“Put it in the dictionary next to emotionally broken psycho.”

Hillary Benton was talking about Lorde when she wrote that sentence, a third of the way through Benton’s 29-slide PowerPoint exploration of whether or not the pop star is “boning” her creative collaborator Jack Antonoff. But anyone who’s gone on a journey like Benton’s — a mad, obsessive attempt to understand something about the love lives of total strangers — would probably acknowledge that there’s at least a little projection going on here. Is Lorde an emotionally broken psycho? All I’m saying is: Takes one to know one.

In fandom, getting involved with the idea that two people — IRL figures or fictional characters — would be hot together is called “shipping.” But you don’t have to know the word to have participated in the phenomenon: If you’ve ever rooted for a couple to get together on a television show, you’ve shipped them; if you’ve ever spent an hour or four trawling through an ex’s Instagram likes, trying to figure out who they’re dating now, the difference between you and Benton is mostly that she got a viral PowerPoint out of her trip down the rabbit hole.

The social curiosity that drives us to speculate about other people’s love lives is pervasive, and common. But in the last few decades, it has combined with the access and connectivity the internet allows, as well as our fraught relationship to celebrity — how close these stars seem to us, and yet how vastly far away — and spurred ever more elaborate imaginings. Benton’s PowerPoint was quite something, but it’s not nearly as intense as some of the intricate conspiracy theories currently populating the internet, which claim that nefarious forces are deliberately preventing us from knowing the truth of who our favorite celebrities are banging (or, more often, falling helplessly in love with).

Most of these theories hold that a star has found a same-sex soulmate and is being either pressured to stay quiet about it or outright closeted by their “team.” Conspirators believe that star-crossed love has blossomed between Larry Stylinson (One Direction alumni Louis Tomlinson and Harry Styles) and Kaylor (Taylor Swift and Karlie Kloss), as well as Riverdale heartthrobs KJ Apa and Cole Sprouse, barely-out-of-their-tweens Stranger Things actors Finn Wolfhard and Jack Grazer, and even bona fide movie stars like Carol’s Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara.

