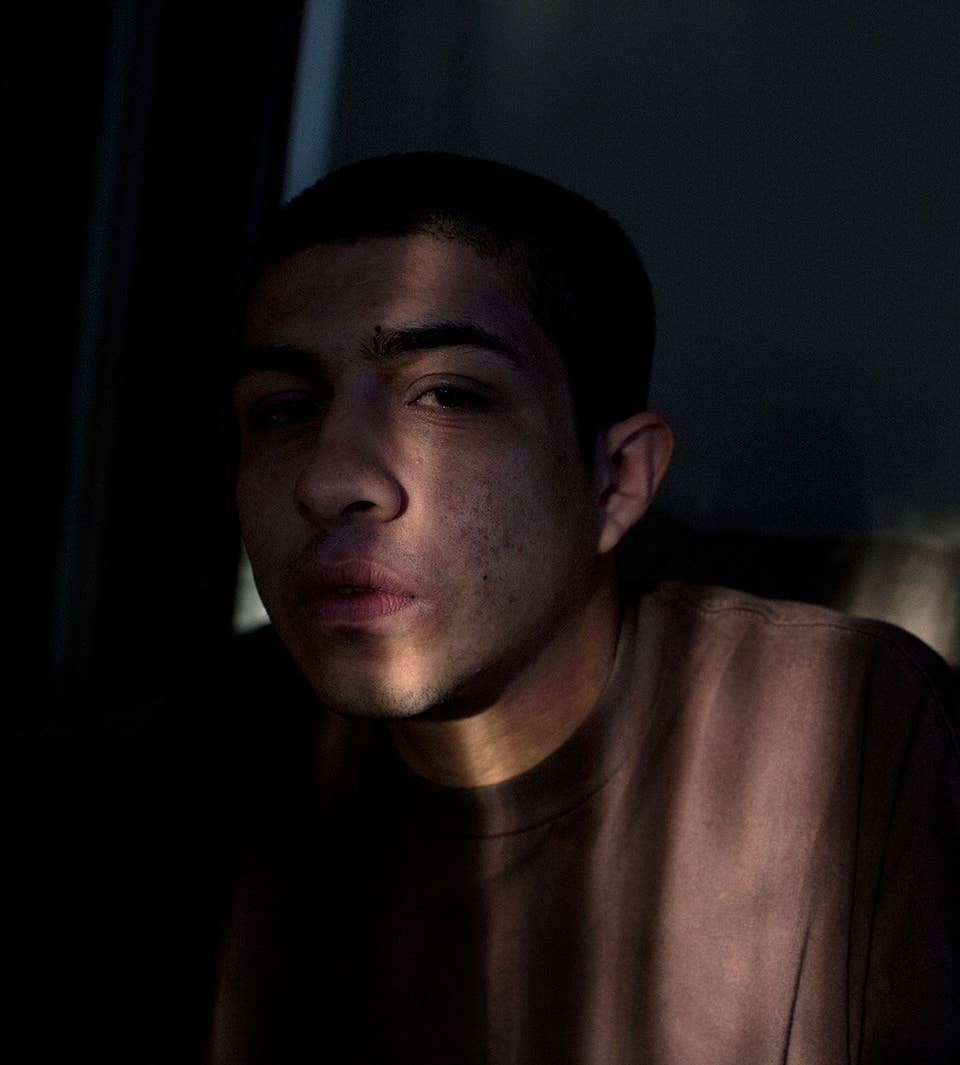

Unlike a lot of 22-year-olds, Peter Arellano used to spend a lot of time worrying about how to avoid being seen publicly with his father, or his friends.

There are hundreds of others just like him, facing arrest if they're seen with the wrong people in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Echo Park in Los Angeles.

Such is life under a gang injunction, a civil court order that can place sweeping everyday restrictions — such as not being able to carry a marker pen or drink in public — on alleged gang members within designated areas.

“It’s like you’re free, but you’re in a prison at the same time,” said Arellano, who's been given a brief respite from the injunction while a court rules on a motion in his case. “It limits who I can hang out with and, yeah, that includes the people I love.”

Proponents say the restrictions, pioneered in the 1980s when gang killings in Los Angeles were at a record high, reduce crime by hampering the movements of gang members on their own turf.

