On April 26, 2005, someone murdered 26-year-old Janet Abaroa, stabbing the young mother to death in her own home while her 6-month-old child slept nearby.

Her husband, Raven Abaroa, who had called 911, distraught, to report her death late that evening, quickly emerged as a suspect. His knife collection was suspiciously missing from the house, for one thing. A few months earlier, he had been caught embezzling from his employer. And he stood to benefit from his wife’s $500,000 life insurance policy.

Abaroa had an alibi, however, and maintained his innocence. He was playing at an evening soccer game around the time of the murder, not long after his wife had been seen alive. And so the Durham, North Carolina, case went cold until five years later, when a Durham detective named Charles Sole went over the evidence one more time.

Sole couldn’t get over one detail: When combing through the Abaroa house, investigators had never found Janet’s contact lenses. That was odd, because Raven Abaroa had claimed his wife was in bed watching TV when he left for the soccer game. And, as Janet’s friends and family told Sole and other investigators, taking out her contact lenses before watching TV was part of her nightly routine.

“So what happened was, a detective called me and asked: Would it be possible to identify contact lenses from a body that had been exhumed after five years?” ophthalmologist Charles Zwerling of Goldsboro, North Carolina, told BuzzFeed News. “I told him contact lenses disintegrate, but never say never, I would be willing to try.”

Nine months later, Zwerling heard that Janet Abaroa’s body was being exhumed to see if the contact lenses were still on her eyes. One of her husband’s defense attorneys objected to the exhumation, arguing that the contact lens experiments “have no scientific validity, will be performed without a specific or established protocol, and are designed to support conclusions the analysts have already reached.”

The complaint caught Zwerling’s attention as the legal fight over the exhumation played out, and he began to research the forensic science of contact lenses. It turned out, as he described in a study published this week, there was hardly any.

Courtroom science has come in for some harsh criticism in the last decade for being unscientific. A 2009 report the National Research Council concluded that, aside from DNA testing, “no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual.” More recently, the FBI Laboratory has acknowledged botched hair “matches” and bite-mark analyses in criminal cases going back decades.

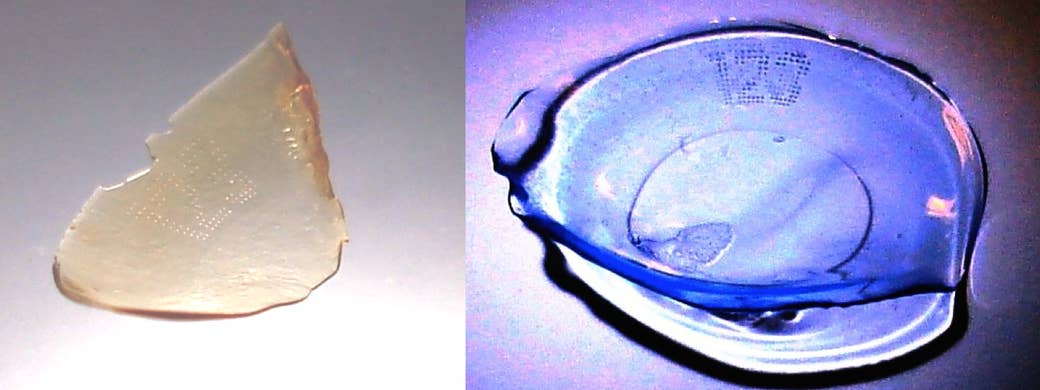

In 2013, Zwerling received an evidence package from investigators. Inside was a plastic bottle holding crumpled shreds of plastic, yellowed, shriveled fragments of contact lenses, removed from Janet Abaroa’s eyes. Zwerling washed the plastic with a saline solution and placed them under a microscope.

“The closest thing to a Eureka moment in all of this was when I added saline solution and watched a fragment just bloom under a microscope, unfolding and revealing an identification number,” Zwerling said. The number — “123” — was printed on every pair of those particular soft lenses, sold under the name Acuvue 2, which had been Janet Abaroa’s brand. So, counter to her husband’s story, she hadn’t taken them out before being murdered.

“The district attorney called and asked if I had anything, and I said, we sure did,” Zwerling said. “They had caught him out in a lie.”

But that wasn’t enough to make the contact evidence fit for the courtroom. Zwerling had to demonstrate that lenses dehydrate after burial, and then rehydrate, in exactly the same way as the ones from the exhumation had.

He found a proposal, published in 2000 by a forensic archaeologist in the U.K., which suggested burying contact lenses on pig eyes to see how they degrade over time. “Pig eyes are the closest ones to human eyes,” Zwerling said. “Only larger.”

Intrigued, Zwerling learned how to embalm bodies from a North Carolina funeral home team, and then carried out the technique on two sets of pig eyes with contact lenses on them. He wrapped them in typical funeral linens, placed them in small wooden caskets, and buried them six feet underground. He retrieved the first casket after six months and the second one after a year. The lenses inside had shriveled and discolored exactly like the ones from Abaroa’s exhumation.

“In forensic science sometimes you have to demonstrate things that happen in a murder case and you can’t exactly experiment on people,” forensic scientist Lawrence Kobilinsky of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, who was not part of the study, told BuzzFeed News. “A pig is the closest thing we have to a human, and in a murder case, you need a very solid simulation to what happened, of course.”

In March 2013, Abaroa was tried for the murder of his wife. Zwerling presented his contact lens evidence to a jury, without questions from the defense team. The murder case hung largely on discrepancies in Abaroa’s testimony to the police about the night of the murder, including the contacts. Durham district attorney Charlene Franks acknowledged to Dateline NBC in 2014 that she had no witnesses, no weapon, and no blood in Raven Abaroa’s car from the night of the murder.

The trial ended in a hung jury, 11-1, with one juror holding out for a not guilty verdict. Before a new trial could begin the next year, the district attorney accepted a so-called Alford plea from Abaroa, which meant that he didn't admit guilt but agreed that prosecutors likely had enough evidence to convict him.

“With this plea agreement today, Raven has finally admitted, after almost nine years, that he did in fact kill our beloved Janet,” her family said in a statement, expressing disappointment but acceptance of the plea.

Abaroa maintained his innocence, meanwhile, and said he took the plea because it meant he was eligible for release from prison, perhaps in as soon as four years.

“This was one of those needle-in-a-haystack cases,” Zwerling said. The biggest surprise, he learned while working at the funeral home, is that morticians are supposed to remove contact lenses before they bury people in North Carolina.

“If she had been wearing colored lenses, they would have removed them, but they were clear lenses,” he said. “That’s why we caught him.”