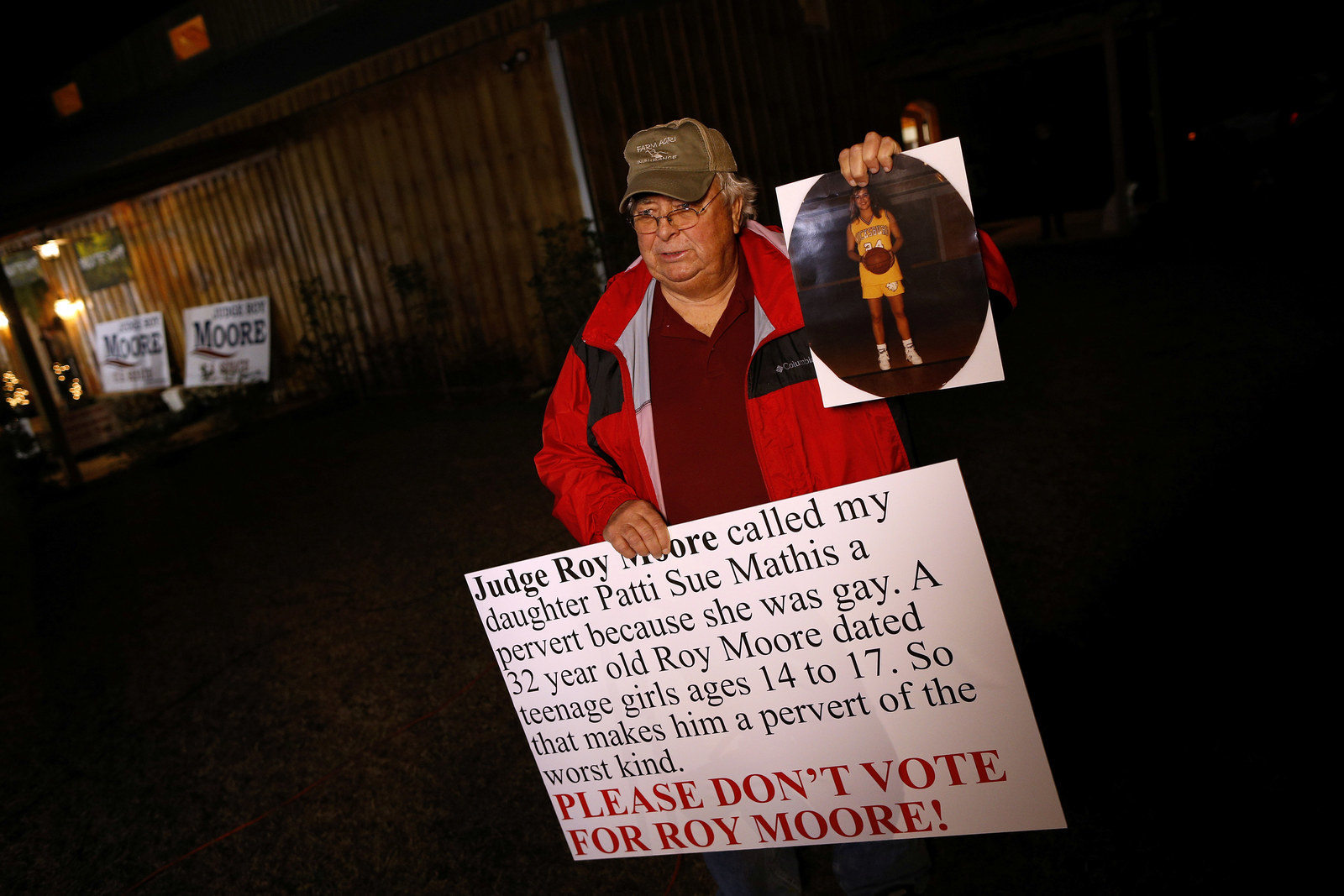

Last December, Nathan Mathis stood alone outside a barn in Midland City, Alabama, where a Roy Moore rally was taking place. Wearing a red windbreaker and a green Farm Agri Insurance cap, he held a sign and a picture of his daughter, Patti Sue, in her yellow basketball jersey. Patti Sue, a lesbian, had killed herself in 1995 at age 23.