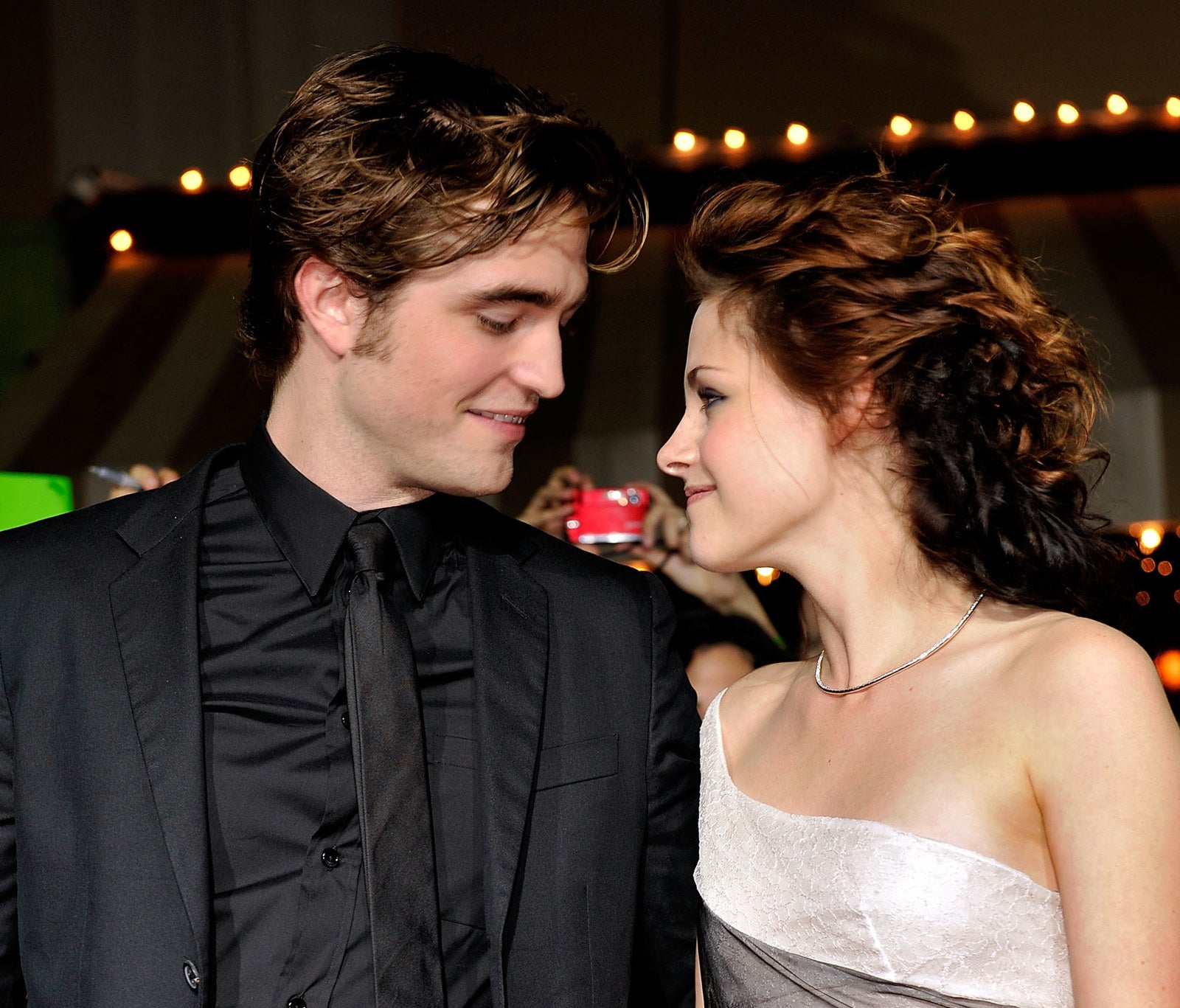

But there are also conspiracy theories about heterosexual couples, which speculate that long-separated pairs like Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart are hiding not just their continued romance but three children from us. (Canadian ice dancers Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir are rumored to have only one secret baby. So chaste!) Now even a brand-new, still-on couple can get the conspiracy treatment: Refinery29’s Kathryn Lindsay, who calls herself a “Pete Davidson & Ariana Grande Truther,” recently wrote about her theory that the couple have been dating for longer than their public timeline admits. “It's something I'm going to continue to think about every day until I'm given answers,” Lindsay says, tongue only partly in cheek.

These theories reveal not only how obsessed we are with celebrities, but also how desperately we want them to be obsessed with us in return. It’s one thing to suggest that a celebrity may not be telling us everything; most of us can agree that that’s the case, and we mostly acknowledge that that’s because they don’t know us, and they like to keep their personal lives, you know, personal.

In contrast, believing that the celebrity is not just withholding information but involved in an active conspiracy to keep us from the truth places us at the center of their lives: either because they’re trying to fool us, or because, as these theories suggest, they’re trying to fool most people, but they also want a select few of their most observant fans — those who are ready, those who get it — to know their true selves.

And so, the theory goes, these stars have spent hours and days crafting elaborately coded messages that can be disseminated by social media and paparazzi photographs. These clues will catch the eye of the knowing without alerting the masses. If you can see and understand them, then it must mean that your relationship with your fave isn’t transactional or one-sided, but instead communicative, and personal. It must mean, on some level, that they could — that they want to — love you just as ardently and intimately as you love them.

Writing for the Guardian, Daniel and Jason Freeman recently posited that we’re living in a “golden age of the conspiracy theory”: a moment when, all across our culture, we find mounting accusations of deep state manipulations, false-flag actors, and fake news. “In place of anxiety and uncertainty, we are soothed by what feels like knowledge,” they write. One of the most seductive things about a conspiracy theory is how neatly it explains the world: not as a collection of random and inexplicable forces, but as a coherent narrative controlled by a single, powerful hand.

And the only thing more powerful than that hand is our ability to see it at work, and call it out for what it is. “Our bruised self-esteem is boosted by the sense that we are one of the small minority who really know what’s going on,” the Freemans write. “And thanks to the Internet we’re able to connect with these like-minded souls: suddenly we can feel part of a community.”

That community is what gives people a way to instantly suss out whether anyone else, say, looked at a photograph of two models leaving a nightclub holding hands and had the same that’s not just a friendly touch reaction to the image. So it’s not surprising that celebrity conspiracy theories began to blossom at the same time the internet did, in the early 2000s, as fan communities explored popslash, bandom, and the question of what, exactly, went down between the Lord of the Rings cast members during their time filming in New Zealand. (“Tinhat,” a term often used by nonbelievers to identify conspiracy theorists, was coined to describe the level of crazy that most of fandom assigned to those convinced that Elijah Wood and Dominic Monaghan were dating.)

