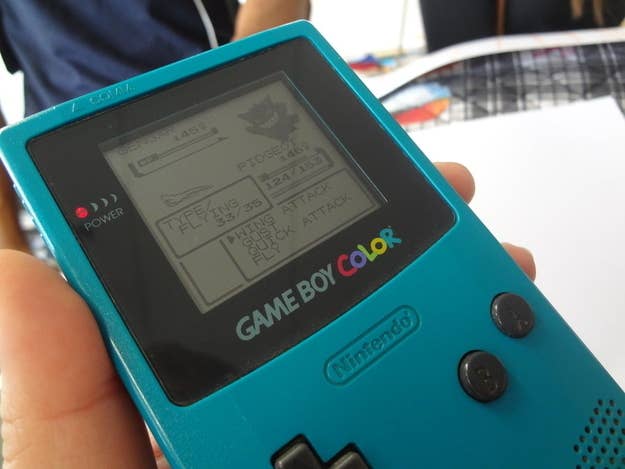

I was an obsessive kid. I liked to collect and catalog everything from coins to yarn to dollhouse miniatures, and I used to carry around a canvas bag filled with fantasy books so that when I finished one, I'd have plenty of options for the next. I was, in my way, a little bit lonely. But then when I turned 10 I got a Game Boy Color, and Pokémon Blue, and I found my place.

Pokémon, with its gotta-catch-'em-all ethos, fit perfectly with my desire to build tiny, orderly worlds of my own. I dutifully collected all 151 original Pokémon that year, haggling with my little brother and next-door neighbor to trade me ones I couldn't catch myself. My first Pokémon was a Bulbasaur, a smiling beast with a giant, onion-like bulb on his back. I named him Sprout, and I regarded him the way I used to think about my favorite stuffed animals: just south of real, but alive enough to feel like a companion.

Long after my brother stopped playing, opting instead for big-budget fantasies like Skyrim and Grand Theft Auto, I kept collecting. I'd stop for months, even years at a time, but I would eventually play at least one of every generation of Pokémon. There was Pokémon Yellow (1999), modeled closely on the TV show I used to wake up at 6 a.m. on school days to watch; Pokémon Crystal (2001), the first time you could finally, finally choose to play as a girl; there was Gold and Black and SoulSilver and LeafGreen and it seemed like they would never run out of increasingly made-up colors (until, of course, this new generation of games, Pokémon X and Y). My high school boyfriend bought me a Game Boy SP, one of the most thoughtful gifts I've ever received. It flipped open and shut and had a backlight, so I could stay up nights playing without having to deal with one of those horrible squiggly lights you plugged into your device's USB port. We broke up when we left for college but I still have the SP.

As I got older, Pokémon became less about the systematic wringing out of everything the game had to offer (collecting all the monsters, beating every possible trainer in battle) and more about the rhythm of playing. The games got easier, I think — although I also developed better motor and cognitive skills so who even knows — and as more and more Pokémon were introduced (there are over 700 [!] as of X/Y) I became more inclined to cruise through each new-but-familiar narrative without stopping to catch every one. I no longer dove fully into the Pokémon world and instead started to tuck it into my own, next to college applications and relationships and long car rides with my mom. Pokémon, for me, had become pocket-sized.

Finally, with Pokémon X/Y, it feels like the game has evolved too. The bad guys, for one, are a much more sinister group than the generically evil Team Rocket of the first generation and its later iterations. To be sure, they're just as goofy as Jessie, James, and the perpetually hunched Giovanni: The top Team Flare execs sport eyewear that looks like knockoff Google Glass, grunts make an arm motion when they attack that can only be described as vogueing, and Lysandre, the head baddie, is a dead-ringer for Carrot Top. But Lysandre is a sad and scary villain. His philosophy, that there aren't enough resources or space or happiness to sustain the ever-growing population of the world, comes frighteningly close to the suggestion of ethnic cleansing, and his plan to construct a machine to carry this out can't be thwarted by a mere Pokémon battle like in past games. The most chilling part of Lysandre's vision for a perfect world is that it doesn't include Pokémon. Upon confronting him at his secret lair, he tells you, in tears, that the creatures all have to go because people are bound to use them to fight battles and seek power. At that moment, late one night in my bed, I felt an unmistakable fear of loss.

That's what makes X/Y so great: It's sophisticated and self-aware enough to have raised the stakes without drastically altering the original framework that made it so appealing.

To that end, the new game provides way more options for customizing your player character. (Skin tones now come in three colors instead of just one and outfits can be purchased at stores throughout the new game.) My best friend, peering over my shoulder as I played on the subway one night, burst out laughing when she got a good look at my character.

"Alanna," she said. "That literally is you."