To get past security, Mathis had folded up his sign so no one could see what it said: “Judge Roy Moore called my daughter Patti Sue Mathis a pervert because she was gay. A 32-year-old Roy Moore dated teenage girls age 14 to 17. So that makes him a pervert of the worst kind. Please don’t vote for Roy Moore.”

To get to the barn, he had to walk a quarter mile away from the main road, down an unlit path through the pine trees. Inside, his neighbors cheered for Moore, the Republican candidate for Alabama’s special Senate election, who as a judge had removed children from a lesbian mother’s custody and called for a ban on “homosexual conduct.” Moore aimed to replace Jeff Sessions, who’d left his Senate seat to become attorney general, in the next day’s election. Twenty feet away from Mathis, Steve Bannon spoke to reporters.

“I was afraid I was gonna get knocked in the head,” Mathis remembered months later from the driver’s seat of his maroon Dodge Ram. We were driving through south Alabama, past acres of bushy green peanut plants early in their 135-day growing season, while helicopters from the nearby military training school cruised overhead.

Mathis had almost been late for the rally because the first print shop he contacted refused to make his sign. Then the friend who’d said he’d accompany Mathis backed out at the last minute. So Mathis, 75, a retired peanut farmer and former Republican state legislator, drove the 14 miles to Midland City, past Dixie Horse and Mule Co. and more churches than you can count on one hand, until he reached the barn, where rallygoers took photos next to a life-size cutout of Donald Trump.

Midland City, the town of 2,344 where Mathis was born, is part of the Wiregrass region of southeast Alabama, southwest Georgia, and the Florida Panhandle, named for the tough native grasses that used to cover the area. Wiregrass protected quail, rabbits, and other small animals from predators, but after years of farmers plowing over it, there’s not much left.

Mathis spent only about 20 minutes at the rally before the property owner asked him to leave, but it didn’t take long for images and videos of him to go viral. Media swarmed him at the rally, and three days later, Ellen DeGeneres flew him to Los Angeles to appear on her show. The country watched Moore lose to Doug Jones by just under two percentage points, sending an Alabama Democrat to the Senate for the first time in 25 years.

“I didn’t think I had done any good, that night when I came home,” Mathis says. But letters poured in thanking him — “two or three thousand,” he estimates, some from overseas.

My usually snarky queer newsfeed filled up with crying emojis and links to the Ellen interview. Mathis, on a dark winter night, in the face of possible violence, stood up for his daughter in an uncommon act of courage. What stood out about Mathis wasn’t just that he supported LGBT rights like few straight white men of his generation. What’s rare and compelling about Mathis is that he transformed his grief into tangible solidarity, putting his body on the line for queer and trans people.

Lane Clemons, 29, a gay Wiregrass native who had organized a Handmaid’s Tale–themed counterprotest up at the main road at the Moore rally, didn’t hear what Mathis had done until a day later. He’d been scrambling to turn 20 donated red tablecloths into red cloaks for the protesters after months of campaign work for Doug Jones. “When I read about it, it tore me all the way apart,” Clemons said.

Mathis did not swing the election for Doug Jones; that credit should go to the 98% of black women who voted against Moore, and a frenzy of statewide organizing. What he did instead was show queer and trans people what it looks like when straight, cisgender parents of queer children who say they care about LGBT rights actually do something about it — something of particular importance now, when the murder rate for all LGBT people is up, our basic rights to exist in public free from violence are in jeopardy, and Justice Anthony Kennedy’s departure from the Supreme Court could endanger them even more.

Even though almost 9 in 10 Americans know someone who is queer or trans, anti-LGBT legislation continues to pass around the US. Kansas and Oklahoma voted this year to allow adoption agencies to discriminate against LGBT couples, and the House just advanced a federal version of the same bill. In neighboring Mississippi and Florida, during the last legislative session, a total of 11 proposed laws to protect LGBT people died in committee. And a major champion of discriminatory laws is now vice president: In 2016, Mike Pence tried to pass six sweeping anti-LGBT bills as Indiana governor, despite national backlash on similar legislation the year before.

The numbers don’t seem to line up: Voters with queer or trans people in their lives are still electing politicians with anti-LGBT records.

