There was really no reason to think that the “Ace of Spades HQ Decision Desk” would be a hopeful sign for American democracy in 2014.

The Decision Desk swings into action on primary election nights, with Brandon Finnigan, a burly 29-year-old, nailed to a busted black leather armchair at one of those cheap beige aluminum desks, halfhearted fake wood top, toward the back of a low-slung house at a truck stop crossroads deep in California's monotonous Inland Empire. Dripping sweat every day since the air conditioner broke, Finnigan is the sole employee of a small truck dispatching company where he pulls the noon-to-midnight shift. He manages the dispatching job on one computer monitor. Finnigan's second monitor, however, is for election results.

Between calls from drivers broken down in San Diego, and between visits from men there to drop off paperwork, he tracks election results for Ace of Spades HQ, a conservative blog run by an anonymous, combative figure known only as Ace. Ace and his site’s mission has not, historically, been the sort of thing David Brooks gets excited about. The blog's motto is, “Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.” Its founder’s scabrous style of parody has at times given offense: “Please don’t call Sandra Fluke a slut,” he tweeted (and later deleted) of the abortion rights advocate and liberal icon . “Respect her for what she is, a shiftless rent-a-cooch from East Whoreville.”

And yet, politics is always surprising, and the eternal Washington consensus — that anything that’s good for democracy must come from the center — has not been borne out here.

Finnigan — along with his dozens of volunteer Google spreadsheet jockeys — is the most ambitious face of a major and democratizing shift in the way Americans learn about the results of the most important elections in the country.

“I want to fundamentally change how results are reported,” Finnigan told BuzzFeed News. His goal is both to modernize the local election boards and to deflate what he sees as false drama imposed by slow Associated Press calls and desperate television commentators. “I understand you need an element of suspense and you need something to jibber-jabber about on election night. But you got to jibber-jabber all year. I just want the results.”

Until about 2011, the way Americans received their information — who won, who lost — was dominated by the television networks. Their theatrical presentation and deliberate mystification turned their "analysts" — smart, numerate political hands with years of election experience — into a kind of political priesthood whose calls, particularly in the disputed 2000 election, were alleged to have shaped the outcome of a close race. Virtually all other contests were "called" by only one entity: the AP. The news wire neither rushes nor explains its decisions, which have been turned into a different kind of mysterious black box in part because it is bound contractually to share its results first with the news organizations who pay for those decisions. The AP essentially controlled when Americans learned who won an election.

But something significant has changed in the last few years: The geeky new obsession with political data. It really started with liberal bloggers who took polling seriously, and with the nerd king Nate Silver, who made his name reassuring Democrats that Barack Obama was, still, winning.

The conversation has moved from polling to the polls. The people counting the actual votes — county officials across the United States — have started putting precinct-by-precinct tallies online. Now that same data that only the AP could access, anyone can access. And so a group of a couple dozen devoted journalists and partisans assemble on Twitter on Tuesday nights through the summer and fall to watch election returns, county by county, pop up on the websites of registrars and clerks. They parse the results as they come in, they argue over what they mean, and sometimes they catch the sort of substantial errors — transposed digits, or uncounted ballots — that happen occasionally in preliminary election counts. They typically reach a consensus about who will win long before the AP has made its once-definitive call, based on the same factors the AP looks at — the likelihood that the candidate who trails in the vote can close the gap with the outstanding votes, given both statistics and the voting history of the precincts waiting to be counted.

