You might look at Coca-Cola's 7.5-ounce mini-can and shrug it off merely as a slightly smaller Coca-Cola. Shaving 4.5 ounces off the traditional 12-ounce can may seem like no biggie, strategically or physically.

Yet to Coca-Cola, each fewer ounce is a carefully calculated step into The Future.

As sales have declined, Coca-Cola — also owner of brands like Sprite and Fanta — has increased its marketing budget and launched sodas with fewer calories and new sweeteners. But "maybe the most important element in terms of our sparkling [carbonated beverage] portfolio has been the significant and strategic re-architecture of our packaging mix," said Sandy Douglas, the President of Coca-Cola North America, at a conference this week. The new mini-bottles and cans are "the way that we are reinventing" the soda business, he said.

That's a lot of enthusiasm for a small aluminum can. But what's significant about a Coke executive calling little cans and bottles — in other words, less soda — "a core part of our strategy" is the acknowledgement that the American market for soda indeed is getting smaller.

For decades, soft drinks have been seen as high-volume products that people consume frequently. Bottles gradually got bigger starting in the 1950s. Yet what was good for business eventually made calorie-packed sodas a major public health concern; consumers started to curb soda consumption. Coke needs to shift gears.

Enter the mini-can. Offering a downsized alternative to regular cans, is a notable, if also somewhat uncomfortable, decision for the brand. The smaller 90-calorie cans have been around since 2007 (nationally only since 2010), making them a fairly new addition for the 123 year-old company. And with 8.5-ounce aluminum bottles also in the lineup now, the company has added miniaturized alternatives to the 20-ounce plastic bottles commonly found in convenience stores.

Soda makers PepsiCo and Dr Pepper Snapple have their own versions of the downsized drinks.

Coke has reiterated the importance of these new sizes in recent years. As the soda maker said this summer in a blog post "whether it is our mini-cans or small glass bottles, we are better able to provide great-tasting refreshment in moderation."

But can the world's largest beverage company succeed if it embraces a philosophy of moderation?

As Americans drink less soda, the company is trying to roll with the trend.

One of the biggest challenges confronting Coca-Cola is that its main products are sugary drinks, which attract almost tobacco-level scorn among many health-conscious consumers.

It wasn't always that way. For most of it's long history, Coke had a rare, almost universal appeal that helped it dominate globally, available bottled pretty much anywhere on the planet. Coke reigned as the most valuable brand in the world for many years. It has been, in other words, an extraordinary product.

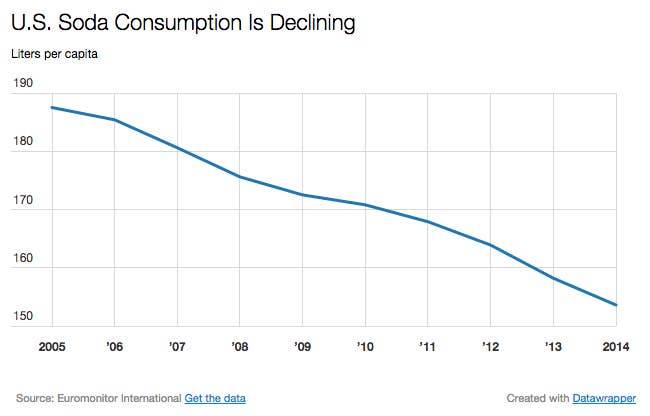

But a growing numbers of consumers are turning against not just Coke, but soda altogether. In a recent Gallup survey, more than six in 10 adults in the U.S. said they were trying to steer clear of the beverages. Public health campaigns have blamed soda for obesity and other health risks. Consumption of soda — including diet soda — has been declining for a decade, although it still averaged an impressive 40 gallons per person in the U.S. in 2014 — about 14 ounces per day.

As public opinion turns against it, the goal now for Coca-Cola is to keep soda in people's diets, even if it's in diminished portions. "Packages by the end of the 90s were all huge, and they were boring," said Douglas. Rather than waging a losing battle to persuade consumers to drink more soda, Coca-Cola's strategy has shifted to accepting that consumers — including kids — will drink less of it.

OMG, these are so 20th century.

"Smaller packages are re-recruiting consumers of all demographics, particularly upper-income consumers and particularly moms, because moms want to treat their kids, but they don’t want them to have too much, they want to be in control," Douglas said at the conference.

The company wants consumers to believe soda can be part of a healthy lifestyle, rather than antithetical to one.

This effort includes plenty of messaging, and not just via the company's uniquitous advertising. In March, the Associated Press reported Coke worked with a number health and fitness experts who had written articles published on blogs and newspaper websites saying small cans of soda could be a useful, portion controlled snack as part of a healthy diet.

"We have a network of dietitians we work with," Ben Sheidler, a Coca-Cola spokesman, told the AP at the time. "Every big brand works with bloggers or has paid talent."

