My mother couldn’t help grinning from ear to ear. She had just cashed in the almost $100 she’d accumulated in two hours by tapping the screen on her phone.

In what’s said to be a millennium-old ritual, Chinese families give out Lucky Money, or “yasuiqian” — a small amount of cash these days presented in a red envelope called a “hongbao” — to their underage and unmarried members at the start of a new year, hoping to ward off bad luck. Though traditionally associated with the New Year, hongbao can also be given out during big events like weddings or a newborn’s first full month.

My mother hadn’t received any hongbao for the Chinese New Year since she got married in 1988 (if we don’t count those given to me but taken away “under her custody”). But this year’s Spring Festival was different.

It was February 9, the second day of the Chinese New Year, when I answered a video call from my mother. She showed me the room, and I realized that all my family members on my father’s side, about 26 of them, were having a big luncheon in the Qilin Palace Restaurant in east Shanghai. It was almost midnight in New York, and I was in my pajamas. Being caught off guard, I muddled through the impromptu new year’s greetings to everybody and hung up. Then my phone started to buzz.

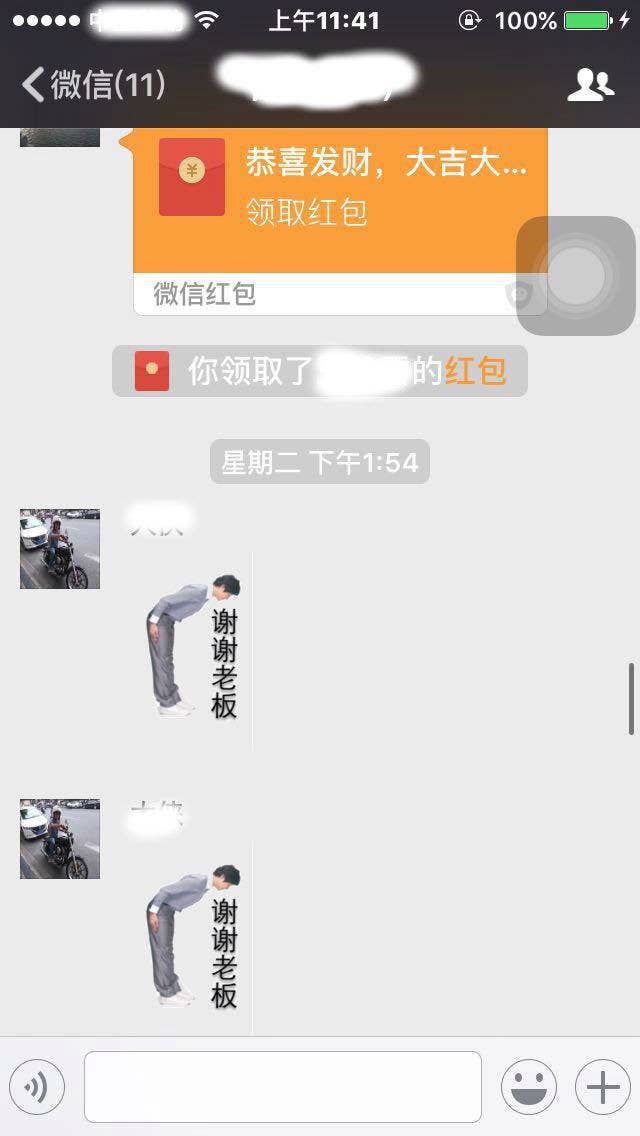

“Thank you bosses,” read a sticker posted by a cousin on our family’s group chat, set up less than a year ago on WeChat, a popular app owned by Chinese internet giant Tencent. He was suggesting other members of the family drop “red packets” – a function that enables users to transfer a small amount of money, up to 200 yuan (about $31) to multiple users or groups.

The dishes were almost finished when my mother called and normally it would be the time for toasts — I remember vividly the pressure to go around each table and say something nice to everyone: “I hope you get admitted into a good high school” to a niece; “I wish for you to have a white and chubby little girl next year” to the newlyweds.

WeChat’s Red Envelope function crushed the toasts this year. The rules were simple: a number of red envelopes with different amounts inside were created using the “random amount” feature — one contains the highest amount, and the faster you tap the game’s “open” button, the higher chance you’ll get one of the bigger payouts. Not physically being there put me at a disadvantage: When somebody dropped a red packet, I couldn’t hear the cue, and all the envelopes were gone within seconds — often before I even realized the game had started. A huge flood of messages poured in, most of them notifying me that another red envelope had been opened.

My mother recalled the frenzy over the phone to me later: “Your rich aunt was very into the game that day — she snatched as hard as I did just for cents!”

This year, collecting virtual hongbao has become a common scene across China. From Lunar New Year’s Eve to the 15th day of the new year, which usually marks the end of the Spring Festival celebration, families, friends, colleagues in hundreds of thousands of homes, restaurants, and workplaces adopted the new custom. What was once an ancient ritual is going through drastic changes: Anyone of any age from anywhere in the country can exchange a red envelope, as long as they have a smartphone.

The scale is almost unimaginable. On the Lunar New Year’s Eve alone, 420 million users — almost a third of the nation’s population — reportedly swapped 8.08 billion digital envelopes on WeChat, eight times more than last year. The peak came just after midnight, with 2.4 million hongbao being sent and 6.2 million being opened simultaneously. Just six days into the new year, that number had grown to 32 billion red envelopes transferred.

This year, WeChat also introduced a new function that was available for only eight hours. It allowed users to post a blurred photo that others had pay with a tiny red envelope to view. Twenty-nine million photos were posted and 192 million people paid to view them.

