RIGA, Latvia — Dr. Viktors Kalnbērzs still remembers the day in the winter of 1968 when the phone in his office rang and changed his life forever.

On the other end of the line was his friend Vladimir Demikhov, a pioneering transplantology surgeon, who told him about a potential patient named Inna.

“A woman came in who wants to change her sex,” Demikhov told him, using language and revealing attitudes about gender transition that were commonplace at the time. “She wants to become a man.” Demikhov wondered if Kalnbērzs would be interested in taking on the patient.

Kalnbērzs would risk the anger of Soviet authorities and being shunned by the medical community to carry out an unprecedented surgery that remained a state secret for decades.

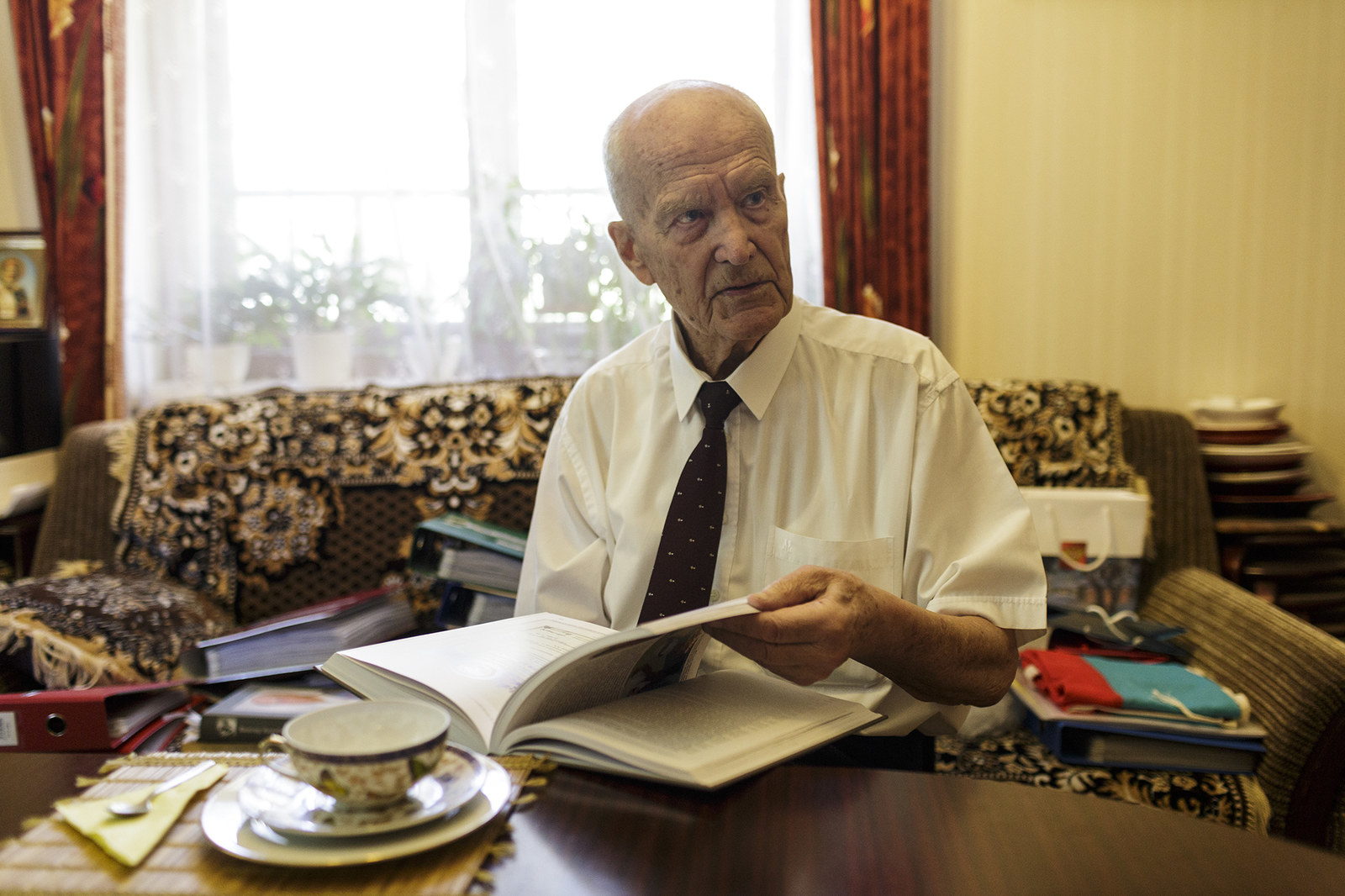

More than 40 years later, BuzzFeed News and Russian website Meduza tracked down Kalnbērzs, now in his nineties, to a sleepy suburb of Riga, the Latvian capital, where he spoke for the first time at great length about the world’s first full female-to-male gender affirmation surgery.

Kalnbērzs was known for performing operations creating penile prosthetics following accidents, injuries, and burns. He had also operated many times on patients with both male and female external genital characteristics.

At the time, Kalnbērzs thought he would never understand why someone would want to change their sex, and he recalled asking himself if he’d “bring the wrath of God on himself” for performing the surgery. “I was deeply conflicted,” he said, 40 years after the fact. He worried what the patient’s mother would think. “I was afraid that I was somehow going against nature, against God.”

“I know you’re going to try to talk me out of it, but don’t bother.”

Nonetheless, he agreed to meet with Inna at the Riga Traumatology and Orthopedics Research and Development Institute, a two-story brick building on the outskirts of Riga, where he worked. Today Latvia is an independent state and a member of the European Union, but at the time it was the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic and part of the Soviet Union. Kalnbērzs described the person he met a few days later as a “lively brunette with markedly feminine features.” Inna was only 30 at the time and worked as the director of a research and development institute in Moscow.

“I know you’re going to try to talk me out of it, but don’t bother,” Kalnbērzs recalled Inna telling him. “I am convinced that nature has made a mistake and that you can fix it.”