But civil rights groups have argued for years that the injunctions sweep up youth who aren’t actually in gangs, allowing authorities to impose parole-like conditions on them without first going through the criminal court process.

"The city uses gang injunctions to place restrictions on people that are similar to parole or probation, but without requiring prosecutors to first prove that a person has actually committed any crime,” said Peter Bibring, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Southern California who is litigating Arellano’s case. “Gang injunctions tend to go through without anybody really representing the gang, and in very few instances does anybody argue whether the injunction should be entered at all.”

But opponents have so far been unable to strike down the injunctions in court, even as the restrictions proliferate in cities across the US, especially in California.

“If you bring a lawsuit against something people first think of as a tool to stop gangs, you’re already at a disadvantage,” said Olu K. Orange, director of the University of Southern California’s Dornsife Trial Advocacy Program. “Public perception does affect cases like these to a large degree.”

Now groups like the the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have started attacking certain provisions of the injunctions, such as curfews, as being unconstitutional, an argument that tends to find more public sympathy.

“At some point, they might have been a good tool for law enforcement to help the community, but the cops just got these and went nuts.”

Orange has had success with the strategy. He won a lawsuit against Los Angeles in 2016 for imposing curfews in gang injunctions that had been declared unconstitutional by California courts.

The settlement resulted in a $30 million investment in job training and apprenticeships, as well as an expedited process for getting removed from a gang injunction.

At the time, Orange said the curfew imposed by 26 gang injunctions had turned LA “into a Jim Crow-era ‘Sundown Town,’ forcing several thousand black and brown residents indoors on a nightly basis.”

“As soon as the g-word [gang] is used, discrimination becomes OK,” Orange said. “Unfortunately, many aspects of gang injunctions, broken down piece by piece, are unconstitutional and have unfairly been brought to bear primarily on low-income communities of color.”

Arellano was subject to an injunction that was initially secured for six gangs, with individual people added later. But without a chance to fight it in court, attorneys argue their clients were robbed of their due process rights.

If the ACLU prevails and Los Angeles is forced to give people a court hearing before they’re added to a gang injunction, it would deal a major blow to the city because it doesn’t have the resources, Orange said.

“At some point, they might have been a good tool for law enforcement to help the community, but the cops just got these and went nuts,” he said.

Arellano grew up in Echo Park, before hair salons offering $10 cuts and tiny family-owned restaurants gave way to the craft roastery Blue Bottle Coffee and hip alcohol-serving arcades. In a corner of his bedroom, he has a glass cabinet filled with monster figurines that he carefully paints in his spare time — a hobby he picked up in high school.

Many people in his neighborhood are gang members, including his father, who is also subject to the injunction. For almost a year, he couldn’t be seen with his father, who has been behind bars since April 2016, when he was charged with attempted murder and assault with a firearm.

Arellano, who insists he's not in a gang, was accused of using a gun to intimidate someone who wanted to leave the Echo Park gang in 2013, but prosecutors ultimately didn't have enough evidence to bring a case.

The next year, in 2014, Arellano was charged with vandalism. Prosecutors weren’t able to pin a gang enhancement on him, but he pleaded no contest to vandalism and performed community service.

Then, in 2015, Arellano was served with the injunction when two people he was with were arrested, one for vandalism, the other for a weapons possession violation for carrying a box cutter.

Until November, when city officials agreed not to enforce the injunction while a court ruled on a motion in his case, Arellano missed neighborhood parties and concerts.

“It sucks, it feels like your life is limited,” Arellano said. “You can’t do what regular people do, you can’t drink with friends, go to the lake, be a part of the community.”

The LAPD and city attorney’s office declined to comment on pending litigation. But in federal court documents responding to the ACLU’s complaint, city attorneys said “due process does not require the city to provide a hearing before service of the judgement permanent injunction.”

In June 2013, then–LA City Attorney Carmen Trutanich also argued that the Echo Park injunction would curb gang-related graffiti, assaults, and homicides.

“This injunction will be an important tool in curbing the escalating criminal activity of these six rival gangs and bringing peace to our neighborhoods,” Trutanich told the court.