Following Tencent’s success in the red envelope game, China’s two other major internet companies — Baidu and Alibaba — are trying to play catchup. Alibaba’s online payment product, Alipay, spent about $41 million to replace Tencent as the exclusive sponsor of state-owned CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala this year, which reached 690 million viewers. The company claims 100 million users exchanged about 800 million red envelopes via its app during the show, and that it collaborated with 45 sponsors to give away 800 million yuan (about $122 million) to users who played the interactive games — the game required one to shake their phone and collect e-cards according to the instructions on the TV screen. At the same time, Baidu said it gave away $644 million in coupons and $46 million in cash through Baidu Wallet, its online payment system.

“Distracted for just a few minutes, I might have missed a couple billion yuan,” a newly popular saying goes.

The goal for these companies is simple: to keep as many users as possible and be the dominant platform for all of China’s needs.

“Two of the best things of the Spring Festival are long vacation and red envelopes,” read a widespread post on Weibo.

Yet the concept of sending virtual red envelopes is very young. In 2014, WeChat introduced its new hongbao function and was able to get 8 million users to link their debit card information with their WeChat accounts. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s founder, compared WeChat’s launch of digital red envelopes to “a sneak raid on Pearl Harbor” — it took Alibaba’s Alipay years to achieve that goal.

An average person in China spends 40 minutes per day on WeChat, so for it to break into the mobile payment market was a significant achievement. WeChat got another huge boost that year when it became the sponsor of the Spring Festival TV gala show, or “Chunwan,” gaining nationwide exposure and a semi-official endorsement.

The idea of digital red envelopes became so popular that even the country’s ruling Communist Party joined the bandwagon, giving away $50,000 on three consecutive days — the party used Alipay, which has an optional password feature within its red envelope program. Each day the WeChat account “Communist Party Members,” run by the state Xinhua News Agency, announced the password of the day. "You will earn what you worked for," it said, followed by “As long as we persevere, dreams will come true" — both pulled from President Xi Jinping's 2016 New Year speech. The prizes were reportedly all gone seconds after the password was released. Alibaba claimed that the source of the money "had nothing to do with party membership dues" and was instead "raised by Xinhua's website and Alipay on their own," according to the AFP.

All this begs the question, “What makes this game so addictive?”

It could be that sending red envelopes works as an efficient way to “check in” with one’s social network. Under WeChat’s rules, a person can bundle at most 100 envelopes in each packet with no minimum amount inside. So it’s possible for you to only give out one dollar to multiple groups, which according to the Chinese-language Hong Kong news website The Initium lets users “feel your presence and you feel like a king when others send you emojis of a person kneeling and showing appreciation.”

“Other people who miss the red envelope will never know how much you actually put inside, so you remind people of you without actually spending a lot,” a friend of mine told me during a hot pot gathering when I was in China in January.

But one of the most popular explanations behind the psychology of digital envelopes was posted on China's Quora-like site, Zhihu.

“Exchanging red envelopes (physically or virtually) is never an economic behavior, it’s a social behavior,” wrote Li Songwei, a researcher at Beijing’s prestigious Qinghua University.

“[A red envelope] gives serious verification to interpersonal connection: ‘see, this is real money! Even though we might not be close, I really treat you seriously!’...The act is a confirmation for both sides, ‘we have a real connection, I’m not alone,’” he explained.

“The virtual connection now needs some hardcore verification, too,” he concludes, “at any time, human beings long for deeper connection with others. On the internet, we can’t experience physical presence, exchange eye contact, express our concerns, all we have is this lifeless data. So let’s make the data more sincere. Finally, we found data that might be the warmest: money. It doesn’t matter if it’s a penny or not, the thing that matters is that it is real, our interactions are real.”

But the virtual red envelope obsession can also turn into lunacy, according to users. Following the game’s popularity, many people on Weibo have reported that their elderly family members indulge in the game day and night, sometimes even skipping meals and sleep.

“My parents went next door to the neighbor’s and just sat on their couch for an hour tapping their own phones."

“It’s totally nuts in China," a friend told me during a recent conversation on WeChat. "My parents went next door to the neighbor’s and just sat on their couch for an hour tapping their own phones. Fortunately, that was a really close neighbor."

As the game’s popularity has soared, companies have introduced a number of external tools to make to make collecting virtual hongbao more convenient. Tencent officially released a tool called “red envelope alarm clock” shortly before the Chinese New Year, which allows auto-monitoring and sends reminders that users receive throughout WeChat, Alipay, and Weibo. Alibaba also released a similar tool. Countless third-party apps now allow addicted users to skip having to unlock their phone.

But alongside that stratospheric rise, a dark side has emerged. Phishing and scams have become rampant and, in extreme cases, the game lends itself to blatant gambling. According to Xinhua, Tencent closed 100,000 accounts that were engaged in gambling just in the last year. Last August, 300 gamblers from Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong Province were arrested as part of a bust involving 10 million yuan ($1.53 million). The organizers of the WeChat “casinos” set up groups specifically for the purpose of professional gambling, published QR codes to enter and invited players to join. Games such as baccarat, Chinese casino game sic bo, and even solitaire are now “red-envelopized,” with the organizers taking commissions from the winnings. The only difference between a family-friendly red envelope game and gambling sometimes lies in the motivation of the participants.

But, like most addicts, people justify their hongbao fever any way they can. The Chinese holiday was once about the lively noise of crowds, shopkeepers yelling about sales, and shoving your way into the temple to be the first in line for the incense, but all this has now been replaced with the repeated buzz of phones. And with the likely disappearance of fireworks from the sky, it is likely that next year’s spending on red envelopes will be even higher. As my mother told me after the family luncheon, “Snatching red envelopes is the new fun; we are just spending the money we saved from fireworks.”