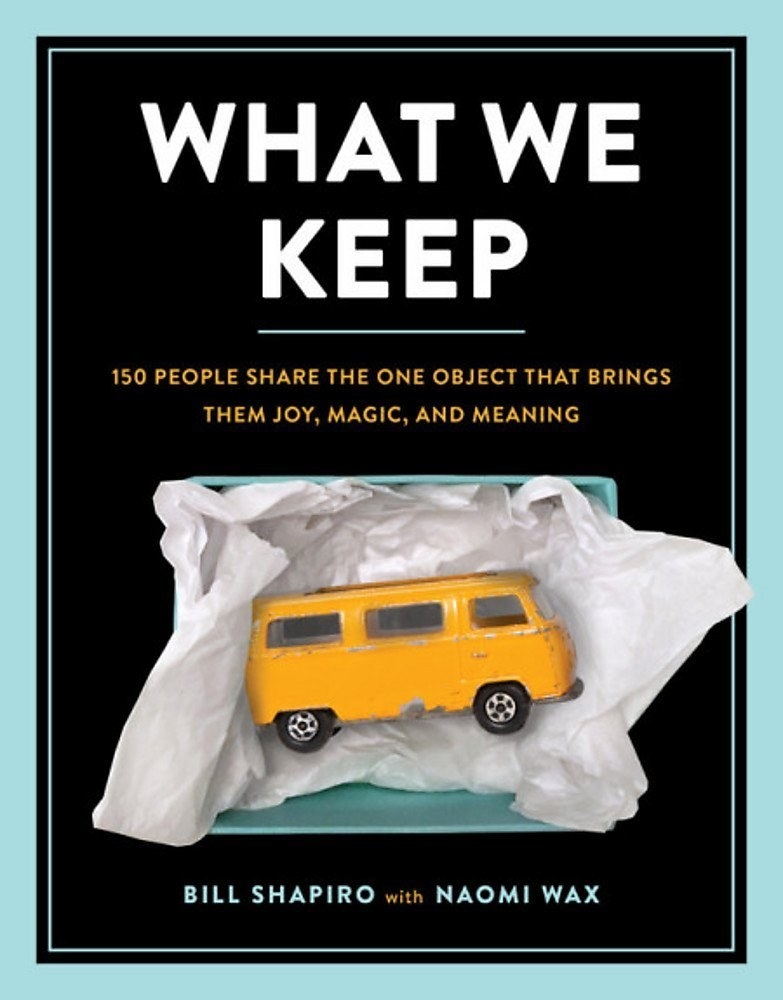

In What We Keep, author Bill Shapiro collects talks to all sorts of people — writers, TV hosts, nuns, teachers, entrepreneurs — about the seemingly ordinary objects they've held on to all their lives. Below are some of our favorites.

Janet Mock, author and activist: Copy of Their Eyes Were Watching God

This is my holy text. It’s the same copy I read in 11th-grade English class. I was one of two black kids in my entire high school, and reading Their Eyes Were Watching God was the first time I’d felt deeply seen. It’s a book about a black woman’s journey to self-revelation and love, and it made me think it was possible, in some world, some years down the road, that I would be able to write my own journey of self-discovery and love.

When I was 16-and-a-half, the text was all about the romance, you know, all about the love, but every time I returned to it, there were different layers. I realized later that there were feminist layers, racial layers, the way she’s growing into becoming a writer, the way she invented her own language sometimes, writing the way her people spoke.

It’s been with me on so many levels. As a trans woman, the disclosure piece — in telling your story to someone you care about, someone you hope to have a relationship with — is fraught with all kinds of anxiety and fear and potential loss. So when I wrote my first book, Redefining Realness, I stole Hurston’s structure, which opens up in present-day with a woman telling her story to someone she deeply cares about.

I actually began my wedding vows to Aaron with words from this book: “He looked like the love thoughts of women.” When I was younger, I was lovesick even though I had no experience with romance or anything, but the first time I read these words, I remember saying to myself, “Oh my god, I want somebody who looks like the love thoughts of women!”