Mathis was just one person trying to change that in December. I went to visit him in Alabama to find out what turns a grandfather into a force for change and whether any groups were capitalizing on Mathis’s moment to galvanize parents of LGBT people to political action. I didn’t find much national support for such a movement. Instead, I met straight parents working like hell to make sure the next generation of queer and trans youth survive the South, where it’s tough to find a trans-friendly doctor and teachers can’t “promote homosexuality” in sex ed lessons. I also found defiant LGBT people like Clemons scratching out a path for themselves in their hometowns, with and without their families of origin, resisting the narrative that says they should leave for someplace more progressive but much less like home.

At Tennessee Valley Rocket City Pride in Huntsville, Alabama, in mid-June, where a lesbian pet store owner handed out rainbow chew toys and the North Alabama Democratic Socialists of America sported rainbow rose buttons, Mathis reclined in a lawn chair in the shade, greeting cheery, mostly youthful attendees in their teens and twenties. Pastor Madge Atkinson, who leads Unlimited Ministries, an LGBT-friendly church housed temporarily in a hotel outside Huntsville, had invited him to speak at a service and attend his first-ever pride celebration. She’d brought coolers of water and Coke for the long day under the blazing sun, where anyone who wanted to could go up to the open mic and talk to a few hundred attendees scattered among 50 booths.

The Grissom High School Gay Straight Alliance sold hand-painted wooden mini flags representing a spectrum of identities: aro, pan, bi, lesbian. They’d crafted everything at 17-year-old Lily Bottomlee’s house; her mother, Larkin Rice, who helped staff the booth, had been thrilled to host them. What moved Rice about Mathis was his transformation. “It was heartbreaking to hear that it took something that drastic to change his mind,” she said, choking up.

Mathis’s message, post-Moore, has focused more on urging parents to accept their kids than on politics. “You people who’ve got gay children and grandchildren, don’t mess up like I did,” he says. At Pride in Huntsville, those children and grandchildren, dancing to Lady Gaga in rainbow lipstick and pride flag capes, were still managing a lot of pain.

“When I first came out to my mom, the first thing and really the only thing she said was, ‘I will always be disappointed in you,’” said 21-year-old Cas Martin, who was attending her first Pride. Ducking under a pop-up canopy to escape the sun, Martin told me she wouldn’t have been able to come without the ride she got from her friend Monique Hebert, whose daughter belongs to the Grissom GSA.

Hebert, hovering near Martin at the Grissom GSA booth, said she thought it was important to bring her. “She needed to come here and see what support looks like,” Hebert said. Later, as the sun set behind the lawn stage, Martin giddily lined up to put a dollar in a drag queen’s bra.

All afternoon, queer, trans, and genderfluid young people collected in clusters under the cool-off tents and sucked on fancy ice pops in flavors like raspberry cream, which were for sale at the brewery next door. They were eager to tell me about struggles with their own parents, most of whom were not in attendance.

Lawrence Haliburton, in a spaghetti-strap white tank top and tattoo choker, has seen his mom call out anti-gay comments in front of him, but he hasn’t come out to his dad, and neither of his parents has taken political action for LGBT rights. If they did, “It would mean the world to me,” he said. “Doing anything would just be a big step for either one of them.”

His friend Shana Smith, 24, watches RuPaul’s Drag Race with her mom, but her dad “is always making gay jokes and using slurs,” she told me. He’s grudgingly accepting of her sexuality, but not of anyone else’s.

The bar is low for how LGBT youth are treated at home, because at-home oppression is still so common. More accepting parents may extend support only to their own child, like Smith’s dad. Maybe they wouldn’t kick their kid out of the house, but they wouldn’t abandon a politician who voted against that child’s rights either.

“I have a low expectation of what I want my mom to do,” said Jasmine McIntosh, 26, who took proud photos for Instagram in rainbow sunglasses. She was a newcomer to Unlimited Ministries, seeking queer community in Huntsville. “If she was out there with me trying to push for LGBT rights and all that, I’d be overwhelmed.”

In the humid flats of south Alabama, where gnats buzz around anything that moves, you can catch bream, shellcracker, and catfish from April through July at Lake Patti Sue, which opened in 2015 in honor of Mathis’s daughter. Gators cross over from Buzzard Bay, rippling the surface between a stand of skinny trees in the northeast end of the lake. A not-quite-functional boat called the Naughty Lady is permanently docked in front of the lake house, where Mathis and his wife, Sue, spend most weekends.

