The federal agency in charge of processing citizenship has shuttered all of its offices at US Army basic training locations, putting up another roadblock for immigrant recruits who were promised a fast track to citizenship in return for their service.

It's the strongest indication to date that the Trump administration may be planning to shelve the popular program permanently, although Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has said he thinks it can be saved.

The US Citizenship and Immigration Services offices at Fort Benning, Georgia, Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, were all closed on Jan. 26, a spokeswoman confirmed to BuzzFeed News. Previously, those offices, which report to the Department of Homeland Security, had handled the naturalization of service members and their families.

Closing the offices means the end of expedited citizenship for recruits immediately after they complete basic training, the key element of the popular Military Accessions Vital to National Interest program, or MAVNI, which has naturalized more than 10,400 military service members since 2009.

“USCIS has decided to end the Naturalization at Basic Training Initiative,” says a USCIS public affairs guidance document dated from Jan. 30. The document cited “changes in Department of Defense requirements for certifying honorable service for US service members applying for naturalization.”

Those changes, announced last October, require active duty recruits to serve for at least 180 consecutive days and complete extra background and security checks before they can be granted citizenship. That delay forces many of the immigrant recruits to violate the visas that allowed them into the United States in the first place, subjecting them to immigration detention. It also denied them privileges that require citizenship, like applying for a drivers license in some states or seeking US residency for their to spouses and children.

The change in the program, which the Pentagon has laid to potential security threats and insufficient vetting, has angered recruits who say it violates the deal they made — providing the US military with much-needed language and medical skills in return for becoming US citizens after basic combat training, or BCT.

The enhanced background checks that cause long delays for recruits and endanger their immigration status began under the Obama administration, but they were still able to be naturalized after basic training. The time-intensive extra vetting created a backlog and put a strain on resources, causing the Pentagon to suspend the program in 2016, although Mattis has said his department is taking steps to resurrect it.

When 24-year old Nataliia Nezhynska completed her training at Fort Sill in 2015, she was told that only two out of 11 in her group were becoming citizens. After four months of additional training to be a combat medic, the Ukraine native was told “hopefully” they would be naturalized once they were deployed.

“You should be grateful you were even offered citizenship,” the immigration officer on base told the group of young soldiers, Nezhynska told BuzzFeed News.

“A few of us sat down right there,” she said in an interview from Vilseck, Germany, where she is serving in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. “We said 'we’re not moving until you tell us the date and time.' The decision not to leave without an answer was one of the best decisions of my life.”

The next day, she and four other immigrant recruits became US citizens and soon shipped out.

But with the major changes made to the program last fall, and now the closure of on-base immigration offices, stories like Nezhynska’s story are becoming rare. Soldiers at Fort Jackson, for example, are now two hours from the closest USCIS office in Charleston, and even so are typically not allowed to leave the base.

“USCIS and DOD will continue to work together to ensure that eligible service members have the opportunity to naturalize no matter where they serve,” the USCIS public affairs document says.

Without the usual promise of gaining citizenship after basic training, however, these recruits “are unauthorized immigrants as soon as they enter the gates,” said Margaret Stock, a retired Army officer and an immigration attorney who designed the recruitment program. “And there’s no prospective date when they can expect to become legal again.”

For example, many recruits are on F-1 foreign student visas, which they violate as soon as they report to basic training and can’t attend college anymore.

When they graduate basic training but don’t gain their citizenship, they are unable to work legally in the US or leave the country. Many are at risk of deportation. They also can't file visa petitions to legalize their spouses and children until they are US citizens. In some cases, they can't even deploy with their units.

“USCIS and the Pentagon ending expedited naturalization at BCT locations is very, very disappointing because the Army used this incentive as a recruiting tool and are now backing off their promise,” said Harminder Saini, a 24-year-old US Army recruit who immigrated from India and was recruited for his fluency in Punjabi.

“The fact that I potentially would be an American soldier but still not be an American citizen after finishing training doesn't feel right at all, and the thought of that is very heartbreaking,” he said. “American soldiers can potentially be killed in action and not be American citizens, which is the exact reason expedited naturalizations in BCT were installed in the first place.”

Thousands of recruits who are green card holders with a two-year conditional permanent resident status face the same issue, as that status could expire while they are still waiting to report to BCT and be naturalized. Others have had their contracts cancelled or postponed when US Army recruiters, though often well intentioned, make mistakes on the complicated paperwork and land them in risky immigration situations.

The immigration office closures are “yet another roadblock from USCIS and the Army to us becoming legal,” William Medeiros, a 25-year-old US Army recruit, told BuzzFeed News.