It’s the book that has been on every single bookshelf I’ve ever had since the 11th grade. Now, it’s on the desk where I write. It’s the book that I turn to.

Carla Hayden, 14th Librarian of Congress: Handmade ceramic cup

We were living in New York in the late ’50s and my mom started working with the Housing Department, helping out with after-school youth programs in the Bronx. One of the crafts projects she led had the kids making ceramic cups with faces on them. My mom brought one home for me. When you’re a kid — and I was six or seven at the time — you get a little jealous when your parent is doing stuff with other children, so this was important to me. But there was something else: She had painted the face brown because I was brown, with a little curl in the middle of the forehead. That the cup looked like me — it was one of the earliest things I had with a brown face — well, that was something. It became my favorite cup, and evolved into my favorite pencil holder and, later, into my favorite holder for makeup brushes and pins. It’s been on my dressing table for years. It’s still there.

Renee Langvardt, owner, Java Junkies café: Nesting dolls

I purchased these nesting dolls on a street in Novosibirsk, Siberia. I was on a missionary trip just after I graduated high school, and that’s where I realized my purpose. I was walking down the street and the people there were so beautiful that I suddenly realized that everybody, no matter where they are in this world, needs love — not in a Coca-Cola slogan kind of way. But I knew then that the grace that’s been shown to me by Jesus was something I wanted to pass on to others, that I wanted them to feel loved and feel important and that they have a purpose. That’s become my mission and passion. These dolls represent more than a time in my life; they embody how things fit together for me and a lot of my why.

Cheryl Strayed, author: Murex shell

This has always been an object of wonder for me, but I’ve never talked to anyone about it. Even my husband didn’t know the story — and we’ve been together 20 years.

The first week of first or second grade, we were asked to bring something in for show-and-tell. I walked around our tiny apartment in Chaska, Minnesota — by then my parents had divorced, my mom was a single mom with three kids, we were poor — and we didn’t have anything interesting or cool for show-and-tell.

I decided I’d bring this murex shell. It was given to my mom by her father, who was in the army in the Philippines in the ’40s and ’50s. It was spiny and glorious. It had an air of mystery. But there was one problem: I wanted to say that I’d found it on an exotic beach. That’s what I wanted people to think. For my story to work, though, I would have to separate the poufy red velvet pincushion part — which was glued into the crevice — from the shell. I used a butter knife, and I can still see where I made some progress. My mother came upon me and told me I couldn’t do that. She said, “You can take the shell — but as it is, like a pincushion.” I remember thinking that that ruined everything. I wanted so badly for people to think I’d found this shell. I was in tears. I was obliterated. And I didn’t bring it.

The shame about being poor goes all the way back, and having a glorious shell was the opposite of that. You know, there’s what you remember now but also what you remember imagining then, and I remember that even then I had this image of myself as the kind of girl who would be walking on an exotic beach, who would find a magnificent shell like this. It was not only that I was there but that I found the shell. I wanted to be lucky. It was also about beauty, about the ambition to be venturing out in the world and in a far-off place. What I knew was that I wanted to be something that I wasn’t, that I wanted people to see me as someone who I wasn’t. I’ve come to realize that it wasn’t that I wanted to deceive but that I wanted to become.

The shell pincushion now sits on a shelf in my bedroom. Looking at it, knowing I had those thoughts of who I wanted to be and what kind of life I wanted to live, and knowing that I’ve done it, is the most beautiful, the truest thing. It’s the core of who I am. The shell is like this present: It holds in its very being both the girl I was and the woman I became.

Bobak Ferdowsi, systems engineer, Mars Curiosity rover: Lego Mars Rover

I worked on the Mars rover for nine years and then there I was sitting down on the rug in my apartment, emptying out all the pieces and building it. I remember feeling unrestrained happiness: I’ve done something that merited a Lego set!