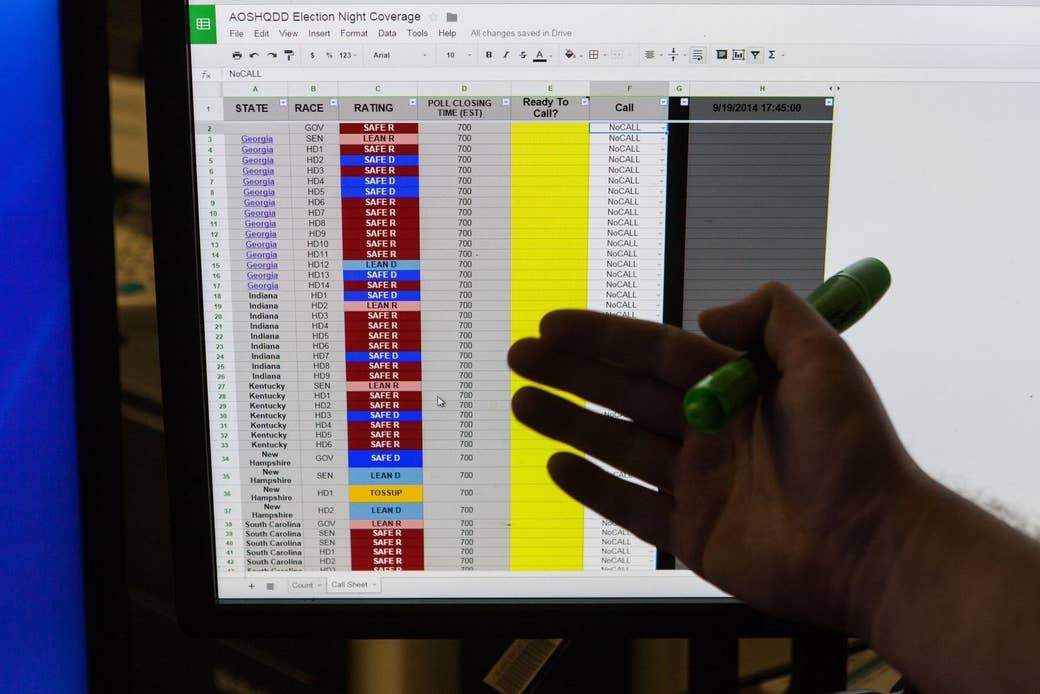

Now Finnigan and his ragtag Decision Desk have taken that transformation a step further. His volunteers, unlike the rest of amateur and professional media alike, don't just rely on published figures and AP tallies. They've also begun to replicate the AP's vast information-gathering network at the clerks' offices that don't report data swiftly online, organizing a cadre of what's now 130 volunteers to collect results directly from local officials. It's the next logical step for the small fraternity of election-night analysts, doing in public what the large media institutions have typically done in the dark. And while they have a tiny fraction of the AP's roughly 5,000 local reporters gathering results, they naturally focus on the relative handful of races of national interest, and have become central to a political conversation that has been for years now shaped on Twitter. Their slick website, built by a volunteer developer and blogger named John Ekdahl to aggregate both polling and election results, relaunched this week.

The volunteer election callers have caught major errors, including thousands of uncounted votes in Virginia’s Fairfax County last year. They've also hashed out bitterly partisan controversies in remarkably objective terms. And perhaps most importantly, they've punctured the mystery around the mechanics of democracy and produced flashes of consensus in a country whose partisans often seem to occupy different realities, and whose media have never been less trusted.

"Those of us in the amateur election projection world on election night are using our familiarity with the nooks and crannies of geography to beat the AP to the punch. The AP's job is to be cautious, but most of the time these elections can be called well before the AP does," said Dave Wasserman, an editor at the Cook Political Report who tweets from @redistrict (and caught the Fairfax County error), but laments that he has to be absent from Twitter for big election nights — because he's under contract to NBC.

AP's Washington bureau chief, Sally Buzbee, said she welcomes the Twitter conversation.

"Anything that helps people understand how elections happen and the process and of democracy is terrific. Transparency is wonderful," she said, adding that participating in the Twitter conversation would distract analysts from their jobs and undermine the organization's core mission. "Everybody in AP is comfortable that we don't break news on Twitter — we break news by giving our stuff to news organizations."

But the participants in the new, live results conversation see the AP as a stodgy monopolist, ripe for disruption.

"What Ace of Spades is doing is really great because it's so transparent — and because the AP needs competition," said David Nir, the political director of the venerable liberal site Daily Kos, and often the man running @DKElections, another of the core election night feeds. "What the AP does is very opaque and nobody knows what goes on behind the wizard's curtain."

From behind his Fontana desk, Finnigan shares the bipartisan goodwill.

"When you’re dealing with people who really love elections, like we do and they do, partisanship doesn't really matter — you want to report what's going on," he said.