In the world of celebrity conspiracy theory, a cigar is never just a cigar.

The other key ingredient of the conspiracy cocktail that the internet provides is vast amounts of information. Where celebrity gossip used to be disseminated through weekly tabloids, now we have 24/7, 360-degree access, some of which is genuinely unmediated, and some of which only feels that way. Many celebrities livestream on social media, and those who don’t are often still under constant surveillance by professional paparazzi and their amateur imitators, a populace empowered and connected by smartphones.

Now we can try to match up a bunch of facts — he was here at this time on this day, he was wearing this shirt, his sister liked this post on Instagram — with the official narratives, and see for ourselves how far apart they are. Instead of just suspecting that we’re not hearing the whole truth, we have some evidence of what, exactly, we’re missing out on, as well as some ideas about what else could be going on.

The key word here is “evidence.” For most of us, a fact is just a fact: Sprouse recently tweeted something about Waluigi, which to most people looks like a response to the video game character’s recent humiliation at the hands of Nintendo executives. But once you’re enmeshed in a conspiracy theory, that tweet becomes a coded lament about how Sprouse was forced to miss his secret boyfriend’s birthday party by their evil CW overlords.

This ability to subsume anything and everything into an imagined narrative — to transform the world from a place of neutral facts to charged clues — is a hallmark of conspiracy theory thinking. In a 2013 post, one blogger tried to claim that pictures of Zayn Malik asleep in the bed of someone other than his then-girlfriend, Perrie Edwards, had been taken from his bandmate and “actual” boyfriend Liam Payne’s phone, and that Malik was letting us know onstage at One Direction concerts.

Analyzing a video of a rendition of the band’s song “Live While We’re Young,” which includes the lyric, “And if we get together / Don’t let the pictures leave your phone," Tumblr user lsmoments writes: “Watch closely, because Zayn does something interesting here — he takes his microphone and switches hands. By doing that, he indicates that it’s not just casual pointing. It’s deliberate. Why does he do that? ... My guess is that he’s trying to make it as obvious as possible that he’s pointing to Liam, and not Niall. If he pointed with his right hand, the angle would make it more ambiguous who he was pointing to. But since he points with his left hand, you can see him pointing to the phone that Liam is holding, and also to Liam. ... I believe this is Zayn’s way of saying that yes, it is indeed Liam’s phone that got stolen, and it’s Liam’s phone that the pictures were taken from.”

In the world of celebrity conspiracy theory, a gesture is never just a gesture; it’s a symbol, waiting for us to decode it and understand it. A cigar is never just a cigar.

So what do conspiracy theorists do with all the information that seems to flatly contradict their theories? They find a way to subsume that, too. The idea that everyone involved is playing a game of three-dimensional chess at all times can be grounds to reinterpret or dismiss even the most contradictory signals as needed, to make sure the theory keeps working. The denial, in fact, is crucial: That’s how you know there’s a conspiracy afoot. If someone has to deny a story, the logic goes, ask yourself: How did the story get out there in the first place? Every denial is just an opportunity to remind yourself that that’s what they want you to think, man.

Even the lack of a denial can be taken as evidence to strengthen the conspiracy theory. “How come nobody has asked them about the silly rumor going around the internet that they have a secret baby?” blogger Dubemoir writes of Virtue and Moir. (Never mind that the pair have consistently denied being a romantic couple, which you would think would obviate the need to clarify that they also don’t have a baby together.) Dubemoir sees this as proof in itself that the media is complicit in hiding the truth: that they don’t ask because they don’t want to make the skaters lie about something so intimate and vulnerable. “They love to deny shit. Why not this?” she wonders.

This is one of the crucial differences between garden-variety speculative celebrity gossip and hardcore conspiracy theories: the degree to which they resist or outright contradict a celebrity’s self-stated identity. There’s a difference, for instance, between people speculating about Kristen Stewart’s sexuality before she officially declared herself “so gay, dude” on SNL, and insisting on Louis Tomlinson’s secret romance with Styles. Stewart hadn’t yet made a big, clear, public announcement about her sexual orientation (though there’s an argument to be made that for years beforehand, she was never really hiding). Tomlinson, however, has emphatically and repeatedly insisted that he is straight.