Kalnbērzs said he asked Inna about experiences with sex. Inna found sex with men repulsive and had tried everything to overcome the feeling, from hypnosis to hormone therapy, and nothing helped. Inna appealed for help to doctors in Moscow, but said it ended in them “giggling.” The surgeon promised he’d think about it and Inna returned to Moscow.

After this initial meeting, Kalnbērzs began researching, but there wasn’t much information available. All he could find was scientific literature regarding just four transition operations from female to male. But not one of the operations had been fully completed — the old sexual organs had been left intact, still functioning, alongside the new sexual organs created by the surgeons. The patients could get pregnant and they still menstruated.

The person widely believed to be the first to successfully undergo female-to-male sex reassignment, more commonly referred to today as gender affirmation surgery, was Michael Dillon. By all accounts, the transition was not complete: In one medical journal, a letter from his surgeon described the patient as a “hermaphrodite with an intact female genitalia,” and even Dillion referred to himself as a hermaphrodite in his memoirs.

After reading all the literature, Kalnbērzs made a momentous decision: If he were going to carry out the surgery, he needed to do it fully, and to the end.

Inna eventually returned to Riga. Kalnbērzs said he could not guarantee success but would allow Inna to watch how he operated on intersex patients and decide how to proceed. He gave Inna a white nurse’s coat and told other patients that the person in the nurse’s coat was a consultant who would assist with hormonal therapy. After seeing how Kalnbērzs operated to construct a sexual organ, Inna was ready to go ahead with the procedures.

Once Inna was admitted into the hospital, Kalnbērzs called together a group of surgeons and psychiatrists to decide how to proceed. The conversation was rooted in the thinking of the time. One said hypnosis would not be effective in Inna’s case and the only option for Inna to live a happy life was to go ahead with the sex reassignment surgery. Another said that if Kalnbērzs didn’t perform the surgery, it was possible that Inna would attempt suicide. No one in the group objected. The health minister of Latvia, with whom Kalnbērzs was friends, gave his verbal permission for the operation to go ahead.

"I will never get over it if I were to lose my child.”