Finnigan traces his start as an unofficial election junkie to 2004. He was an art major at McDaniel College outside Baltimore, a little stoned, watching the results come in — and frustrated as theatrical network anchors "kept holding back" on declaring George W. Bush the victor.

"Once I heard the number of absentees, I was like — there's no reason for [John Kerry] to not concede, he's not going to win," Finnigan recalled.

In 2006, he followed his girlfriend to California for the summer, then decided to stay, landed the truck dispatching job, and dropped out of school. The job gave him ample time to become more politically engaged online, moving to the right from his undergraduate libertarianism to hold strong views not just on lower taxation and less government but also strong opposition to abortion. He's also "extremely libertarian" on drugs and LGBT rights. He found a home on Ace of Spades HQ, a blog devoted in part to heated combat with the liberal and mainstream media. Its founder's sheer obsessive energy has at times put the site in the center of the national conversation, as when Ace (who didn’t respond to a request for his real name, which Finnigan also doesn’t know) caught a strange, quickly deleted tweet by Rep. Anthony Weiner and helped start the chain of events that led to his resignation.

Finnigan started commenting there and emailing Ace in 2007; the founder soon asked him to blog, and he provided obsessive electoral coverage, along with longer apolitical diversions — a piece on living in a haunted house, and a long guide to his other hobby, astronomy.

Finnigan, working weeknights alone in the Fontana office, started the informal "Ace of Spades Headquarters Decision Desk" in 2012, with only the vague approval of Ace. Then, he and a small handful of volunteers began tracking publicly available results of the hottest elections in a Google Doc. They gradually grew more numerous and sophisticated, and this February Finnigan emerged as a major figure in that small, influential Twitter conversation as @AOSHQDD. This summer, his team began to really take on the AP at its own game: not just projecting elections based on public results, but also calling county offices directly to feed the tallies into a spreadsheet.

What followed was an inspiring spectacle: Students, stay-at-home moms, retirees, people battling with cancer and looking for a distraction — a range of members of Ace's conservative community — dove in. There were a dozen volunteers, then 30; now some 130 are "self-assembling" for this November.

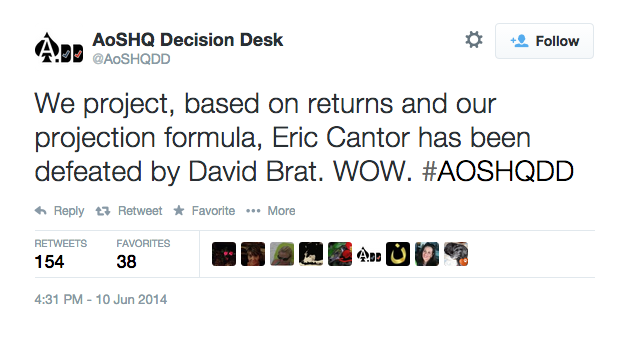

One of those volunteers is Carol Tarasewicz, who is home from her longtime job as controller for a real estate management company with neck pain, "living on painkillers," she said. She'd been listening to the conservative talker Mark Levin, and talked Finnigan into letting her monitor Levin’s hobbyhorse, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor's widely ignored primary. She tracked the county-by-county results obsessively, and frantically emailed Finnigan when Chesterfield County went for his rival, David Brat.

At 6:31 p.m., @AOSHQDD called the race for Brat. AP followed about half an hour later.

And what did Tarasewicz get out of the evening’s work? The thrill, and the distraction.

"It's fun — that was the most exciting night of my life since Scott Brown won in Massachusetts," she said.

The amateurs are still a long way from replacing AP. One major difference is the scale: The AP calls state legislative contests in 50 states, county, and city races in some places, for an expected total of more than 5,000 this year.

Another is the philosophy. The AP believes, for instance, that it has a public trust not to issue its magical call on major races in situations where that could prevent people from turning out for still-competitive down-ballot ones. So this August in Hawaii, where voting was delayed in two storm-damaged precincts for a week, the AP waited a week before calling the Democratic senatorial primary — despite the fact that results from the other precincts made the result a foregone conclusion.

"We don't want to do anything that suppresses voter turnout," said Buzbee.

