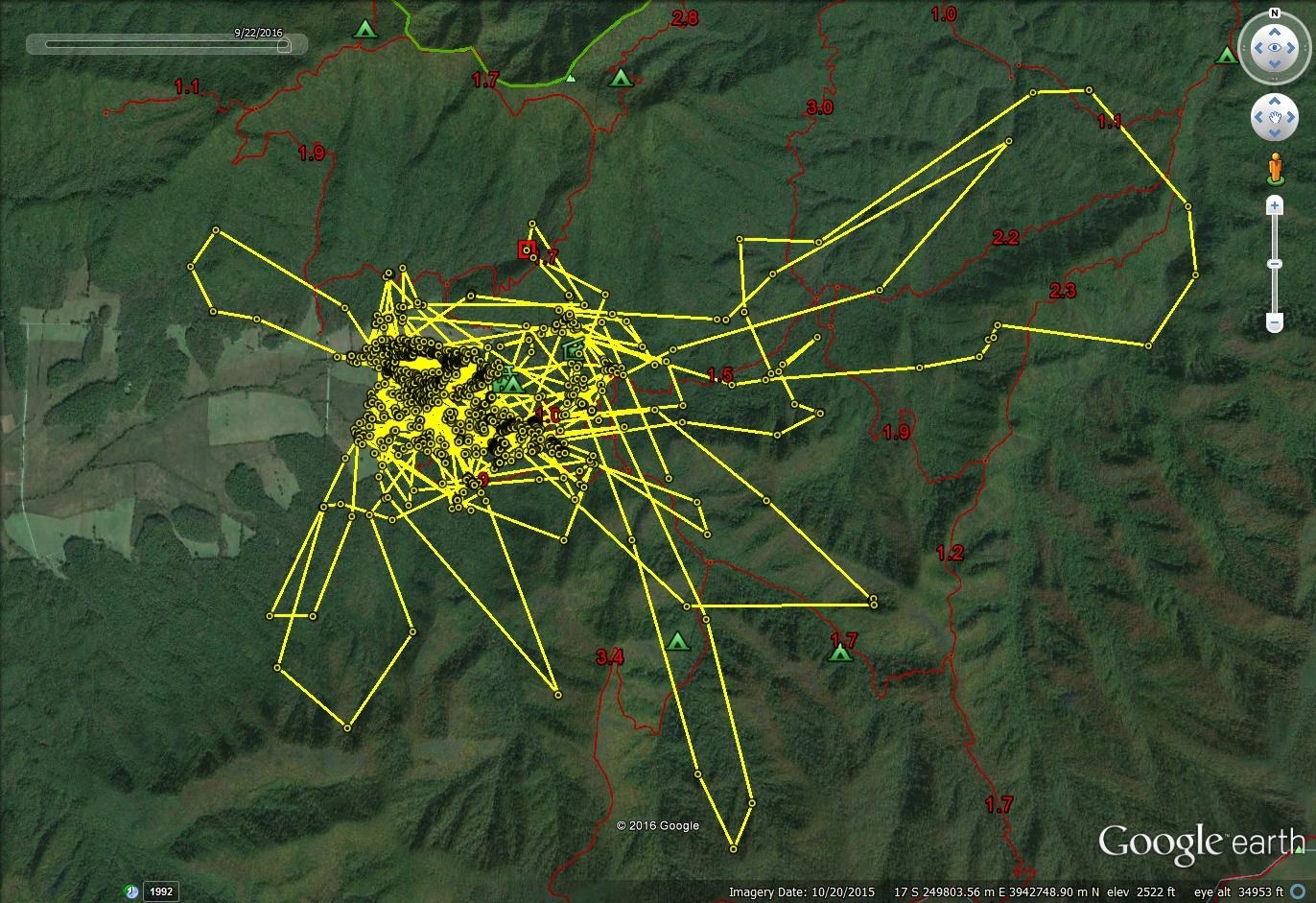

“At that point, we really thought we had the right bear,” Soehn said. With the other two suspected bears, the park had worked out how to get DNA samples quickly to Hickman’s lab, and they were freed, with tracking collars. (The park tracks the movements of about 30 bears with collars to find problematic trash or picnic areas.)

Nobody wants to kill the wrong bear again, Soehn said, “and we now have the opportunity to really quickly get DNA results back from the field.”

Male black bears are especially hungry in early summer, before berries ripen, so that’s when they’re most dangerous. Even an experienced hiker like Veeder, who had done all the right things, such as hanging his food from a bag at the shelter far from his tent, needs to watch out. Veeder said on his blog that from now on he will carry bear spray and camp with a large group.

Future DNA tests for rogue bears will hopefully include a sex marker, Meredith said, which is missing now (the catch is that human X or Y chromosomes from blood left after a mauling could confuse gender results from the bear’s DNA.) “Bears are easier in some ways than human criminals, who know they shouldn’t leave DNA behind,” she said. “Bears are pretty sloppy.”

And yet, the bear that attacked Veeder is still at large, Hickman said. “But at least we have his DNA now.”