At that point, Kalnbērzs asked to be introduced to Inna’s mother. Inna agreed, and arranged for the two to meet when the doctor was visiting Moscow for a term at the Academy of Sciences. Kalnbērzs recalled Inna’s mother telling him that Inna had already attempted suicide three times. In one instance, Inna’s mother was able to call an ambulance in time to save Inna, but was afraid that, if there were a next time, she might not be so lucky. “I can come to terms with my daughter becoming my son,” she said. “But I will never get over it if I were to lose my child.”

Kalnbērzs also consulted with priests. One of them told him that “one must not interfere with the word of God,” while another reasoned that “if nature made a mistake and you fix it, you are helping the Lord.”

Kalnbērzs recalls a bizarre incident in which one of his colleagues attempted to change Inna’s mind by trying to convince Inna to fall in love with him. But according to Kalnbērzs, “his efforts ended in total failure.”

However, in another indication of language and views — widely seen as outdated and offensive in the West — persisting from Soviet times to the present day, Kalnbērzs maintains that the episode involving Inna and his colleague became a meaningful argument for him to carry out the surgery, because, Kalnbērzs said, “If a woman failed to fall in love with him [the colleague], she was not a woman and therefore, it was justified to turn her into a man.”

Despite all this, at a certain point, Kalnbērzs decided he would not take on the operation after all and asked Inna to return to Moscow. In response, Inna wrote him a letter in 1969:

From my earliest childhood, I lived with the firm conviction that I was a little boy and that this little boy would, with time, become a man. This conviction existed before I could even know it and it came out in every little thing I did. As the years passed, it grew, and it grew so strong that the seeds of my masculinity ended up predetermining my entire future. Despite the appearance of feminine sexual characteristics, purely masculine inclinations, habits, affections, and aspirations developed inside of me, and gradually coming to isolate me from others, depriving me of the ability to have friends, to have people close to me, to have a family, and everything else that everyone else takes for granted.

When I was 12, it was time for my first love, and the object of my affections wasn’t a he — it was she. This feeling, which persisted until I was 18, was the first to reveal to me, with a cruel clarity, that my situation was hopeless. Essentially, this was the beginning of a serious reflection on the terrible issues I had, which somehow had never bothered me up until then, and hadn’t yet forced me to think about myself.

Time passed, and at first, a purely chivalrous inclination instinctively began to search for a way out, but there had never been one, and there never could be. Having gradually withdrawn into myself, I have nevertheless tried. I have desperately tried to change who I am, to overcome myself, to suppress my attraction to women. But all of these attempts have proved futile. I will never be attracted to men even while, fully aware of the hopelessness of my situation, I have tried with all of my might to suppress any manifestations of the masculinity inside of me. The only thing that I have managed to achieve over the years is my practically theatrical performance of femininity. But even in this, I have, by far, not always been successful. The way I think, my psyche, and therefore, all of my behavior, all of the tiniest particularities of my character and even the smallest nuances of my personality, plus, everything that I care about — which is to say my whole inner life, is completely shaped by my masculinity, and constantly hiding this is unspeakably hard. I live like a spy on enemy soil, except my life is even harder: the spy at least knows that in time, someone will come and take over for him, and he will again become himself, while for me, there isn’t and can’t be any hope that one day someone will relieve me of the necessity of living forever behind a mask; from constantly playing the role that I hate; from wearing the clothes that disgust me, from having neither friends nor family; from being afraid of being myself even when I’m around the people closest to me.

On top of all this, my constant and powerful attraction to women significantly complicates my life. It’s a passion that finds almost no outlet, whose unending, unrelieved build up makes life unendurably torturous. If my only option is intimacy with men, I might as well hang myself.

I’m 30. What has formed in me constitutes the foundation, the basis of my entire life. Even if some kind of miracle could make me feel attracted to men, it would be completely impossible for me to suddenly, in the fourth decade of my life, remake my entire life and learn to be interested in purely feminine pursuits, taking up feminine habits that I have only vague notions of. In addition to all of this, I have a firm, long-standing affection for women that I would finally like to provide me with the opportunity for basic human happiness.