I shrugged, a little sheepish but secretly proud of her shoulder-length red hair and penchant for mustard-colored clothing. I'd spent thousands of Pokédollars and close to an (actual real-life) hour roller-skating through Lumiose City to find an outfit that I would have worn myself.

There's absolutely a place for games where you can separate completely from your character, can throw them into battle and into speeding cars without needing to identify or empathize, but Pokémon has always lived somewhere closer for me. Maybe it's because your character herself is more of a conduit than a real participant in the game's action: A Pokémon trainer's goal is to gather a team of six friends-servants-pets to work as an extension of themselves, and so it's not that hard to go a step further and transpose yourself with that little avatar. These are game-Alanna's creatures, her adventures, and therefore they are mine (especially if she is rocking that much mustard).

When I was 10, playing on that first Game Boy Color, I had a friend who always collected every single Pokémon without fail. I had another whose favorite thing was to link up with those awful inflexible connector cables and battle people he actually knew, rather than the in-game opponents. When I played through X I found that I wasn't interested in capturing any Pokémon beyond the ones I wanted for my party, besides the requisite legendaries, and instead focused on making my way quickly through the game, stopping to ferret around for secrets and tiny details scattered throughout the map. I liked entering people's houses and rooting through their trashcans. I liked talking to trainers after I'd beaten them and going completely out of my way in pursuit of items I never used. These little tokens, this seeking out of companionship and flashes of personality, aren't something I much cared about as a single-minded kid. I am softer now than I was then, becoming more interested in means than in ends. In this way, the Pokémon universe has expanded and contracted and yet always been the right size for me.

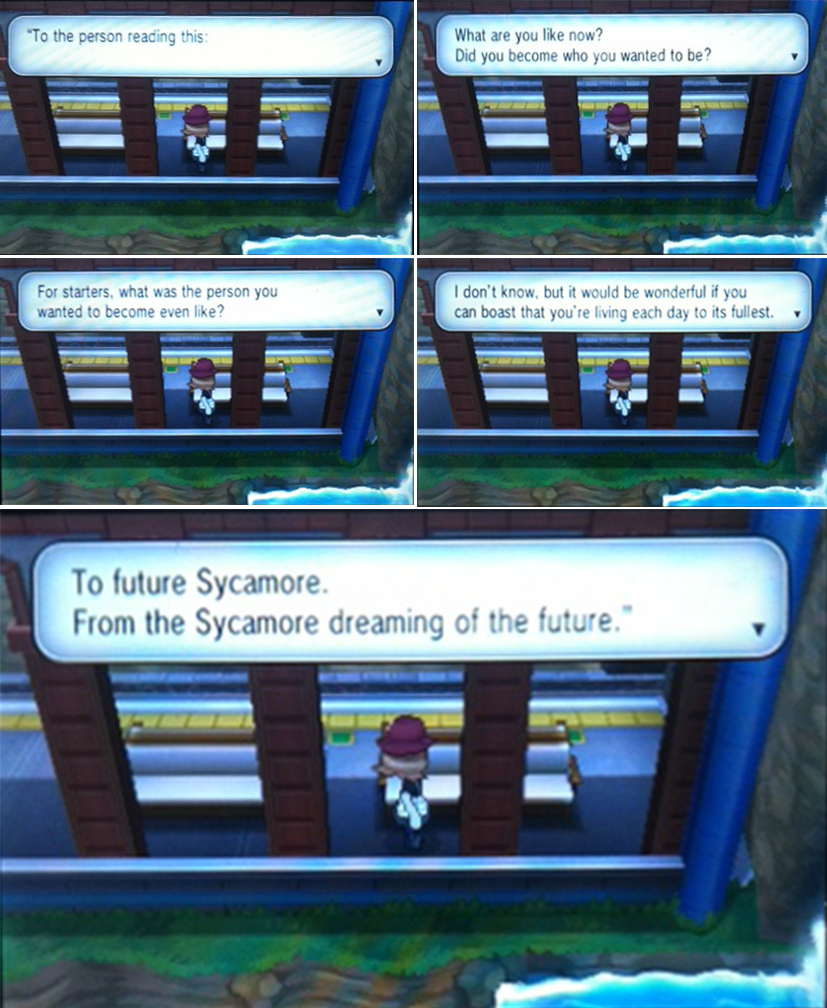

The most moving moment of Pokémon X was not when I beat the Elite Four or watched the final cut sequence after weeks of gameplay (having a job, it turns out, can be a major hindrance re: becoming a Pokémon master). It came after I'd battled Professor Sycamore, the main character's mentor and hottie extraordinaire, in a town called Couriway near the end of the game. I'd tried not to read too many spoilers before I started (although really, given Pokémon's cyclical nature, it wouldn't have ruined much) but I had seen that if you were willing to click around up by some of the town's benches, you'd find a letter that a younger Sycamore had left for himself long ago:

I did, and I cried. It felt like a message received from my 10-year-old self.