But Larries refuse to take those denials at face value. They have an answer for everything: In the case of his tweets, they’re pretty sure that @Louis_Tomlinson wasn’t being written by Louis Tomlinson. Meanwhile, Robsten conspiracy theorists insist that Stewart’s coming-out was a satire, intended to poke fun at anyone stupid enough to believe she was serious.

@JennSelby The fact that you work for such a 'credible' paper and you would talk such rubbish is laughable. I am in fact straight.

Conspiracy theories are constructed to be un-debunkable. No denial is ever real. No denial is ever enough. Anything that appears to contradict the theory is merely part of the conspiracy to repress it. Anything that doesn’t make sense is evidence that the people running the conspiracy are somehow simultaneously incompetent and all-powerful.

An anonymous question was recently submitted to Cassandraatthegates, a Larry blogger, asking her what she would do if Tomlinson never came out — if, in fact, he continues to date women and even have children with them. Would she still support Tomlinson in his career?

Cassandraathegates responds, “The idea that Louis may not be free of Sony or his stunts for years actually isn’t new to me ... I think Sony have been playing a long game and will continue to do that.” In other words: a true believer doesn't necessarily expect an ultimate confirmation to prove the theory. The mission is simply to keep believing; to know, in your heart, that you're right.

Conspiracy theories might seem silly, easy to dismiss as the work of hardcore obsessives who have taken their high school education in close reading a few steps too far. But it’s not all heavily coded song lyrics and claims that a pair of rainbow teddy bears dressed in bondage gear are sending you secret messages. Conspiracy theories are fascinating because they allow us to see the sand in the gears of our culture: They speak to genuine frictions and frustrations, even if the way they do it is deeply flawed. In particular, they raise interesting, difficult questions about how we can appropriately discuss others’ sexuality, especially as we try to move toward an increasing acceptance of ambiguity and fluidity in sexual desire and identity.

Celebrities are trained to be equal parts friendly and evasive. They do withhold information from us, particularly about their love lives; when they choose to make the personal public, it can be a calculated move meant to reinforce or adjust their image. And on top of that, the media does have a tendency to assume straightness as a default, and then to straightwash queer couples by terming them “close friends.” There are instances when calling someone a gal pal is not a polite refusal to speculate, but instead a willful misreading: There’s a reason the phrase has become a meme.

Conspiracy theories speak to genuine frictions and frustrations, even if the way they do it is deeply flawed.

Conspiracy theories give us a way to deal with both of those larger cultural realities. Because we’ve been taught to equate skepticism with sophistication, especially where the media is concerned, entertaining a conspiracy theory can let someone feel both appropriately discerning, and also particularly generous. It allows us to air our media literacy — that’s a staged pap walk, they had to know photographers would be there; that’s a publicity fauxmance, they both have movies coming out soon — as well as our ally bona fides, when we look at a pair of men or woman hanging out together and announce supportively, “I can totally see that being a thing!”

Sometimes it totally is a thing (see the so-called gal pals above). Even if it isn’t, there’s nothing wrong with seeing something potentially romantic or sexual between two women or two men. In fact, just as it’s important to allow for queer readings of texts, it’s equally critical to normalize the queer gaze on interpersonal relationships.

But it’s also true that people are not texts, and so, while we can make an argument for the validity of our readings, we can’t necessarily claim them as the truth. Talking honestly about what a person’s behavior suggests is not the same thing as claiming to be sure of what it means — much less asserting that anyone who disagrees with you is categorically anti-gay.

When Jack Antonoff denied dating Lorde, he called the speculation around their relationship “hetero normative gossip,” implying that culturally, we’re incapable of seeing man + woman and not automatically assuming sex!!!! So you can see, sort of, why Tumblr user its-gonna-be-okay-love signs their analysis of photos of KJ Apa and Cole Sprouse together with “Heteronormativity’s Nightmare.” In their mind, what they are doing is looking at a photo of two men touching each other and erasing that “straight until proven queer” default: Their argument is, if you look at this and don’t see anything gay about it, that’s because you refuse to see gayness, not because there’s nothing to see.

They think they’re terrorizing nonbelievers by pointing out that not supporting and believing in Coleneti (Apa and Sprouse’s ship name) is only possible if you are willing to live a blinkered, heteronormative life. They discount out of hand that a reasonable person might look at the evidence — which yes, involves a lot of physical affection between two men, but also Sprouse kissing rumored girlfriend Lili Reinhardt on the street in Paris — and read it differently. They claim that there’s only one way to read it, and that way is theirs.