Considering everything I have written here, and knowing that you are carrying out a similar experiment, I am pleading with you to help me get out of this. If a full reconstruction is impossible, I ask that you at least give me plastic surgery and allow me to legally change my sex. Please give me the opportunity to live at least some of my life in harmony with my inner needs, not shunned as an outcast, but as a human being among men.

Inna’s letter appears to internalize views put forward by Kalnbērzs that people would find unacceptable today, and seems to conflate being attracted to women to being trans — in a further indication of the way homosexuality was viewed in the USSR in the ’70s.

But after reading the letter, Kalnbērzs finally agreed to proceed with the surgery, many months after he received that first phone call from his surgeon friend. Inna, who traveled back to Riga from Moscow, asked Kalnbērzs to keep the procedure confidential out of concerns that she would be harassed by the government and secret police. Inna was placed in a separate ward away from other patients, but the nurses gossiped and many of the other patients and their relatives wanted to look. Some of them would open the door to Inna’s room and then apologize, pretending that they had come in by mistake. Inna lay in the hospital bed, head covered with a blanket.

Kalnbērzs operated on Inna nine times. “I did it so that if she was unsatisfied with the results, everything could just be scrapped and she could remain a woman,” he explained. At one point he decided to call in a gynecologist to help. When she saw that there was nothing “wrong” with Inna, the gynecologist refused to participate in the operation, calling it “criminal,” and saying that she would end up behind bars if she were to assist him. And so Kalnbērzs did that surgery himself as well.

The entire process took over a year and a half. The first operation was performed on Sept. 17, 1970, and the last was completed on April 5, 1972. They had to take breaks for two to three months at a time to allow Inna to heal. During those months, Inna would return to Moscow, continuing to work as normal.

“Innokenty wore pants, made a habit of visiting the garage, where he befriended the hospital drivers. He liked to swear, smoke, and get drunk with other men.”

“I falsified the documents for her sick leave so that no one would find out about the operations. I wrote that she was getting plastic surgery for correcting certain defects, but nothing about changing her sex,” Kalnbērzs said.

After the final surgery, they began calling Inna “Innokenty” — the name stuck at the hospital, but the patient chose another, secret name after leaving. As far as we know, Inna used female pronouns before surgery, but afterward was known by male pronouns, another outdated method of referring to trans people’s identities by today’s standards.

“He wanted to emphasize his masculine appearance, to stand out with his masculine behavior; after hormone therapy, his voice had deepened,” Kalnbērzs recalled. “Innokenty wore pants, made a habit of visiting the garage, where he befriended the hospital drivers. He liked to swear, smoke, and get drunk with other men.”

Kalnbērzs helped Innokenty change his documents, something that had to be approved by a Latvian SSR committee that included representatives from the regional offices of the interior and health ministries. The committee asked Innokenty how he felt. He said he was very happy, Kalnbērzs recalled. Innokenty was issued a new passport, a draft ticket, and other documents.

“I feel that I have the strength to catch up on everything I missed in my previous life.”

Kalnbērzs said he would rather not know too much about his patient’s new life for fear of accidentally outing him. So he gave Innokenty his contact information and asked him to stay in touch.

In parting, Innokenty gave the doctor a note, dated Aug. 14, 1972: “Finally, after so many years, the duality that was oppressing me is gone. In my new form, I can be among people as my legitimate self.

“I feel that I have the strength to catch up on everything I missed in my previous life,” he wrote.

Kalnbērzs worried that his colleagues would judge him for having performed the operations on Innokenty and that he would fall afoul of the Soviet health ministry — and he was right.

During Soviet times, LGBT people were considered criminals, and any doubts about sexuality regarded as debauchery.

For transgender people, the approach was haphazard. Some patients were able to change their gender on their documents; others were diagnosed with schizophrenia and treated with psychotropic drugs or put into institutions, sometimes for their whole lives.

Andrei Snezhnevsky, one of the founders of Soviet repressive psychiatry, often deployed against dissidents, called transsexuality a “perversion” in his 1983 book and would diagnose transgender people with schizophrenia.

