A trove of new documents from the investigation into Prince's death offer a detailed picture into the rock star's final days, revealing how, with the help of his friends, Prince fiercely protected his privacy, and how those close to him scrambled to get him help after realizing the extent of his opioid addiction in the last week of his life.

The records — comprised of 10 gigabytes of documents, photos, and videos from a two-year investigation — were released this week following the announcement Thursday that authorities will not file criminal charges over Prince's death.

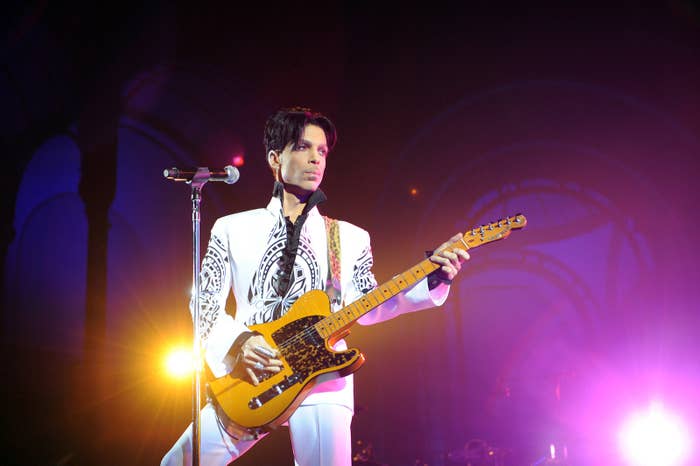

The legendary pop music pioneer died on April 21, 2016, at his Paisley Park estate in Minnesota after taking counterfeit painkillers that contained the powerful opioid fentanyl.

"The bottom line is we simply do not have enough evidence to charge anyone with a crime regarding Prince’s death," Carver County Attorney Mark Metz said in a press conference Thursday announcing that no one would face charges.

Metz explained that Prince had been taking counterfeit Vicodin pills that were laced with fentanyl, but said there was no evidence that the 57-year-old had any idea that the pills contained a drug that is 30 to 40 times stronger than heroin. A toxicology report after his death found an "exceedingly high" level of the opioid fentanyl in his body.

“In all likelihood, Prince had no idea he was taking a counterfeit pill that could kill him," Metz said.

Authorities found "a lot of pill bottles" at Paisley Park, including dozens in his dressing room and nightstand. The musician was long known to suffer pain from injuries relating to performing and to take painkillers for them.

"Prince had no known Vicodin or fentanyl prescription," said Metz. He added that despite a two-year investigation, authorities had no knowledge of how or where Prince was getting the counterfeit pills.

"I cannot factor Prince’s celebrity status and tremendous fame into the charging decision. The charging decision must be biased on the legal merits," said Metz.

The documents released by the Carver County Sheriff's Office from their investigation show the musician was a very private person who was intensely protected his friends. And those closest to Prince told authorities they didn't know about his s addiction to painkillers until the final weeks of his life when they rushed to save him.

Kirk Johnson, Prince's bodyguard, claimed that it wasn't until the star's jet was forced to make an emergency landing in Moline, Illinois, on April 15, six days before his death, that he learned Prince was using Vicodin, according to the documents.

Prince was unresponsive when Johnson carried him out of the plane and onto the tarmac, where paramedics administered Narcan, a medication used to treat overdoses in an emergency situation.

The paramedic, Justin Fredericksen, told investigators he initially administered 2 milligrams of Narcan "which seemed pretty ineffective." That was surprising, Fredericksen said, because even heavier opiate users typically wake up after one dose.

"Fredericksen said it wasn’t long after the second dose of 2mg of Narcan that Prince took a large gasp and woke up," Carver County Sheriff's Detective Chris Wagner wrote in a report.

The paramedic then asked Prince how he was feeling and without the musician saying a word, Johnson replied, "Prince feels fine."

And when he arrived at the hospital that night, Prince refused to submit blood for testing and declined any other medical tests, a nurse who treated him told investigators. Johnson told officials that Prince refused to provide a blood test at the hospital because he did not want people to know about his use of prescription medications.

On April 20, the day before he died, Prince spoke with his doctor, Michael Schulenberg, and told him he was "feeling antsy" and asked questions about opioid withdrawal. That evening, after speaking with his doctor, his management team made contact with a drug addiction program.

Schulenberg, who is accused of illegally prescribing Prince an opioid a week before the musician died, will pay $30,000 in a settlement for a federal court case over the prescription, the US Attorney's office announced on Thursday. The doctor prescribed Percocet to Prince on April 14, but wrote the prescription to Johnson as a way to maintain Prince's privacy.

Writing a prescription for a fake name is a violation of the Controlled Substances Act. But the drug Schulenberg prescribed does not contain fentanyl and did not cause Prince's death, officials determined.

Documents from the US Attorney's office clarify that Schulenberg is not under any criminal investigation. "Doctors are trusted medical professionals and, in the midst of our opioid crisis, they must be part of the solution,” US Attorney Greg Brooker said in a statement released Thursday, announcing the $30,000 civil settlement.

"As licensed professionals, doctors are held to a high level of accountability in their prescribing practices, especially when it comes to highly addictive painkillers. The U.S. Attorney’s Office and the DEA will not hesitate to take action against healthcare providers who fail to comply with the Controlled Substances Act. We are committed to using every available tool to stem the tide of opioid abuse," Brooker said.

Also on Thursday, Sen. Amy Klobuchar spoke on the Senate floor about Prince, in honor of the upcoming anniversary of his death.

"For Minnesotans, Prince was a superstar next door," she said. "On Saturday, that anniversary, purple will rain again."