To believe otherwise, in their minds, is to be naive about the media (Reinhardt is, after all, also Sprouse’s costar — maybe it’s all a publicity stunt?), but also to ignore the work that they believe these stars are doing to communicate their truth to us. They are, after all, being closeted against their will, so when they touch each other or even acknowledge one another on social media, they’re doing it at some risk, and with the hope that we’ll see it, and know exactly what they mean by it. Conspiracy theorists would argue that celebrities actually can be read like texts, because that’s how they intend us to interact with the avatars they present to us, the personas we get in place of their actual personalities.

The most committed conspiracy theorists are careful to say that they aren’t shipping, or participating in a fantasy, which involves some amount of projection. No, they’re completely objective viewers who deal strictly in facts. “There is no talk anywhere of shipper fantasies,” writes one anonymous commenter on Dubemoir’s blog. “No one here is sighing and hoping and wishing. It's stated as fact. The blogger and a few others have said they know this from personal sources. Others, like myself, have connected the dots from the public sources available and come to certain conclusions. Not because we project any fantasies onto VM.”

If conspiracy theorists believe that they aren’t in it for the fantasy, what are they looking for? What is it that keeps them assiduously tracking every move a celebrity, and their family and friends and team, and their families and friends, make?

Sometimes the answer is representation: There is still a relative paucity of stories about queer life and love, and the search for identity and self-acceptance is always easier to navigate when you have a role model. Bloggers talk a lot about offering support, both to the supposedly queer-but-closeted stars themselves and to the fans who see themselves reflected in their lives. For straight believers, running a so-called support blog can feel like an important act of allyship: a way of aligning themselves with (or perhaps inserting themselves into) the cause.

Some of the initiatives that have come out of these conversations are projects like Rainbow Direction, which was created to encourage folks to make a safe, welcoming space for LGBT fans at One Direction concerts (and now at ex-members’ solo outings). Rainbow Direction is particularly effective because it doesn’t rely on the narrative that any of the boys have to be queer in order for their concerts to be a powerful experience of acceptance for queer fans.

The more time a person spends being convinced and trying to convince others of a particular Truth, the less likely they are to be willing to give it up.

Building up a version of a person you don’t know as a role model or hero is both completely understandable and very precarious. This is especially true when you’re tying them to an intimate part of your identity, like sexual orientation. It can be hopeful to believe that a celebrity — a seemingly mythic, larger-than-life creature — can understand your most vulnerable self. But that willingness to be tender can also cause deep, lasting wounds if the celebrity doesn’t comply with your version of the story. And conspiracy theorists are very, very attached to their version of the story.

Remember how stridently Larry believers argue that @Louis_Tomlinson isn’t being written by Louis Tomlinson? That’s in part because his tweets denying Larry have bordered on being anti-gay. And if Louis isn’t gay, and closeted — if he wrote those words in those tweets, and meant them — then this person who they’ve sunk hours and years and incredible amounts of love and devotion into thinking and talking about, well, he might not have been worth it at all.

Plus, being wrong is just embarrassing. The more time a person spends being convinced and trying to convince others of a particular Truth, the less likely they are to be willing to give it up. So conspiracy theorists create increasingly minutely detailed timelines and surround them with ever-more baroque theories, as when One Direction announced it was going on hiatus and everything that didn’t fit the Larry narrative was declared a casualty of an all-out PR war between the band’s old team (which was anti-gay and intent on tanking the 1D brand if they couldn’t own it) and their new team, an enlightened group which would finally allow The Coming Out to come. When it didn’t, Larry believers rationalized that in order for Harry to be allowed to sign with Columbia Records, Louis had had to agree to stay at Sony, and in the closet.

A belief in these types of unbreakable contracts that supposedly govern stars’ behavior serves to exculpate the celebrity from any lying or obfuscation — or shirking the burden of representation — by making it involuntary: She doesn’t want to lie to me. She actually has to. It also further shifts the burden of blame and allows believers to paint those in close contact with the celebrity as the source of this bad behavior. Anyone who might compete with us for intimate contact with them is thus discredited and sidelined from our understanding of their lives.