I grew up on Lego. If there was a way to go back in time and show the childhood me that the adult me inspired a Lego toy? I mean, I might be like, “Whatever, old man.” But I don’t think so.

Jenifer Fox, founding head of the Delta School: Bunny tea cup

Before my mother had her first schizophrenic breakdown, I remember our family being happy. My mother made a big deal out of holidays, especially the decorations, and we always had dinner together. A lot of good memories.

And then it all disappeared.

I was eight or nine when my mom got sick, and a lot of her illness was expressed as a weird jealousy of me. She would do things like give my brothers birthday parties but not me. Around this time, my father stopped coming home for dinner. My mother would prepare dinner, then we’d wait for him while she paced around, crying.

I remember she had a china chest, and I’d stand there looking at this cup with this happy bunny family on it. Every so often I’d say, “Can I touch it?” and she’d take it out and let me hold it for a little while. Then she’d put it back. Even then, I guess I could feel that something was slipping away.

After college, I was getting ready to go overseas and she said, “Here, you can have this.” She gave it to me and said, “Go off and live your life.”

I took it with me to Turkey, where I taught English, and later to Kenya. The cup to me represented my freedom, and it really launched me into my sort of peripatetic life — and my ability to keep moving when things fell apart. When my marriages ended, it’s the one thing I held on to. I’ve lived in at least 20 different places, and it’s been all over the world with me, this piece of china. It’s a sweet little cup, but it holds a lot: It’s both a reminder of what was lost and a symbol of my independence from my mom and from her illness. It’s the only thing she’s ever given me — and it’s the one thing I’d always wanted.

Carter Roberts, president and CEO of World Wildlife Fund: Wood paddle

This paddle was given to me in Mozambique by a local fisherman, an older gentleman with a weathered face who you could tell had spent his life on the ocean. He lives in one of the poorest areas of the world, where they depend on fishing for food. Foreign trawlers had cleaned out the local fisheries, and we’d been working for about 10 years to give local communities more control. Now they’re catching larger fish and they’re able to feed their families.

It’s not the most elegant paddle I’ve seen, but every part of it tells a story. The handle is broken in half but instead of getting a new one, the fisherman nailed it together because deforestation has made wood so scarce. On one side of the blade, there’s an etched set of lines. Like a checkerboard. He told me that during the years when the fisheries were cleaned out, the fishermen would pass the time by playing a board game on the blade. I keep the paddle by my desk. It reminds me of what’s at stake if we don’t care for the land and the ocean.

Elana Haviv, founder and executive director of Generation Human Rights: Stuffed bear

We made these bears in second grade. I clearly remember arguing with my teacher that I needed to sew up her stomach, while my teacher insisted that I leave it open so I could put treasures inside. Why would I put treasures inside a hole filled with stuffing? My teacher won the battle and the bear’s stomach is still open, but I’ve never once put anything inside it.

As an adult, I’ve spent long periods working with refugee children in Bosnia and other war-torn regions. They’ve lost so much, including the ability to have a say in most aspects of their lives. That always hits me when I come home and my treasure chest bear is lying on my pillow, empty.