For Finnigan, who had made the call on election night, calling was a matter of simple math, and of transparency with what was, after all, public data: “There was absolutely no way those districts were going to overturn [Brian] Schatz's lead,” he said.

In the radical transparency of Twitter and the web, there’s also less of a trade-off between speed and accuracy than the AP has. Your readers see the same data you do. If you get it wrong, they see where you’re coming from, and you can correct. And neither Finnegan nor the AP executives pretend there’s more than intelligent analysis, memory, and judgment to figuring out whether a race is really done. Finnigan has, this year, gotten 47 out of 48 right. (The AP got just six of 4,653 calls wrong in 2012, Buzbee.)

If 2004 spurred Finnigan's frustration with the mainstream media mystification, it was 2012 that brought home to him the value to his own movement of aggressive, accurate election results. In the waning days of the 2012 election, many conservatives simply refused to believe public polling suggesting President Obama would easily win reelection. Instead, they resorted to amateur "unskewing" of the polls — removing Democrats from their samples. The plan seemed reasonable; it turned into an embarrassing debacle, evidence to conservatives and their enemies alike of a dangerous detachment from reality that crystallized when Karl Rove, late into the defeat, tried to persuade Fox News not to accept its own analysts' call.

"I wanted to punch my TV set when Rove said 'no,'" said Finnigan. "We knew Florida was doomed about an hour in, and here's a guy who's a supposed expert … That whole mentality of not trusting things and being distrustful of the numbers — no, the polls are what they are, accept that."

American elections have always been, in close races, frighteningly contingent. The machines are rusty, the volunteers are clueless, the voters get confused. And some of what has undermined recent confidence in the machinery of democracy is substantive and irresolvable disputes over voting practices: Did an early call in 2000 send Republicans in the Florida panhandle home? How many Kerry voters were dissuaded by the long lines in Cleveland?

But that lack of confidence also at times misunderstands a system's piecemeal fragility and makes it hard to manipulate on a large scale. And Twitter has played a surprisingly powerful role in nipping what could have easily become perennial conspiracy theories in the bud. This was never clearer than in a high-profile Wisconsin judicial race in 2011, where the Republican clerk of Waukesha County discovered “missing” votes that added 8,000 to the Republican candidate’s margin — something that liberals and conservatives on Twitter argued about, and then agreed on.

“I don't know any serious analyst who thinks that election was stolen,” said Daily Kos’ Nir.

This, too, is a shared partisan interest — there may be few matters of broad national consensus left, but the importance of trustworthy elections is one.

The deep motives that draw Ace of Spades HQ and Daily Kos together, though, remain partisan. Partisans don't just want to enjoy the drama. They want to win. Nir got his start running the Swing State Project, a blog whose aim was in part to demystify polling results and tell liberal Kos readers where to volunteer and where to donate. Daily Kos founder Markos Moulitsas recalled in an email that in his first year blogging, 2002, he got carried away by wishful thinking of a Democratic sweep — and vowed, after that, to maintain a "slavish devotion to data."

"We want to win. Not spin. Win. And in order to do that, you have to look at the real facts, not what you want to happen," said Daily Kos Executive Editor Susan Gardner in an email. "And I would guess that's why Ace of Spaces, on the other side of the aisle, is better than 'objective' news sources."

Finnigan's host, Ace, is less philosophical about the matter. He takes an anarchist approach to his own site, and so Finnigan thanked him, at the time of the relaunch, for “our total indifference and utter lack of influence, encouragement, or inspiration.” Ace responded with the headline, “Local Moron Makes Good.”

Ace said in an email that he had paid little attention to the machine Finnigan was building and tuning, until the night of June 10, when he was having dinner with a friend, who looked up from his phone to report that Cantor had lost. Ace didn't believe it.

"Is that confirmed? Is that from a real source?" he asked.

"It's from your site," the friend replied.

"I was a bit worried, wondering if [Finnigan] had gotten too far ahead of the numbers," Ace recalled. "But as the numbers came in, of course, they confirmed his call."

UPDATE: This story has been updated to make clearer that Ace's remark about Sandra Fluke was intended as parody, in an argument about humor and faux outrage.

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, a fact given by Buzbee was misattributed to another AP official.

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, Sally Buzbee's last name was misspelled.