One of the most dramatic changes in the American food production system is now underway in the egg industry.

A wave of big restaurants and grocers have committed to switch entirely to cage-free eggs, setting up the industry for a broad transformation. The problem, critics say, is that while the industry is preparing to flood the market with cage-free product, what consumers still overwhelmingly choose to buy are the cheaper, battery-farmed options.

Since the mid–20th century, when farmers started bringing hens indoors, the system has become so efficient that people can now buy eggs for less than 10 cents each, and the average Americans now eats an estimated 267 eggs per year.

But that efficiency came at a price: Life is miserable for hens in battery cages, and opposition to the system became a core concern of the animal rights movement, which has succeeded in turning dislike of the battery egg system into a mainstream issue.

Businesses have felt the pressure and responded. So far, about 100 grocery chains, 60 restaurant chains, and dozens of other major food businesses have promised to switch to cage-free in the next decade, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Together, they represent an estimated 70% of US egg demand.

That change will require egg farms to make big investments in new facilities and equipment to support hundreds of millions of cage-free hens. In certain cases, the farms will need to take on a lot of debt. Yet some egg producers worry that after they make huge investments to meet the new standards, consumers might end up being reluctant to buy a more expensive product just to feel a little better about themselves.

"All companies that have made public, cage-free pledges seem to be making their decisions based on brand perception, rather than current demand or scientific findings."

Only about 10% of eggs sold today are cage-free, and while pressure campaigns have succeeded in convincing businesses and the public that the battery farming system needs to change, people are not yet willing to vote with their wallets.

"The ability for the industry to do this conversion is truly subject to the demand for cage-free eggs from the consumer," said Jeff Coit, a poultry industry specialist at Farm Credit Services of America. "Today, we're not there. The vast majority of consumers are still buying the cheaper eggs on the shelf."

The cost of building a cage-free system averages out to about $40 per bird, which for a 1-million-hen operation — a common size in the business — gets expensive fast. About 86% of the country's eggs are produced by just 63 companies that have at least 1 million hens each.

In total, the industry estimates it could cost at least $6 billion to build enough cage-free housing to satisfy commitments made by retailers, restaurants, and food service providers over the next decade.

Coit said capital requirements vary, but some egg producers may need to come up with 40% or more of the cost, with the remaining funds subject to available debt financing.

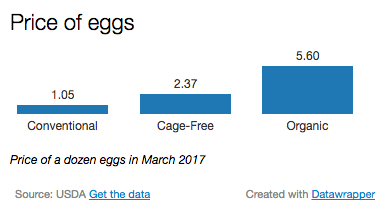

While shoppers already have the option to buy cage-free, "90% of consumers stand in front of the egg case, and they pick conventional caged eggs because they're economical," said Chad Gregory, CEO of United Egg Producers, the egg industry's lobbying group, to BuzzFeed News. A dozen conventional eggs in March cost an average of $1.05, or about 9 cents per egg. That's less than half as much as a dozen cage-free eggs, according to price data from the USDA.

Even if the price of cage-free eggs declines as they become the standard, Gregory said they will never be as cheap as today's regular eggs since labor costs are higher in cage-free farms and hens produce fewer eggs when taken out of the cage.

"All companies that have made public, cage-free pledges seem to be making their decisions based on brand perception, rather than current demand or scientific findings," Wells Fargo consultant Matt Stommes wrote in a report. "Since food and agriculture production is a low-margin business, until cage-free demand proves itself, it’s going to be tough to cost justify expensive changes to egg-laying chicken barns."

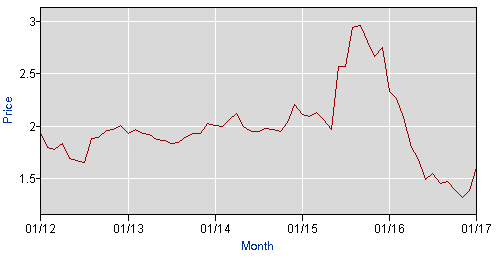

Two big problems stand in the way of the cage-free transition: First, egg prices are low right now, making big investments less attractive to producers. Even the country's largest egg producer, Cal-Maine Foods, saw net sales decline by about 57% and reported a loss in the six months ending in November. "The number of new cage-free projects has slowed down recently due to the current low egg price environment," Coit said.