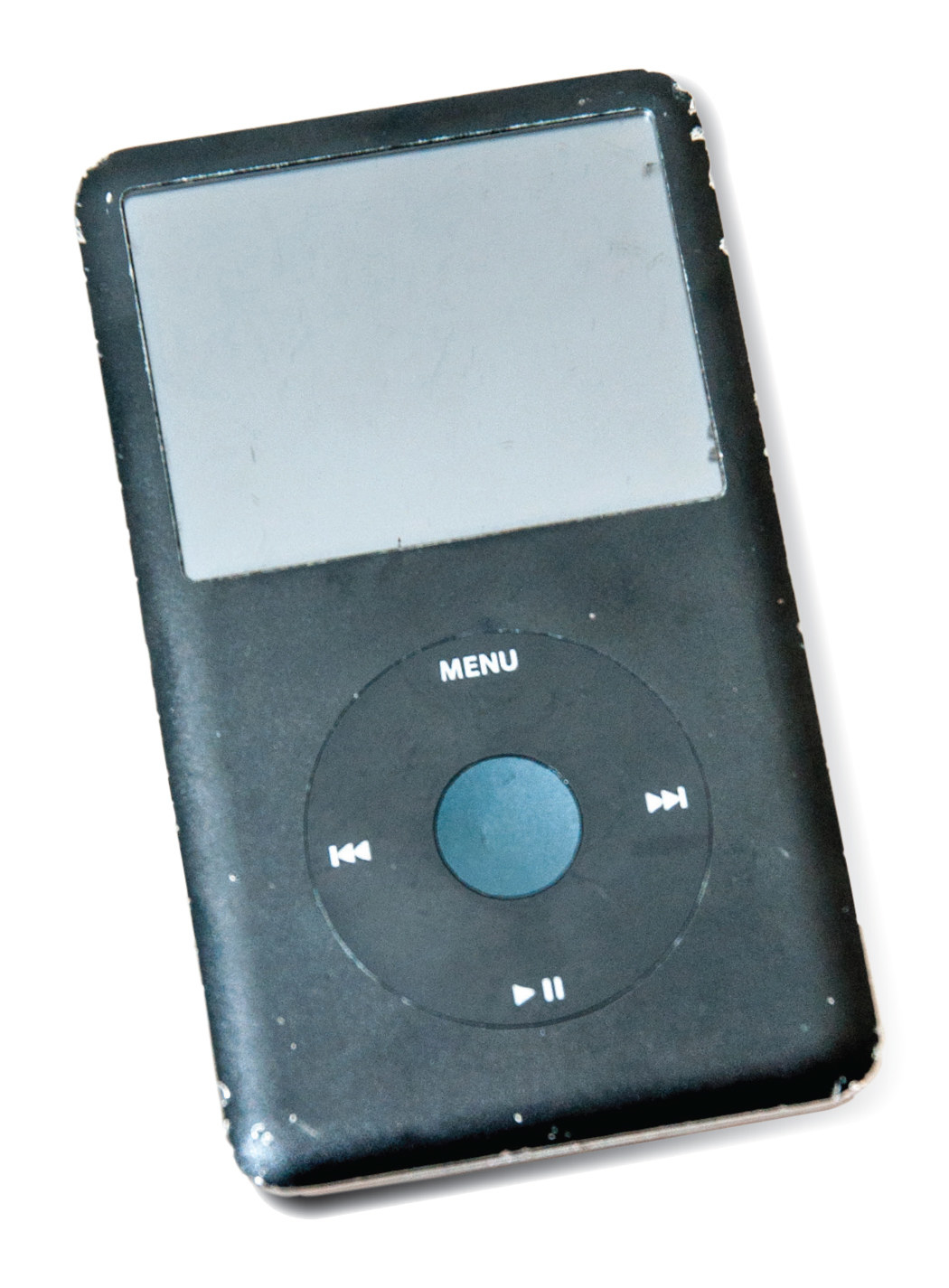

Kaija Mistral Towner, hair and makeup artist: iPod

I keep this iPod in the glove compartment of my car. A lot of what’s on it are playlists and photos from my first real relationship, my first true love. He and I bought an RV and took a six-week road trip from Seattle to Colorado, then through Texas, Tennessee, the Carolinas. I listen to the playlists when I’m alone and have a long drive; that’s when I get sentimental — you know, when you want to wallow in your memories? I’ll remember what part of the drive we were on when we first heard a particular song. That was 12 years ago. Now I see him every six months or so, but we’re so different. I think about who I was then and who I am now. Was I okay living the rest of my life arguing? Would I be okay now with less passion but more stability? I’ve never backed up my iPod. There’s part of me that feels like when it dies, it wants to be gone, that I should find new music, that it’s time.

All images and text excerpted from What We Keep by Bill Shapiro with permission from Running Press.

What We Keep is out now.