Researchers have definitively traced how HIV first spread to the US, thanks to an impressive genetic analysis of thousands of blood samples collected in San Francisco and New York in the late 1970s.

The study, published on Wednesday in Nature, focused in particular on decoding the viral strains carried by eight people who were infected with HIV. Because the virus mutates rapidly from one person to the next, it’s possible for scientists to compare genetic markers in each strain to track the history of how it spread.

These eight new genetic sequences, along with a ninth from sub-Saharan Africa that had been done years earlier, are the oldest full copies of the HIV genome.

“Looking at these archival samples allowed us to step back in time,” Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona and lead author of the study, told BuzzFeed News.

Worobey’s analysis shows that after emerging in sub-Saharan Africa in the early 1900s, HIV hit the Caribbean by 1967, and made its way to New York City around 1971. Within about five years, it then spread to San Francisco.

Exactly how the virus traveled from the Caribbean to the US remains unclear.

“There’s many plausible routes that the virus could have taken,” Worobey said. “It could be a person of any nationality moving from one region to the next. It could have been a contaminated blood product, since until the mid-1970s a lot of commercial blood products were imported to the US from Haiti. We simply don’t know.”

The paper is a technical feat, but also has a powerful human side: It definitively clears the name of “Patient Zero,” a gay French-Canadian flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas who for decades has been accused of bringing the virus to North America.

Dugas was hired by Air Canada in 1974, and his job took him to dozens of cities across North America. In 1980, he was diagnosed with skin cancer, just a year before the Centers for Disease Control flagged a mysterious cluster of infectious diseases in five young and previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles.

By 1982, the CDC had identified the mysterious illness as AIDS. Although tens of thousands had been infected by that time, scientists struggled to figure out what was spreading and how it was being spread. The CDC’s study of the initial cluster study grew to include 40 cases in several cities, displayed in CDC papers published in 1984 as a ball-and-stick diagram showing how they were connected by sexual encounters.

Dugas, known simply as Patient “O” (for “Outside of California”) in the CDC papers, was near the center of the cluster. A mistake in CDC communications, however, labeled him as Patient “0.”

Dugas died that same year, but the mistake would plague his name posthumously. In 1987, Randy Shilts published the widely read And the Band Played On, the first popular history of the AIDS epidemic. In it, Shilts named Dugas and delved deep into his life, portraying him as “Patient Zero,” a sexually promiscuous flight attendant who knowingly spread the virus.

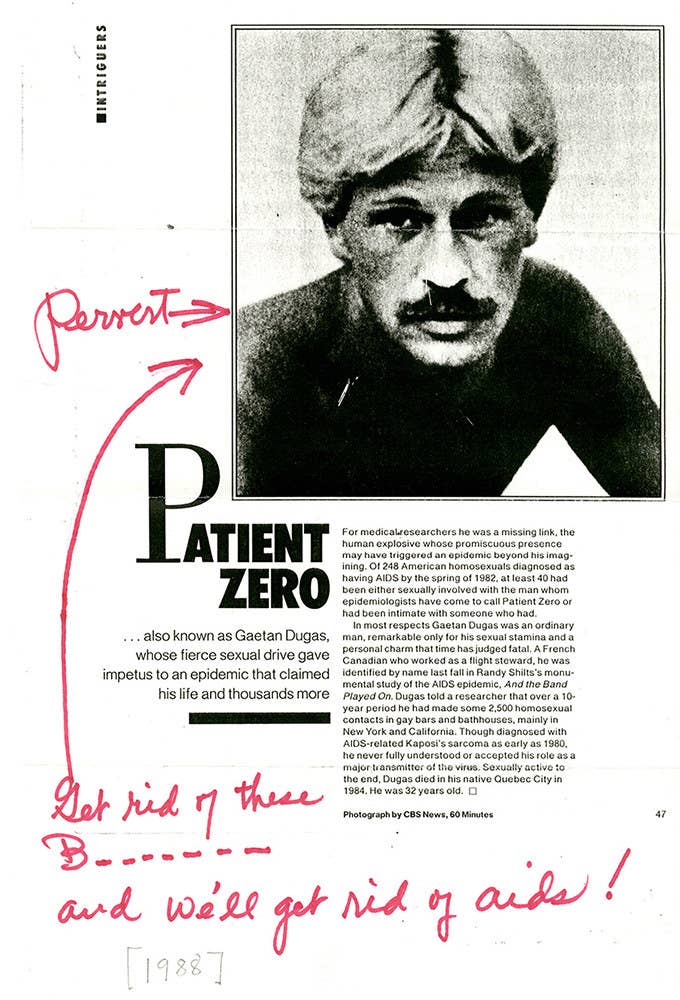

The book spurred many sensational takes about the highly feared and poorly understood epidemic. The New York Post ran a front page headline that read, “THE MAN WHO GAVE US AIDS,” claiming that Dugas had triggered a “gay cancer” epidemic in the US. The National Review nicknamed Dugas “the Columbus of AIDS.” People magazine declared Dugas one of “The 25 Most Intriguing People of ’87,” writing that his “fierce sexual drive gave impetus to an epidemic that claimed his life and thousands more.”

AIDS activists as well as scientists at the CDC tried to make the public aware that the label was untrue.

“We spent a lot of time denying that and refuting that, but some people kept on believing it,” said Jim Curran, an epidemiology professor at Emory University who led the CDC task force on AIDS in 1981. Although “Patient 0” had become the agency’s shorthand for Dugas after the mistake was popularized, he said, they never claimed he was the first case in the US.

While scientists struggled to work out the mechanics of the virus, the accidental phrase “Patient Zero” — never before used to describe the first case of any epidemic — took hold in the public’s imagination.

“There was so much anxiety and fear about HIV and origins of HIV that it led to blame — blame along people’s beliefs, blame along people’s prejudices,” Richard Elion, an HIV researcher at George Washington University, told BuzzFeed News. “People want to believe that bad things in the world happen because of bad people. But biology doesn’t work that way.”

Worobey’s new study goes a long way toward dispelling the myth of Patient Zero. In addition to the eight genomes that showed the virus’s movement from the Caribbean to the US, the researchers sequenced Dugas’s viral genome and showed that it was typical of other US strains at the time. In other words, the virus he carried had no markers distinguishing it as an earlier strain.

"People want to believe that bad things in the world happen because of bad people. But biology doesn’t work that way."

For the activists and scientists who have been trying to clear Patient Zero’s name for decades, the fact that the myth persisted for so long should serve as a warning.

“Patient Zero sort of served as a gay boogie man,” Mark Harrington, executive director of the Treatment Action Group and a longtime activist, told BuzzFeed News. “We still see that — certain people are still portrayed as predators for transmitting AIDS to partners. We need to do a better job of distinguishing diseases from villains.”

There may be scientific value in figuring out the “Patient Zero” of any disease, such as understanding what enables viruses to spread or what gives certain people the ability to fight infections. But Worobey hopes his study will help prevent future cases of finger-pointing.

“I think for any infectious disease — whether it’s Zika or Ebola or SARS or flu or HIV — there is value in trying to understand what it takes to make a successful outbreak,” he said. But, he added, “the idea of blaming people for a pathogen that infected thousands of people before anyone knew about it is absurd.”