Mathis is a talker, an acceptable form of vulnerability within the confines of Southern masculinity. On the drive down from Montgomery, Alabama, he told me in a no-nonsense drawl about a popular football player killed in a car crash with his children, a woman who was eaten by an alligator and whose arm was later found in the autopsy of the animal, and the two girls discovered dead in the trunk of a car whose murders were never solved. Death is a common theme in his stories, maybe because he’s lost both his children; Patti Sue’s older brother Joey overdosed on Oxycontin in 2004, nearly a decade after Mathis’s daughter died.

“It took me a while to be where I could talk about it,” he said at the dining room table in the lake house after I’d arrived, the air conditioning on full blast. In the meantime, he drank. “There’s a while there where you don’t care if you live or die.”

Then, in 2010, he started building Lake Patti Sue, an artificial lake on 70 acres that would take him five years. The physical labor helped him heal. Now he brings his daughter up in conversation whenever he gets a chance, like on our pit stop at Julia’s Restaurant, when he invited tired cooks on their lunch break to visit the lake before sitting down to fried okra and greens. “I can’t keep it bottled up,” he said.

Another acceptable way to expose your vulnerability is to speak from the pulpit on a Sunday, and Mathis did that too, at Unlimited Ministries in Madison, Alabama. Pastor Atkinson had forgotten it would be Father’s Day when she’d booked him to talk about gay rights at the church, which holds its services in a ballroom at the Country Inn & Suites until it can find a more permanent home. There’s no sign for the church out front, so I had asked workers setting up continental breakfast inside how to find it. They gladly directed me down the hall, and I noticed how relieved I was that the organization was called “Unlimited” and not the “Super Gay Church of Alabama.”

It’s not a gay church, per se, and plenty of straight congregants show up, like the mother of a 5-month-old baby who couldn’t stomach the anti-gay sentiment at another local church since her own mother is married to a woman. Atkinson founded Unlimited Ministries a year ago when she and other gay members of her local church were told they could attend services but were not allowed to take on leadership positions. That didn’t fly, so Atkinson began leading her own Christian weekly service for about 25 worshipers.

Atkinson, tall and welcoming with a practiced confidence in front of a crowd, played a blue acoustic guitar in a pale blue button-down, serving Indigo Girls comfort in a deep Alabama accent. Her wife, Natalie Johnson, had set up a camera to livestream the service featuring Mathis’s sermon on Facebook Live. “People watch when they’re working the drive-thru at Hardee’s,” Johnson said.

The congregation was ready for Mathis’s sermon. In it, Mathis was candid about his mistakes. “I regret very much the mean things I said to Patti when I found out she was gay, and I realize now there was nothing wrong with Patti. Something was wrong with me,” he said. Mathis brought an onslaught of biblical evidence, citing 17 verses, from Philippians 2:12 to Luke 6:27, to counteract what everyone in the audience had heard about the evils of homosexuality, either from their parents who filled pews across town or pastors who spent whole sermons on why gay marriage should be illegal.

More than a few people wiped away tears when Atkinson played “You’re a Good, Good Father,” the most benevolent song about patriarchy I’d ever heard. Brad Ploof, who will marry his boyfriend in Unlimited’s first wedding this month, was awed by Mathis’s presence. “I found myself hovering around him yesterday, kinda like you do your dad,” he said. “God is using him in amazing ways.”

Sara Dunn comes to Unlimited every Sunday with her husband, Eliot Stegall, who transitioned last summer. Dunn, 35, who’d had her nails painted black with rainbow dots in honor of the two-year anniversary of the Pulse nightclub shooting, lost custody of her kids when she came out during her divorce from a straight cis man. “The term ‘crazy lesbian’ was thrown around the courtroom,” she told me after the service, as churchgoers stacked chairs and packed up the keyboard in the ballroom. She is still not allowed to see her children for overnight visits and had to celebrate her 7-year-old’s birthday a few days early when it was her visitation time. She and Stegall had “been through hell.”

