There’s never been a more organized movement to combat sexual assault on campus than the one happening right now, during fall 2017 orientation season. CONSENT IS SEXY, say the memey T-shirts sold across the country. Students arriving at dorms in their parents’ minivans drop their Kenmore mini-fridges in their rooms, lock mountain bikes to squiggly racks, and then perhaps check out early-evening showings of films like I Never Thought It Was Rape or It Was Rape. In front of the busy campus center, an upperclassman may hand out temporary tattoos or tubes of lip balm decorated with the number for a local rape crisis center.

But even as 18-year-olds are funneled through anti-sexual-assault seminars and sit cross-legged in common rooms watching films, there’s a dirty little secret lurking behind the scenes: There’s not much evidence that these programs actually work, I learned while researching them for my upcoming book — and for both financial and political reasons, what is perhaps the most promising program is barely taught on US campuses at all.

Broadly speaking, American universities offer three types of anti-sexual-assault programs, and the combination of all three can have some effect on changing the scene on campus. That’s about as much as you can hope for, because many students’ approach to sex and consent are already set by the time they reach college. According to the CDC, these programs need to begin far earlier, maybe in middle school.

A 2014 CDC evaluation of 140 sexual assault prevention strategies found that only three of them significantly reduced sexually violent behavior, and two of those were for middle and high school students. Since then, the CDC has only identified two more promising programs, including the University of Kentucky’s well-regarded Green Dot program — and Green Dot’s best behavioral results, once again, involve high school students.

And yet Congress has demanded that all college students receive sexual assault reeducation. “What the federal government wants us to do right now in college with prevention is an impossible task, and I don’t think anybody understands this,” says Brett Sokolow, the executive director of ATIXA, the largest Title IX officer group in the nation. “In a short four-year period, colleges are supposed to reprogram students? There’s no such thing. You can’t overcome every TV show they’ve watched and every movie they’ve ever attended, their friends’ beliefs, their parental attitudes.”

We should be a bit more optimistic — the three approaches I mentioned above could work as they get more developed and sophisticated.

The most popular type of programming, pioneered at the University of New Hampshire’s Prevention Innovations Research Center, is “bystander education.” It trains students to intervene when a situation looks troubling — particularly in places that adults won’t go, like cruddy frat basements. More abstractly, it encourages students to spread positive social norms and messages among peers. In many ways, the term “bystander education” might be considered code for “raising awareness.” This is noncontroversial, apolitical, and cheap. Universities like that.

The second type of programming, healthy masculinity seminars, is tricky. I will now introduce the term that scientists use when they talk about anti-sexual-assault programming: “dose,” meaning that they’re dosing kids with these ideas. A traveling band of masculinity gurus primarily administer these doses while promoting an idea that's essentially the reverse of bystander education: They tell college kids that men are the problem, and that only men themselves can make men stop raping. They demand that guys recognize their privilege and change their behavior.

The third type of programming is self-defense, and it's surprisingly out of vogue on US college campuses. “We teach almost 100 high school classrooms per year and less than five colleges," says Meg Stone, the executive director of Impact Boston, which brings self-defense to Boston public schools. "And it’s not for lack of trying.”

Even the language seems out of vogue: Harvard University’s Office of Sexual Assault Prevention publishes an extensive glossary of more than 40 issue-based terms, and while the list includes ”consent,” “rape culture,” and “patriarchy,” it does not list “self-defense.”

And yet, we know that the self-defense approach called “empowerment self-defense” has some good science behind it. One Canadian study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that a year after completing one of these programs, women were half as likely to be victims of rape, and three times less likely to experience an attempted rape.

Empowerment self-defense, which is taught in its fullest form in the US at the University of Oregon, doesn’t involve distributing rape whistles or cans of mace for students to grip in their palms as they walk home from the library. In some cases, it may not even involve that much actual physical self-defense. Students learn modified forms of self-defense from jiujitsu, but are also clued in to the reality of how they should escape a sexual assault — they have to shout, yell, or put their hands in front of them and firmly say “back off.” They learn that begging, pleading, or crying usually doesn’t get a victim anywhere. But they also learn that a key part of avoiding assault is not giving men the opportunity to assault them.

I understand why this is not a popular option in America today. When we start talking about opportunity and “women’s responsibility to stop rape,” questions begin to crop up that make everyone very uncomfortable. Does this mean women aren’t allowed to get drunk? Does it mean they should watch what they wear? But at the same time, we are doing a disservice to women if we don’t teach them how to spot red flags, which is part of empowerment self-defense.

Charlene Senn, the lead researcher on the Canadian study, has been awarded an almost $1 million grant further explore the program. Her system teaches freshmen to be wary of guys who try to control women, who speak negatively about them in general, or who purposely try to get them drunk or high. It theorizes that traditional gender-role expectations that some guys hold may mask inappropriate beliefs such as women “owing” men for buying them dinner. Such guys might insist on driving, might get angry when a woman wants to pay, and often interrupt when others, especially women, are talking. Be skeptical too, she warns, of a guy who is persistent in trying to get what he wants when he knows it isn’t what you want, even if the situation isn’t sexual. She also incorporates exercises to foster positive sexual self-image among students, a topic that schools like Columbia University have been studying as well.

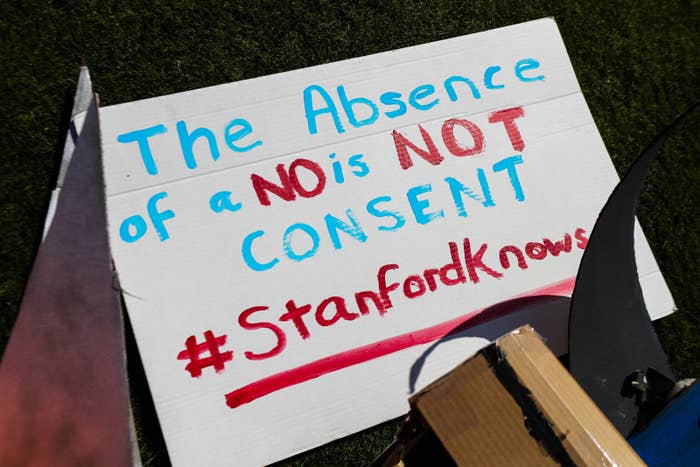

Right now, this program is only offered in the US at Boca Raton’s Florida Atlantic University, but Stanford University and its medical center have recently taken it under wing and should implement it soon.

A wider embrace of empowerment self-defense and other innovative programs in the United States would require a rethink of the prevailing approach, which is that men need to be retrained, not women. Many are skeptical of such a reevaluation — in the past, the CDC has said that this kind of risk reduction isn't a form of “primary prevention,” because if one woman fights off a man, he can assault someone else, and thus the overall risk of sexual assault won’t go down. But a CDC behavioral scientist, Sarah DeGue, told me this week that “there’s room for all these strategies.”

That sounds about right to me. We should think of empowerment self-defense as a way to achieve a short-term goal (women knowing how to protect themselves) and bystander intervention as a way to achieve a long-term one (raising awareness to shift long-standing social norms among a college population). And we should tell Congress to put money aside to rigorously test programs that they themselves have mandated.

“If we think of why sexual assault happens, it’s a combination of things — community norms that perpetuate it, people being apathetic and not taking bystander action,” and not teaching women self-defense, says Katie Edwards, a professor at the University of New Hampshire. “For me, from a science perspective, why not focus on all of these?”