Due to oversupply, at the end of 2016, Cal-Maine said the average selling price for regular eggs was down 64.9% year on year, while the average price for specialty eggs (like cage-free) was down 13.2%. Grocery stores ran more sales for cage-free eggs, according to USDA. Yet consumers opted for cheap, conventional eggs, not cage-free ones, said Coit. That pattern calls into question how much demand there is for the pricey alternative.

"This is a mess, and it all started because activist groups forced food companies to do this," said Gregory. "By and large, egg farmers are still in a state of shock, and definitely in a state of paralysis."

Egg prices recently tumbled.

Despite the uncertainty, animal rights activists are celebrating a major win for the movement. "The fact is that the largest egg buyers all have clear policies requiring their suppliers to stop locking hens in cages by 2025," Humane Society spokesperson Matthew Prescott told BuzzFeed News. "Unless egg producers want to lose business, they’ll simply need to convert."

The industry's transition ramped up in 2015 after McDonald's (which buys about 3% of all the eggs in the US) announced it would transition to cage-free eggs by 2025 "to improve the treatment of animals.” Walmart made the same commitment the following April, and months later grocery chain Publix said its egg selection would go cage-free by 2026. The rest of the food business followed.

Yet egg industry representatives claim builders and equipment suppliers will have a hard time keeping pace with these pledges. Some believe it simply won't work. "The 2026 deadline for 220 million hens to transition from conventional cages to cage-free is physically and financially impossible," said Gregory.

Not too long ago, the industry was very close to heading in a different direction. In 2011, United Egg Producers formed an unlikely partnership with the Humane Society to try to pass a federal egg bill that would transition the entire industry, by law, from conventional cages to "enriched colony" cages, which offer more space and amenities like perches, nesting boxes and scratching areas.

The cost for enriched colony housing would average out to $20–25 per bird, more than the $15 average for conventional cages, but still half as much as a cage-free system. The proposal was to make the industry-wide switch by by 2030.

The proposal didn't work, and the industry now faces a costlier transition.

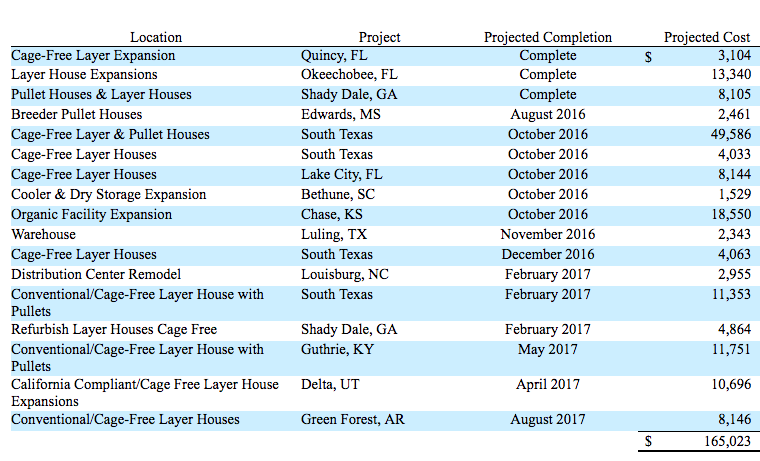

Cal-Maine Foods, which accounts for about a quarter of US egg consumption, broke out the projected costs of a number of cage-free projects in its last annual report, ranging from $3.1 million to $49.6 million. Cal-Maine also estimated its joint venture for 1.8 million cage-free hens will cost $73 million to build and start up.

Cal-Maine projects

An oft-cited case study is California, where voters banned battery cages in the state starting 2015. Not long after, Modern Farmer reported, "The legislature recognized that the law would put California egg farmers out of business, forcing them to spend lots of cash to upgrade their facilities while competing with out-of-state producers that weren’t subject to the regulation (and the attendant investments and price increases it would entail). So the law was expanded to cover all eggs sold in the state."

In effect, to guarantee the success of cage-free eggs, California had to make them the only option. By some estimates, the law caused egg prices to rise between 33% and 70%.

Still, the movement has continued to spread. In November, Massachusetts voters approved a ballot to prohibit the sale of eggs, pork, and veal from animals raised in small, confined spaces.

Activists say public opinion eventually overrides the difficult economics of the cage-free business. "At the end of the day," said Prescott, of the Humane Society, "the least profitable or economical type of product to produce is the kind no one will buy."