But Dunn was hopeful. “There’s a real fire in Alabama right now,” she said. She and Stegall volunteered for Doug Jones’ winning Senate race, and Dunn jumped in on the Poor People’s Campaign. That momentum after Mathis’s action felt like a beacon of hope among churchgoers who hadn’t always felt support from their families of origin. Stegall, who has worked for College Hunks Hauling Junk and Moving since before his transition, had dressed up for church in a button-down and tie. After the service, in a hallway between the hotel vending machine and the indoor pool, he told me Mathis’s sermon was “a glimpse at what I wish that I’d gotten from my own grandfather.”

Finding out that their child is queer or trans should ideally turn family members into advocates, and for some parents, it’s an easy jump. Lynne Starnes, a member of Indivisible in Huntsville, showed up to Pride on her own, awaiting her son Chase’s arrival from Nashville among other Indivisible volunteers. She grew up with right-wing parents but calls herself “a blue dot in a red social group.” When Chase came out five years ago, she said, “I did not consider myself an activist, but that day I became one.” After Doug Jones’ win, she decided to volunteer for Peter Joffrion’s pro-LGBT congressional campaign.

There isn’t real momentum in the movement to organize potential allies, but their votes have real consequences for the queer and trans community. PFLAG, the most prominent national nonprofit organization focused on them, has been trying to change that. With roots in activism, PFLAG began in 1973 as the Federation of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays after founder Jeanne Manford’s gay son Morty was hospitalized after being beaten at a protest. She wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Post criticizing the police, who watched the beating without intervening, marched alongside her son in that year’s third-ever New York City Pride march, and later convened a group of parents at a West Village church to connect. Forty-five years later, the organization focuses on “support, education, and advocacy” to fight for LGBT equality.

When Mathis appeared on the national news at the Moore rally, members of the PFLAG National staff watched him in awe just like I did. “I thought, if he isn’t already a PFLAGer, he must be on his way,” said Liz Owen, PFLAG’s national communications director based in Washington, DC. But no one from the organization reached out to him; a journalist ultimately connected Mathis with a chapter in Birmingham. Owen told me a slight majority of PFLAG members are actually LGBT themselves, rather than “parents and friends.” Nick Wilbourn, the gay president of the Huntsville chapter, told me many of his members are LGBT people seeking advice on how to come out to their parents.

With over 400 chapters across the country, including nine in Alabama, PFLAG is stretched thin. The website offers online materials for legislative visits and a how-to guide for advocacy, but the national office in DC responds to requests for support rather than organizing actively. “We do not hover,” said Diego Sanchez, director of advocacy, policy, and partnerships at PFLAG National. He could not share how many PFLAG members testify in public, write letters to the editor, or appear at statehouses, because he said the organization does not have the funding or staffing power to track those numbers.

Indeed, the national organization spent more money than it brought in the last two years and fired its executive director in March after only six months on the job, along with the national director of financing.

Owen would not comment on the firings except to say “PFLAG is strong, thriving, and constantly working in the world to make this a diverse, inclusive place we want to see.”

Nathan Mathis went to the Moore rally out of a deep personal drive, not because he was connected to an advocacy group. But most parents of LGBT people don’t have his innate confidence or political awareness, and they’re not getting much political support from the national organization built to serve them. Plus, they face possible social isolation should they stand up for their queer or trans children. Mathis knew exactly how many of his neighbors disagreed with him: “They voted for Roy Moore about 10 to 1, almost.”

Those risks are minimal compared to what it’s like to be queer or trans in a small town, however. Hank Miller, a gay member of PFLAG in Dothan, Alabama, came out in the ’80s, when he says he and his friends couldn’t get served at Hardee’s because they were gay and two men couldn’t rent an apartment together. “I wound up several times with stitches,” he said. This was the kind of environment that Mathis’s daughter Patti Sue didn’t survive.

Mathis also struggles with his own guilt about his relationship with his daughter when she was still alive. “We patched things up,” he told me. “I honestly believe that from the bottom of my heart. Still, I did wrong, you know.”

