Open up Twitter's live-streaming app Periscope and you'll quickly find yourself hopping in and out of life all over the globe. One tap, and you're in a living room in Kansas City, where the latest Republican debate is on. Another, and you're on campus at a Russian university, watching students pass by on the way to class. One more takes you into the streets of Santiago, Chile, where residents have flooded the streets immediately following an earthquake.

On a map Periscope built as a portal into these active streams, two countries consistently show up with very big numbers. The first, understandably, is the United States of America, the home of Periscope, and a country with a large, connected population. The second, perhaps surprisingly, is Turkey — which, even at 3 a.m. Istanbul time, when this story is being written, is still buzzing with activity, with more streams broadcasting live than any country outside the U.S.

The past-midnight Turkish live-streaming is no anomaly. The country seems to always be Periscoping, an assertion that's backed up by the numbers. Turkey is the second most active country in terms of Periscope streams, according to social analytics company Sysomos. And three of its cities — Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir — are among the top 10 cities with the most Periscope users, according to Twitter.

"It's definitely top five across any metric you look at," Kayvon Beykpour, CEO of Periscope, told BuzzFeed News in an interview on the rooftop of Periscope's San Francisco headquarters. "I'm impressed that it struck a chord to the extent that it has."

Impressed yes, but perhaps not surprised. As Beykpour knows well, Periscope and Turkey will be forever linked. The concept for the app came to Beykpour as he planned a visit to the country, and the circumstances that led to the idea's generation are deeply linked to its popularity there.

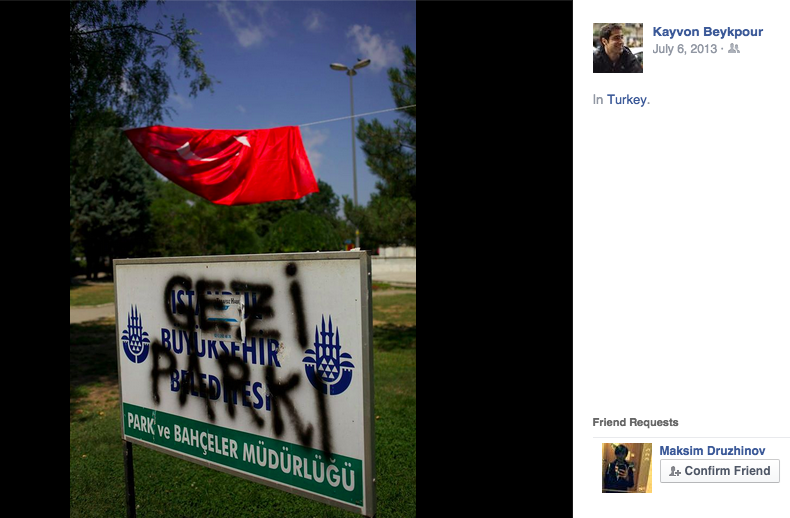

Gaze Into Gezi

A little over two years ago, Beykpour was an entrepreneur in transition, on leave and traveling the world, when a planned visit to Turkey became suddenly complicated. About a month before he was set to touch down in Istanbul, chaos descended on the city's streets — or as Beykpour put it, "shit started erupting."

It was the spring of 2013 and Turkey was entering a period of intense civil unrest. The country's prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and his ruling Justice and Development Party were already seen as an overreaching bunch when they tried to turn an Istanbul park called Gezi into a shopping mall. After a group of protesters were teargassed while trying to save Gezi, people from all walks of life in Turkey took to the streets in protest. The government responded with force, deploying police armed with tanks, tear gas guns, and water cannons to battle the thousands of protesters. And Beykpour began to reconsider his visit.

"I was like, 'OK, I really want to go, but is it safe for me to go? What exactly is going on?'" he said.

So Beykpour did what anyone would at the time; he turned on CNN and checked social media looking for a glimpse into the streets of Turkey. But what he saw was of little use. "I got this very dramatized account of what's happening through traditional media, even on Twitter," he said.

What Beykpour wanted was a live window into the action on the streets, particularly the one on which his hostel was located. "That would be literally a perfect picture for me of whether the violence is concentrated elsewhere or whether shit's crazy and I shouldn't go," he said. Such a window wasn't available at the time. But given the breadth and reach of the mobile internet, it was clearly possible to create it. "There are thousands of people with high-speed network connections and smartphones in their pockets who walk by that street every day. Why isn't there some marketplace where I can negotiate that demand?" he recalled thinking at the time.

In the end, Beykpour made the trip, and walked away from it with the idea for what would eventually become Periscope, the company he later sold to Twitter.

"That was the initial use case," Beykpour said. "It was, I want to see what's happening in this street in Istanbul or at Gezi Park."

The Periscope Country

If Beykpour was disappointed with what he saw on CNN during the Gezi protests, many people within Turkey were likely even more so. The mainstream media in the country largely ignored the protest movement. During one heated point during the clashes, CNN Turkey aired a documentary about penguins instead of protest coverage.

Free speech in Turkey has always been a thorny issue. The original version of Article 301 of the country's penal code made it illegal to "insult Turkishness." The article has since been amended to a less toothy version, but the threat of its use still loomed for those considering a challenge to power. Meanwhile, the implicit threat of large fines from the government ensured that TV stations kept their coverage of the Gezi protests tepid.

This isn't to say free speech doesn't exist in Turkey. Actually, anything but. Almost as soon as the internet became capable of supporting them, people in Turkey created social platforms to share ideas and news that otherwise may have been suppressed. In 1999, for instance, a Turkish developer named Sedat Kapanoglu built Eksi Sozluk, or "Sour Dictionary," a user-generated "dictionary" that instead of defining words posted news events, cultural memes, and other random topics and allowed anyone to anonymously post "definitions," or thoughts about these terms.

Eksi Sozluk, and the copycats that followed, essentially created trending topics before there were Trending Topics. The behaviors learned on them made Facebook and Twitter easier to understand when they debuted, so Turkey quickly became one of the world's most significant adopters of social media.

"When you give Facebook or Twitter to such a community, they already had [something similar] in 1999," said Ismail Postalcioglu, a social media professional, in an interview in Istanbul the month before the Gezi protests. "This is just a newer version."

Reached via email, Kapanoglu pointed to the popularity of reality television in Turkey as a main reason for Periscope's ascent there. "People love to watch other people's lives and discuss them," he said. "No wonder they are interested in Periscope's natural, unedited, reality-show-like content."

No doubt that's part of the appeal. That said, it's hard to discount a population's affinity for an amateur broadcasting tool like Periscope when its professional broadcasting companies tend to stand down during critical moments. Yalkin Yel, a marketing executive who protested in Gezi Park during the clashes, expressed as much in an email. "These days there is not so much protest or something like it but everybody knows if it happens we all gonna need," he said. "The fear of not to be able to make yourself understood pushes people to find different solutions. Like Periscope."