In January 2013, a handful of sexual assault survivors from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill decided they’d had enough of how the prestigious public school treated rape victims. To fix the problem, they filed a complaint against UNC with the US Department of Education, sparking a federal investigation.

They haven’t heard much from that government agency since then.

The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights has more than 300 investigations open into how colleges handled sexual assault cases. While the agency says it strives to complete these investigations within 180 days, dozens of them, including the one at UNC, have been dragging on for three years or longer. And many of those students who filed complaints in 2013 and 2014 told BuzzFeed News they’ve gone years without any communication with federal officials.

With the investigations languishing, it leaves open the question of whether these schools are properly addressing sexual violence, and it delays reforms that may be ordered if the colleges are botching their responses to rape reports. The office responsible for the investigations is overworked, understaffed, and facing an uncertain future under the Trump administration, which is determined to roll back Obama-era policies and shrink federal bureaucracy. The sexual assault survivors who turned to the federal government for justice are now left wondering when — or if — they’ll see the outcomes of these investigations.

“They could just let them sit forever,” said one official who worked on OCR’s enforcement, noting that the agency doesn’t actually have deadlines to close the 311 current cases open at 227 campuses.

“Most people who do file a complaint while they’re in school will most likely either transfer, graduate, or drop out before their complaint is resolved,” Annie Clark, executive director of End Rape On Campus, told BuzzFeed News.

Clark is one of those people. She and Andrea Pino were among the group that filed the UNC complaint. The last time they heard from OCR was in 2013, when they declined a deal to cut off the investigation early if UNC agreed at that point to make reforms to its sexual assault policies.

“This is regular for a lot of complainants,” said Pino, who co-founded End Rape On Campus with Clark. “It's a shame.”

"They promised interviews while I was still on campus, but that never happened."

The US Department of Education declined to comment for this story.

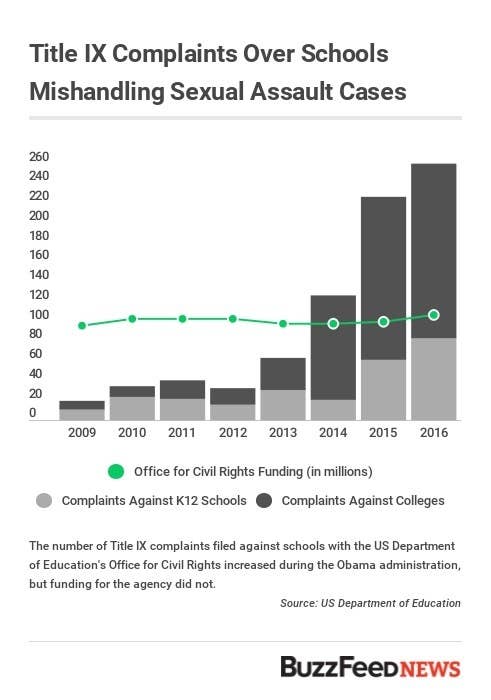

When the UNC complaint was filed, the women said they were determined to show that mishandling sexual assault wasn’t just a problem at their university — it was something happening across the country; and they did. Soon, students were showing each other how to file Title IX complaints with the Education Department. The number of these complaints jumped from 17 to 32 between 2012 and 2013, and then continued to climb to a record 177 last year. Many people expected these investigations to last about a year, because that’s how long the Office of Civil Rights took in similar cases in 2012.

The growing backlog hasn’t just frustrated the students who filed them, but the institutions being investigated as well.

When universities come under federal investigation, they’re bound to face scrutiny from state legislators, boards of trustees and regents, students and faculty, and prospective students deciding whether to spend tens of thousands of dollars to enroll. Clark said her group often gets calls from parents asking whether a school that’s not on the list is safer, a notion she tries to dispel.

“Schools typically who are on that list are looked at like they’ve done something wrong without any outcome yet from OCR,” said Kai McGintee, a higher-education attorney who has defended universities in sexual misconduct cases.

It’s unclear what direction the Education Department will take under the Trump administration on how it enforces the gender equity law Title IX. Many civil rights groups were angered that the administration quickly rescinded Obama-era guidance on how transgender students should be accommodated. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has not made clear how she might change the way her department handles Title IX investigations, and their fate depends on who gets appointed assistant secretary for civil rights at the department. It’s unclear when Trump will make his pick for the position.

Jennifer Reisch, legal director of the nonprofit firm Equal Rights Advocates, worries that when investigations are finished under the Trump administration, the results “won’t be as strong as it might’ve been under the previous administration,” a concern based on Republicans’ aversion to what they consider government overreach. For example, OCR may not demand extensive reforms, publicly call out schools when they have violated Title IX, or demand that colleges reimburse tuition and counseling costs for victims whose cases were mishandled — things the Obama administration ordered universities to do.

"The average time spent to wrap up an investigation grew from 289 days in 2010 to 963 days last year."

Each complaint can represent one or many students, and nearly a third of the open complaints were filed in 2014 or earlier, meaning dozens or even hundreds of complainants could be waiting to hear from OCR officials. BuzzFeed News spoke with students behind more than a dozen complaints filed more than two years ago, and all said they’d gone years without speaking to the OCR. Some have not even been interviewed by investigators.

Hope Brinn and Mia Ferguson, who filed complaints against Swarthmore in April 2013, said the last time OCR contacted them was in February 2014, and both have since graduated. “They promised interviews while I was still on campus, but that never happened,” Ferguson said.