The restraining order complaint accused the six gangs of terrorizing residents, including “innocent young male Hispanics,” and threatening people with violence if they report crimes.

The Los Angeles city attorney’s office has a process for removing people from a gang injunction, but it can be long and arduous, said Josh Green, criminal justice program manager and staff attorney with the Urban Peace Institute.

Of the 9,400 Angelenos subject to gang injunctions — a majority of whom were not listed in the original version — less than 50 have managed to get themselves removed, Green said.

“In some cases, it took two years, and this included a client who had never been arrested for anything,” Green told BuzzFeed News. “The truth is, it was taking so long, it was very hard to get people to believe the process had any legitimacy.”

The freedoms people lose — the ability to spend time with family in public and First Amendment rights — are so important that any provisions on the back end will never be enough, he added.

“The fact that it’s so easy to get on the injunction and so difficult to get off an injunction demonstrates that we’re not really considering the consequences in the communities where these injunctions exist,” Green said. “What we’ve seen is the benefit to the community is really low, the burden on the individual is actually significant, and it’s very difficult for a person to find their way out from underneath the burden.”

Gang injunctions occupy an odd legal space in that they start out as a civil proceeding but turn into a criminal matter once provisions are violated, which could lead to fines, jail time, or even a conviction on someone’s record, said Ana Muñiz, an assistant professor of criminology at the University of California, Irvine.

“It's a Trojan horse,” Muñiz said. “It’s like being on probation or parole without being convicted of a crime.”

Ultimately, Muñiz argues, gang injunctions aren't about reducing crime rates, but about gentrifying communities. In Echo Park, the injunction was imposed in a historically Latino area at a time of declining crime rates as an influx of white residents moved in.

“That’s why they put in the Echo Park injunction,” Muñiz said. “They’re not actually a long-term crime reduction tool. That has never been what they’ve achieved.”

Research shows that some injunctions result in about a 10% reduction in certain crimes for six months to one year after they're implemented, Muñiz said.

In an article published in Social Problems, Muñiz argued that Los Angeles's first gang injunction in 1987 targeted the Playboy Gangster Crips because the neighborhood was undergoing a demographic shift.

“Despite the sanitization of race in gang injunction policy, fear of black men and stereotypes about black families were central to the rationale of the injunction,” Muñiz wrote. “The injunction was meticulously designed to control the movement of black youth by criminalizing activities and behavior that are unremarkable and legal in other jurisdictions.”

But for some residents in gang-afflicted neighborhoods, the injunctions have brought real change.

“As a resident, it made a huge difference on my corner, at least,” said Katherine Pinney, a resident of the Los Angeles community of Highland Park, which is covered by three gang injunctions. “Gangs are still a problem, but at least they’re not congregating.”

The combination of community-based policing, neighborhood watch, and businesses feeling brave enough to call the police also helped make a difference, she added.

“You still have graffiti, but the speed with which things get cleaned up is very fast,” Pinney said. “The injunction added some bite, so the community could actually do something to improve it.”

A study that looked at eight years’ worth of data from four law enforcement jurisdictions in Los Angeles County found that violent crime rates dropped between 5% and 10% per quarter during the first year of a gang injunction.

Yolanda Nogueira, past president of the chamber of commerce in Highland Park, remembers how the main thoroughfare, York Boulevard, was before the gang injunctions. Local gangs gathered on street corners and fleeced business owners by demanding a fee for “protection.”

But all that has changed, bringing with it an influx of investment. Small businesses offering custom-made donuts, horchata lattes, and craft beers have replaced former pool halls, Mexican bakeries, and aging bars.

“They helped slightly because [gang members] were afraid to congregate,” Nogueira said of the injunctions. “You didn’t see them in bars, corners, or walking down the street, but they were still there. It’s been cleared up, and a lot of them moved because of gentrification because they were renters.”

Arellano, who protested the injunctions before they were approved, saw the writing on the wall when Echo Park started to gentrify, fueled by a multimillion-dollar revamp of the famed lake.

“I had a sense that the cops were going to harass us,” Arellano said. “I knew where this was going.”

With a baby on the way, Arellano said he hopes it’s not a boy.

“I hope it’s a girl,” he said. “That way, the cops won't harass her like they did me.” ●