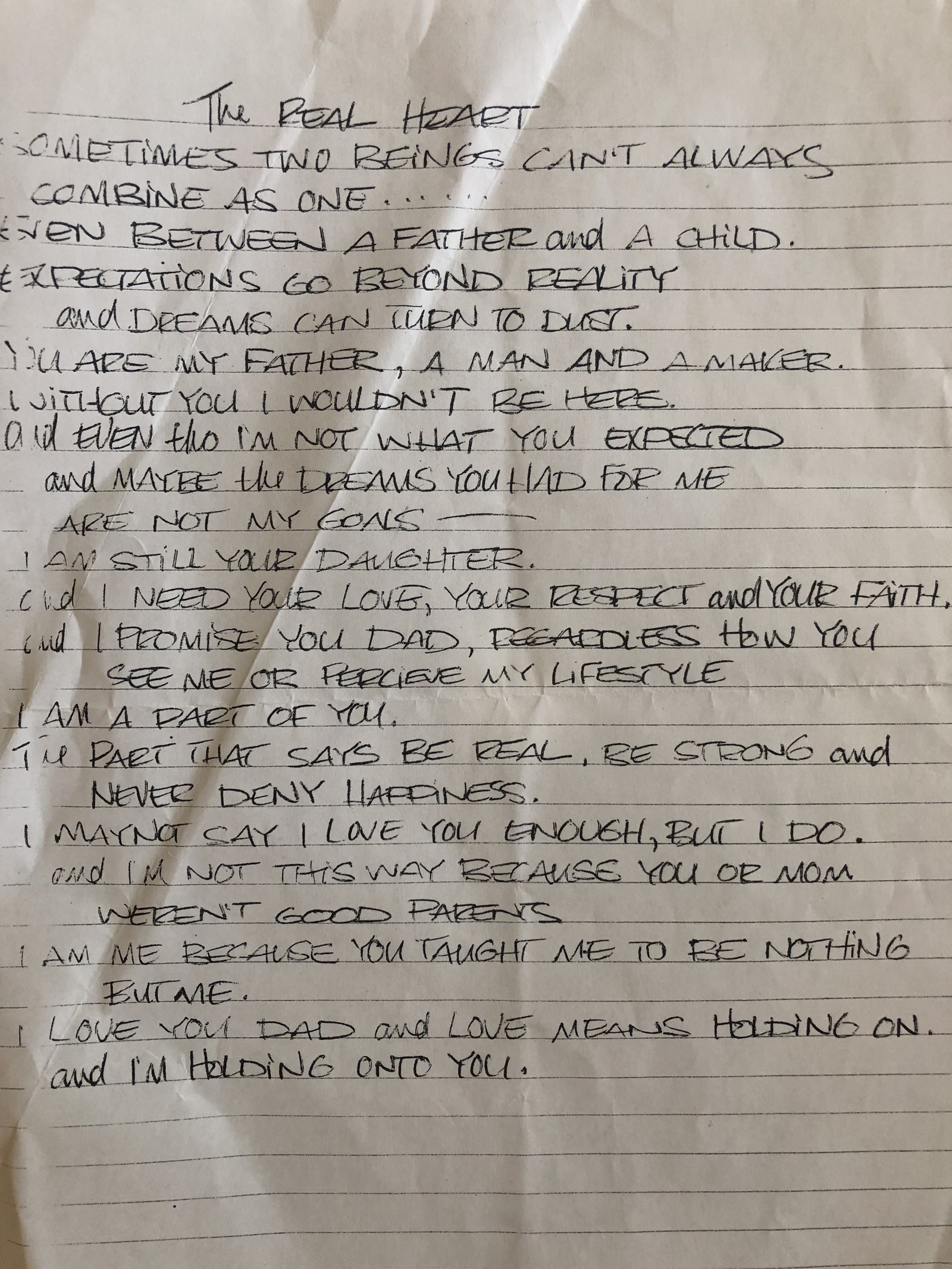

During his sermon at Unlimited Ministries, Mathis shared a poem Patti Sue had given him on a piece of notebook paper, where she tried to explain herself in block-letters. “I’m not this way because you or Mom weren’t good parents / I am me because you taught me to be nothing but me. / I love you Dad and love means holding on.”

But for some LGBT people, a parent’s bold political action might smack of hypocrisy, especially following the betrayal of familial homophobia. Laura Binford, 24, a lesbian from Dothan, was reluctant to celebrate Mathis because she’d heard rumors of how badly he’d treated his daughter when she was still alive. “It’s kind of hard to be like, ‘Heck yes, Nathan Mathis,’” she told me at Dothan’s only coffee shop. But Binford admired his bravery, and she does want other parents to take a stand. “Nothing’s gonna happen if we all just talk about how much we love gay people,” she said.