The women who filed a complaint nearly four years ago against the University of Southern California also say they were never interviewed. One of them, Alexa Schwartz, asked OCR in January 2016 about the status of the case and was told it’s still ongoing — the same answer she got when she asked about it in March 2014. “I'm not sure what information they are waiting for at this point,” Schwartz said.

The family of a student who was raped at the University of Kansas said they haven’t heard from federal officials since July 2015, when they were told their complaint was being “fast tracked.” In the investigation of Harvard College, the lead complainants haven’t heard from OCR since it did campus visits in May 2015. Joanna Espinosa said she hasn’t heard from OCR since it told her the agency would open an investigation into her complaint against the University of Texas–Pan American in April 2014. The family of a student who filed a complaint against Iowa State University in 2014 hasn’t heard anything from the feds in over a year. The woman who sparked the investigation in 2013 at the University of Colorado Boulder finally heard this week that the evidence collection from the Title IX investigation there is done, and OCR officials are waiting on “management review.”

"I know they are absolutely inundated and swamped, and it's not going to get better with the new administration."

“I don't take it personally,” said Julia Dixon, who filed a complaint against the University of Akron in early 2014 and hasn’t heard from the department in two years. “I know they are absolutely inundated and swamped, and it's not going to get better with the new administration.”

Former OCR officials say it’s normal for there to be little communication between people who file complaints and investigators once a case is opened. But it’s unusual for so many cases to drag on for years, which makes the silence from the feds more infuriating to complainants. Department data shows the average time spent to wrap up an investigation grew from 289 days in 2010 to 963 days last year.

There are a few clear reasons why things are taking longer than they did previously.

When Catherine Lhamon ran OCR under Obama, she expanded all Title IX sexual violence investigations to become institution-wide, so investigators reviewed all cases at a school rather than just the cases that sparked federal complaints, former Education Department officials told BuzzFeed News.

Combined with a sharp rise in the number of complaints being filed, this “has strained and continued to strain the agency’s resources,” one former longtime OCR attorney told BuzzFeed News. This has caused many career staff to leave over the last three or four years, the former attorney added. As a result of the ever-growing workload, the former attorney said, “Morale has been really, really bad for the last several years.”

OCR got a 7% budget increase at the end of 2015, allowing it to hire 49 more officials — not all of them investigators. But the OCR’s staff includes 51 fewer people than it did a decade ago when the agency received about half as many complaints. One investigator who left an OCR field office last year told BuzzFeed News “you couldn’t really feel the difference,” because the volume of complaints kept growing. Overall, these type of complaints grew by 1,170% during the Obama administration, partly because the White House widely advertised filing them as an option for students.

“Unless new [employees] are added, the backlog of unresolved cases will grow, frustrating students and, in many cases, jeopardizing their access to education,” OCR warned in a report for Congress last year, as the agency sought more funding. The number of cases each investigator takes on has almost doubled since 2006, OCR’s report noted.

President Obama tried last year to get OCR more funding to help clear the backlog of Title IX investigations, but was largely unsuccessful. As President Trump now prepares a budget that is expected to include cuts to the Education Department, hope of getting more funding for OCR has diminished.

It’s unclear how much these federal investigations cost colleges. The closest available data comes from a report by the insurance firm United Educators, examining 305 claims reported from 104 campuses between 2011 and 2013. It found those schools collectively spent close to $5 million defending themselves in OCR investigations, but that was before the probes became more expansive.

“It’s an extraordinarily time-consuming and costly exercise to comply with a OCR investigation — not to mention the negative press with being under investigation by the federal government,” McGintee told BuzzFeed News. “No college wants that.”

In May 2014, over the protests of higher education officials, the department began disclosing what’s sometimes called a “shame list,” showing which colleges are under Title IX investigations. But now schools are growing frustrated that their names seem to hang there in perpetuity.

“The underlying issue is not that there is a list itself — it’s the criteria of how an institution is put on, and how they get off and comply with federal regulations is not clear,” said Makese Motley, a lobbyist for the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. “They should not be on the list for years at a time.”

Colleges are often left in the dark by federal officials while an investigation is ongoing. There's usually a flurry of activity early in an OCR investigation, when colleges are asked to provide documents and data. Investigators might conduct on-campus interviews, but otherwise, they rarely have direct contact with a school until an investigation is completed, regardless of how long that takes.

Title IX investigations wouldn’t take as long if they focused on individual complaints rather than institutional failings, as OCR often did under the George W. Bush administration. But that would be a “terrible move,” argued W. Scott Lewis, a higher education consultant with the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management.

"They could just let them sit forever."

“Even when you get the singular complaint, you have to determine if this was a systematic issue,” Lewis told BuzzFeed News. “Frankly, that’s how civil rights investigations should be. I need to know if this problem is a larger problem, or if this is an anomaly. And even if it is an anomaly, you still have to fix it.”

To close out cases quickly, the department could simply say that no violation occurred or that the school already had changed its policies to comply with Title IX, according to two former OCR officials. Or it could let cases linger indefinitely, since the investigation manual doesn’t provide a timeline for staffers to follow. “They can have a case that stays open for 10 years if the administration chooses to do nothing about it,” said a former OCR investigator.

It’d be a mistake if the department chose those routes, and decided to essentially drop investigations, argued Clark, of End Rape On Campus.

“It would be moving our nation backwards,” Clark said. “Instead of trying to eliminate discrimination, it would be almost enshrining it.”