In August the New York Times reported the company has also given significant financial support to a group called the Global Energy Balance Network, which argues Americans have paid too much attention to dietary causes of the obesity epidemic, and should also focus on boosting levels of physical activity and exercise.

Coca-Cola later disclosed hundreds of grants it made "with the best of intentions" for research, partnerships with medical groups, and community health programs over the past five years. The company decided not to renew some contracts due to "budget realities," reported the AP.

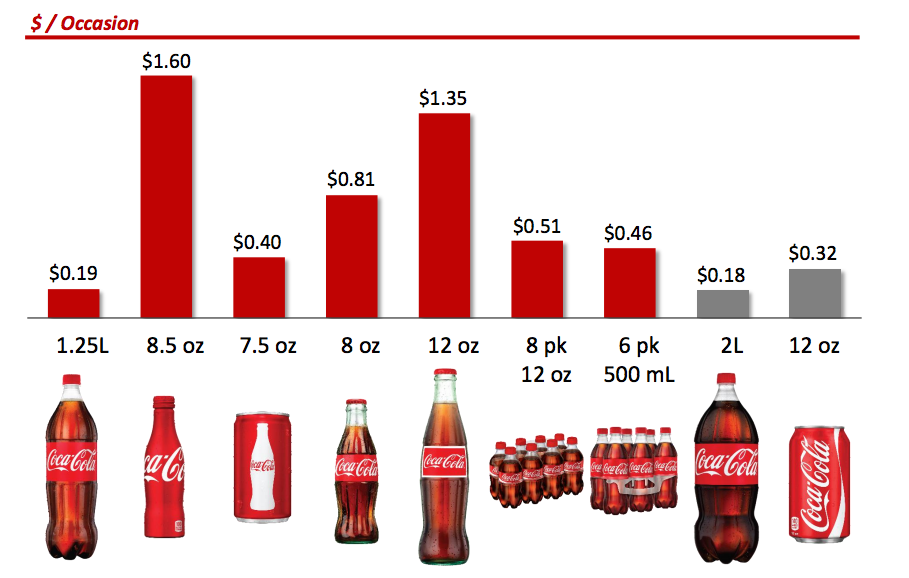

As its sales by volume decline, Coca-Cola is making up for it by charging more per ounce for the mini-cans and bottles.

The 7.5-ounce cans, for example, cost about $0.40 each while the larger, original 12-once can costs about $0.32. "A 12-ounce can traded to a 7-ounce can is a 30% reduction in volume, but it’s an increase in revenue," said Douglas.

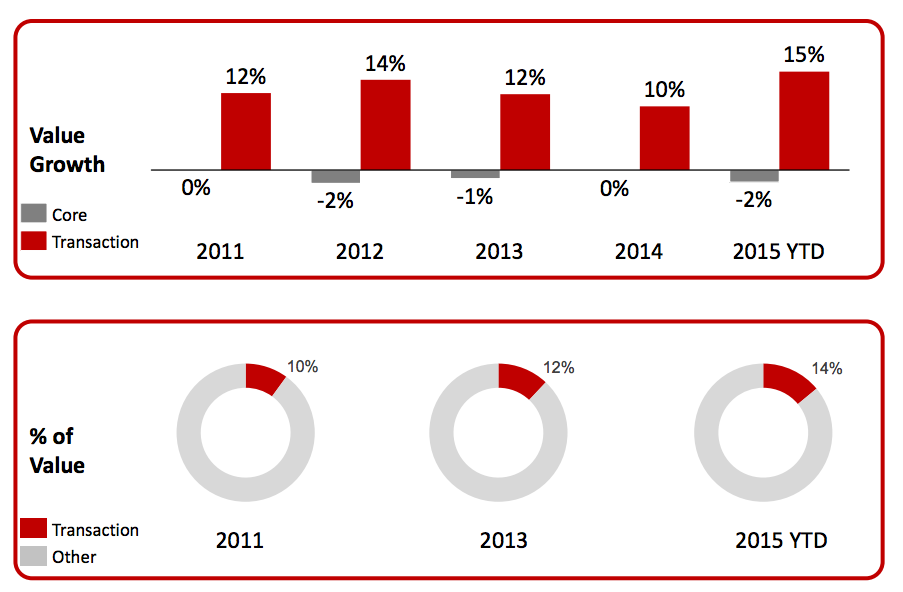

Coca-Cola says the strategy is slowly working. The old standard sizes — the 2-liter bottle and the 12-ounce can, which the company refers to in the chart below as its "core" packages — are in decline. Meanwhile, sales of the new smaller sizes, referred to as "transaction" packages because they encourage soda sales, have grown for years. They now represent 14% of sales compared to 10% in 2011.

"Gallonage is declining," Douglas said. The bright side, in a convoluted sense, is small sodas have "a lot of growth ahead," replacing many of yesterday's binge bottles one sized-down can at a time.