“Even though you swore an oath to defend the only country you know…I guess military service from immigrants is not valued as it once was in this country,” he said.

Born in Brazil and brought to the US as a child, Medeiros runs one of the Facebook groups for immigrant recruits where enlistees, deployed soldiers who have been through the program, recruiters and attorneys try to sift through the tangle of fluctuating Pentagon rules, added background checks and immigration paperwork.

“Damn how do you make excuses like that? 'Oh yeah I'm a soldier but I'm not a citizen'," read a recent post, echoing the sentiment at the news that they would no longer be naturalized after basic training.

The USCIS closures at basic training locations, and the guidance document, are “a public admission that there’s no more basic training naturalization, and no more expedited military naturalization,” Stock said.

The only way to get things moving has been to sue the government. In reponses, the government has argued for dismissal, saying that the plaintiffs would be naturalized after basic training. The closing of USCIS offices on base seems to make that difficult, at best.

Under the new policy, active duty recruits have to complete all necessary security and background checks, complete basic training, and serve for at least 180 consecutive days among other requirements. They also have to file what's known as a form N-426 to confirm their military service.

It used to take a day after basic training to complete that form. Now it requires a lengthy process, obtaining multiple sign-offs up the chain of command.

“When I did it, we said we’re doing everything we were told to do, and you’re not fulfilling your part of the contract,” Nezhynska said. “But we were lucky, now it’s much harder. People are losing their immigration status and becoming illegal, spending all their savings, it’s really terrible.”

Advocates worry that eliminating BCT naturalizations under the new policy will create more needless tragedies, citing the death of US Army Spc. Kendell Frederick. A native of Trinidad who moved to the US in 1999, Frederick was killed in Iraq in 2005 when his convoy was struck by a roadside bomb. The only reason he was in the convoy was to travel to another base to submit a duplicate set of fingerprints for his US citizenship application.

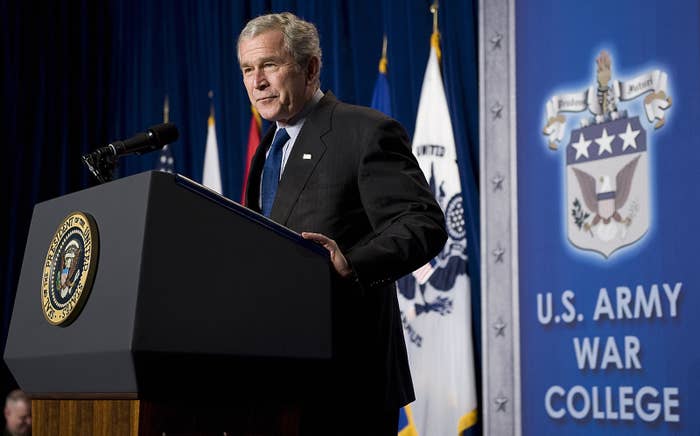

Three years later, President George W. Bush signed the Kendell Frederick Citizenship Assistance Act into law, which was meant to simplify naturalizations for members of the military. It was meant to eliminate the endless paperwork and stress on deployed service members like Frederick, whose citizenship application for the country he was fighting for kept hitting bureaucratic snags.

Advocates of the MAVNI program worry that the elimination of naturalization after basic training could mean reverting to an expensive, logistical nightmare of chasing service members around war zones to process their citizenship applications.

For the lucky few who do get processed, gaining their citizenship is not the solemn occasion it used to be, when they swore the pledge of allegiance at their basic training graduation, in uniform.

Some have been at a local USCIS office to check on their paperwork, wearing jeans and a t-shirt, and suddenly been told to come in, raise their right hand, swear allegiance and be done, without their families or anything special to mark the occasion, they told BuzzFeed News.

In court filings, the Pentagon has cited security concerns about sufficiently vetting of enlisted recruits. Attorneys representing immigrant soldiers say that the military has not presented evidence of a legitimate security threat. Now they fear naturalized recruits will be treated as second-class citizens for their entire careers.

Several soldiers who became US citizens through MAVNI have filed class-action lawsuits alleging that the Pentagon is discriminating against naturalized service members and blocking them from advancing their careers through the new security clearance requirements.

Despite the demoralizing news, the online community of MAVNI recruits has remained active, eagerly sharing any updates that look hopeful. Though they see the end of basic training naturalizations as a betrayal, just getting there after long delays is a victory.

“My platoon soldiers were shocked that I waited two years to join them,” one recruit asked. “How can they break their promise on BCT naturalization so easily like this? It is unbelievable.”

“Because you’re an immigrant,” another user posted. “Welcome to the fight, bro.”