Here’s Dubemoir writing, in a 2,500-word blog post from 2013 titled “I feel bad for Toddler Moir,” (that’s Moir and Virtue’s secret child) about why she believes that the ice dancers’ team (“Moirville”) are not just encouraging them to hide their theoretical secret relationship, but actively trolling fans who believe in it by sharing photos of Moir with his girlfriend at the time, Cassandra Hilborn. “It's more than pretending Scott/Tessa's marriage is a secret and insisting on the sham against all evidence,” she writes. “As the sham has morphed over time, I think it's now morphed into an alienation device. The more we're alienated, the more Scott and Tessa belong to Moirville.”

We talk a lot about the ways in which celebrities act as role models, both political and personal. But what we talk about less is how our behavior, our individual nuanced desires and actions, becomes part of the undifferentiated mass of “the public,” which, in turn, shapes their behavior. Because we do have a reciprocal relationship with celebrities — but it’s often not the kind that we, or they, actually want.

Last summer, a journalist for the Sun interviewed Louis Tomlinson and got the most candid response from him yet about his feelings on the Larry Stylinson conspiracy theory. “Louis said the fear that fans would overanalyze every minor interaction between the two stars caused them to stay away from one another,” Dan Wootton wrote.

“It created this atmosphere between the two of us where everyone was looking into everything we did,” Tomlinson told Wootton. “It took away the vibe you get off anyone. It made everything, I think on both fences, a little bit more unapproachable.”

(Again, Larries discount this interview out of hand: The 2016 news that Tomlinson was going to be a father was broken by a Sun editor named Pete Samson, who’s married to the global head of media at Syco, One Direction’s former record label, which means that the Sun is in Simon Cowell’s pocket and nothing it prints about the boys is true.)

In a way, conspiracy theories do allow believers to get what they want: When theorists are numerous and vocal enough, they influence a celebrity’s life. They get his attention. They change his behavior. But that change might involve him becoming more private and guarded, more painfully aware that any comment or garment or Instagram like can be taken out of context and made to fit into someone else’s theory of how his life makes sense.

These theories also end up affecting celebrities’ civilian loved ones; when Tomlinson’s son was a baby, Larries suggested that he was a doll, and now that he’s older they suppose that he’s someone else’s child being used to play the role. It’s one thing to wonder about a famous twentysomething millionaire; it’s quite another to cast aspersions on his toddler son. People also tweeted screencaps from a porno they believed starred the child’s mother at Tomlinson’s 15-year-old sister, in an attempt to get her to admit that the relationship and the baby were fakes. Conspiracy theorists often say deeply misogynistic things about the women their male faves are publicly linked to; even commenting on the wrong Instagram can net you death threats.

In a way, conspiracy theories do allow believers to get what they want: When theorists are numerous and vocal enough, they influence a celebrity’s life.

But as weird or disruptive as conspiracy theories can be for the celebrities they center on, and the people around them, they can be even worse for the people who believe in them. For all the ways in which they open the door for a queer gaze on popular culture, they also shut out the parts of queer reality that don’t fit their narrative; they obsess over — and in the process valorize — a queer experience defined by closets and repression. Believers support one another, which is lovely, but then they “support” people who haven’t asked for their help or their labels. And they go after people who disagree with them with the vitriolic fury of the righteously self-certain.

One of the best things about modern understandings of sexual identity is the way that it allows for ambiguity and fluidity: It encourages us to think, for instance, Hey, maybe she’s dated men in the past, but now she’s dating a woman, and also, Does that mean...I could date a woman if I wanted to? What’s disappointing about conspiracy theories is how they take those conversations about how little we really know about celebrities’ personal lives and use them to promote a singular narrative which allows for no ambiguity whatsoever.

The true danger of the conspiracy theory lies less in the particulars of what any single theory espouses, and more in the type of thinking that they teach: suspicious to the point of being paranoid, deeply overdetermined, and committed to never taking no for an answer. Conspiracy theories are a simultaneous claim of deep intimacy with every detail of the facts, and also of grand mastery over them. They insist that only you (and those who believe and understand you) can see the grand, overarching plan that runs the universe. Which takes for granted that there is a grand plan, rather than merely a chaotic, arbitrary, and sometimes disappointing world, in which we do not know things much more often than we do. But if instead of knowing we can simply keep guessing, and wondering, and hoping, we’ll leave more room for everyone to find answers on their own. ●

Zan Romanoff is a full-time freelance writer and the author of A Song to Take the World Apart and Grace and the Fever. She lives and works in Los Angeles.