Other psychiatrists, like Aron Belkin, believed in gender reassignment surgery and became one of the first psychiatrists in the USSR to issue permissions for such operations on a regular basis. The doctor believed that “changing a person’s sex was lofty and humane, helping an individual not only liberate themselves from a situation that was torturous for them, often leading to suicidal actions, but also allowed them to find their true place in society,” as he wrote in his book The Third Sex.

When the Soviet health minister, Boris Petrovsky, got wind of Kalnbērzs's undertaking with Innokenty a few days before the patient was due to be released from the hospital, he demanded that Kalnbērzs travel to Moscow immediately and explain himself. Kalnbērzs made the trip and found a grim bureaucrat waiting, who said he was already in contact with the Ministry of Justice about Kalnbērzs.

“Do you realize that your actions were criminal?”

In his memoirs, Kalnbērzs recalls a lengthy exchange between the two men — one that puts the episode at the heart of the Soviet Union’s vision of itself, as a place far from the decadent, sexual West.

“Do you realize that your actions were criminal?” Kalnbērzs recalls Petrovsky asking him. He recalls the minister saying that “this kind of surgery goes against the Socialist regime” and that he belonged “behind bars.”

Kalnbērzs told the minister he was only hoping to help a patient that he feared was “on the verge of suicide.” The minister replied by saying the patient should have died, calling the operations “perverted.”

“Transsexuality isn’t [a] perversion,” Kalnbērzs says he told Petrovsky. “It’s a disease.”

“There is no such disease,” the minister replied. “It’s pure perversion and you are facilitating it. Are you aware of what’s going on in capitalist society? In Japan, they are advertising free sex. Do you want that to happen here?”

He then began to rant about how homosexuality was illegal in the Soviet Union and accused Kalnbērzs of trying to get it legalized.

“This kind of operation does not belong in our society,” the minister continued. “They would support you in the capitalist world. Our society must protect its citizens from harmful operations. This is experimenting on humans!”

In the end, the minister did not move to jail Kalnbērzs but delivered a “severe reprimand,” saying he had performed a damaging operation that went against Soviet ideology.

Kalnbērzs was banned from performing such operations in the future and talking about them in lectures or writing articles. A notice about the ban was sent to every regional office of the health ministry throughout the Soviet Union. For the next 20 years, Kalnbērzs's breakthrough remained classified.

Trans people still face immense problems in modern-day Russia, where a rise in conservative attitudes, particularly concerning gender and sexuality, is being stoked by the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Trans people face violence, job insecurity, and difficulty getting documents. In its 2018 Rainbow Europe report, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association placed Russia 45th out of 49 countries for LGBTI human rights. Russia’s Center For Independent Social Research said last October that hate crimes against LGBT people in Russia had doubled in five years in the wake of a law banning “gay propaganda.” And in 2015, Russia listed trans people as among those who would no longer qualify for driving licenses.

Though a decree issued in February by the health ministry simplified and accelerated the process for changing one’s gender on a passport, many still face barriers to getting the sort of medical treatment they may need.

Few doctors perform female-to-male gender affirmation surgeries, and those who do require patients to receive special permission issued by medical committees, which are constantly under attack from conservative activists. The most likely committee in the country to grant such permission, at the St. Petersburg State Pediatric Medical University, was dissolved in 2015, after the Russian Orthodox activist movement Narodny Sobor successfully campaigned to have its director, the psychiatrist and sexologist Dmitry Isaev, fired. Dozens of people from around the country had come to see him — both for his reputation and for his prices. Isaev would charge 10,000 rubles ($160) for an examination, compared to the fees of 30,000–70,0000 ($475–$1,100) other committees would charge. Today, Isaev gives private consultations. In Moscow and other cities, these kinds of examinations are performed in psychoneurological clinics, but few people are willing to turn to them for fear of being forcefully hospitalized or diagnosed with schizophrenia — a fear from Soviet times.

In order to grant permission for sex reassignment surgery, a doctor must diagnose a patient with “transsexualism.” The latest version of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), released June 18, no longer lists gender identity disorder under “mental and behavioral disorders.” The changes in the ICD-11 are important first and foremost symbolically, but the disappearance of transsexualism from the list of disorders will mean that new regulations will have to be written for prescribing hormonal and surgical treatment.

Russia will have to use the new ICD, but the process of incorporating it into the existing medical practice is long. The previous version, ICD-10, which came out in 1990, only began to be implemented in Russia seven years later.

Despite the reprimand from the Soviet health ministry, Kalnbērzs went on to have a brilliant career in medicine.

He was finally able to register a report of his innovation — “a method for surgical treatment of hermaphroditism” — with the Soviet committee on inventions and discoveries in 1975, in which he detailed a complete sex reassignment operation. The report was only available in secret archives, but was published fully in the early 1990s. And, despite the health ministry ban, he performed a handful of sex reassignment surgeries that coincided with the reform movement of perestroika in the late 1980s at a time of increasing freedom.

In the 1980s, he spent several years on the front line in Afghanistan, where he operated on wounded Soviet soldiers. He treated one of the leaders of the KGB for impotence. In the 2000s, after he had retired, he received letters of gratitude from President Vladimir Putin.

"Until the end of my life, I will consider you my god.”

As for Innokenty, he was in touch with Kalnbērzs sporadically after his surgeries. Seven months after his final operation, he sent Kalnbērzs a letter, saying, “I am just living my life and working like anyone else. At the same time, it’s not quite that simple. Other people live by rules that tell them to live like life is a race, chasing after success. For me, this chase no longer exists. I look at life and value the kinds of things that probably only old people value — life itself. The internal struggle between the two selves that had raged inside of me used to cut me off from the entire world. Until the end of my life, I will consider you my god.”

Innokenty said he had quit his job at the research and development institute and decided to end his career in engineering, believing the KGB — whom most people regarded as all-seeing — would be interested in his past. He’d tell doctors that his scars were from a fight. “A surgeon never figured out that his penis was artificially constructed. At that time, it wouldn’t occur to anyone to think that sex change operations were being performed in our country,” said Kalnbērzs.

Innokenty lived in Riga for a while before leaving for Siberia, where nobody knew about his past.

After moving to Siberia, Innokenty continued to call the doctor every few years. He called him “professor.” Every time, it would be from a different phone number. Even decades after his operation, Innokenty remained afraid of the KGB and other secret police organizations.

Kalnbērzs said Innokenty got married in the late 1970s. He recalls his former patient saying, “The woman had been with other men before me, men who were much more masculine than me — I’m no match — but she says that she has never been as happy with anyone as she is with me. My unwavering potency and tenderness is among the most important, if not the most important, reasons for that.” But the woman soon died of cancer. Innokenty went on to marry again.

Kalnbērzs said he wasn’t particularly keen to know about all this. He thought that he’d done his job and the patient should now live his life. In the 2000s, Innokenty offered to meet on several occasions to discuss their lives. Kalnbērzs would find excuses to avoid meeting him. He didn’t want to talk about the past, but most of all, he was afraid of facing his former self. “I won’t see that patient; instead, I will see an elderly man,” he said. “And that will force me to look at myself in a new light. A person doesn’t always want to be seen in their pitiful state.”

According to Kalnbērzs, the last time Innokenty called was in the winter of 2017. He wanted to know whether the doctor would perform one more operation on him — a prophylactic one (the patient was now nearly 80 years old). The surgeon answered that he had retired a long time ago and couldn’t operate because of his back. Plus, the hospital where, 40 years earlier, Innokenty had had his first surgery, was long gone. In parting, the patient wished Kalnbērzs good health. BuzzFeed News and Meduza attempted to find Innokenty, but were unsuccessful.

Kalnbērzs, now 90, has, for the past nearly 20 years, lived in a house built on the fees he received for performing surgeries in Europe and the US. It’s in a quiet suburb of Riga that the local papers call “the village of millionaires.” His house stands next to a pine forest and a river. On the first floor, Kalnbērzs has made a museum dedicated to his work. It is mostly photographs where the doctor appears next to famous people: military commander Semyon Budyonny, former Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev, singer Laima Vaikule, and others. Next to these photos hang portraits of Lenin, Stalin, and Putin. On a nearby shelf, there is a pink ceramic penis. ●

You can subscribe to Meduza's newsletter here.