For Justin Vest, the parent of a 7-year-old trans daughter in Montevallo, Alabama, working for LGBT rights is “an opportunity for folks to reclaim their family.” Parents of LGBT youth like Vest have an immediate interest in making Alabama an easier place to live. He and his wife advocated to make sure their daughter, Nico, who socially transitioned when they lived in Maryland, felt comfortable at school.

I met him at his home in Montevallo, a suburban single-family house indistinguishable from the others that lined their leafy street. On the inside, however, Shepard Fairey posters and a “Feminist Drive” street sign decorated the walls. Vest, in a yellow “Destroy the gender binary” T-shirt, saw a clear role for parents like him and his wife. “I don’t want to put my kid out there as the one who has to fight for change and be the poster child [for trans rights] because I feel like in some ways that’s not fair,” he said while his younger child chattered through her pacifier on his lap. Vest started a group called Hometown Action, which organizes around issues like health care and education in rural parts of Alabama.

Montevallo, a university town just south of Birmingham, passed an LGBT nondiscrimination ordinance in April after a two-year fight. It’s the second nondiscrimination ordinance in the state; Birmingham passed one in September 2017, though by February, the city had not yet created a commission to enforce it.

Small towns “should be places where everyone can live and be accepted and have an opportunity to thrive,” Vest said. That includes his trans daughter, but it also includes parents like him, who can find strict gender norms stifling in their own lives.

Vest isn’t sure Nico understands the weight of the nondiscrimination ordinance, and he’d prefer that she stay sheltered from as much anti-trans sentiment as possible. But she’s picked up on his activism. The day I visited, she’d drawn him a Father’s Day picture with a little blue, pink, and white trans flag. Beneath it she wrote, “I’m glad you are proud to be my daddy,” the PROUD in blue, pink, and white block letters.

With or without their parents, in Nico’s Alabama, queer and trans people are resisting the narrative that tells them they have to leave the towns they grew up in to be safe. In other parts of the country, better laws may protect LGBT rights, but superficial “tolerance” can mask bigotry right below the surface. The challenges of the Deep South, in contrast to milquetoast acceptance elsewhere, can forge a deep commitment to change.

“There’s almost an element of defiance for me in claiming my home,” Dana Sweeney, 23, told me. I met him and two other young queer volunteers from Hometown Action at K.C. Vick’s house in Montgomery on a sticky Sunday night. Though all three had helped out with the Doug Jones campaign, only Sweeney had heard of Nathan Mathis, whose appearance at the Moore rally had hit him “like a sackful of bricks.”

Sweeney, who’d just returned from a weekend in Atlanta, presented Vick with a coffee mug with a quote from activist Grace Lee Boggs on it: “The most radical thing I ever did was to stay put.” In the upstairs bathroom, someone had scrawled “magic is your birthright” in marker on the mirror. Sweeney traded stories of recent arrests with his friend Travis, 33, who asked that his last name not be used.

“To be blunt,” Travis said, “Alabama still has a long way to go.” A stocky black Iraq veteran in a “No Justice, No Peace” shirt, Travis has known he was bisexual since he was “knee-high to the age of 5,” but when he came out to his mother at 19, she didn’t believe him, and she still doesn’t. Travis spent 12 hours in jail in May after a white anti-abortion activist accused him of harassment when he used an umbrella to shield a woman entering an abortion clinic. Sweeney, who is white, spent three hours in jail with Vick’s grandmother for blocking traffic as part of the Poor People’s Campaign. They’re organizing alongside both their chosen family and families of origin, whomever they can convince to step up.

Vick, 29, in a royal blue pencil skirt and perfect lipstick with a cat curled on her lap, has a tattoo of Alabama on her left shoulder. “It’s a selfish thing. I want to live a good life here,” she said.

Sweeney, a slender Keith Haring lookalike in wire-rimmed glasses, came out to his family after the 2016 election — “I’m not as straight as you think I am!” he announced at Thanksgiving — and then to his entire southwest Georgia hometown in a letter to the editor of the newspaper after his state senator cosponsored an anti-gay adoption bill. His mother, who’d initially asked him not to talk about his sexuality out of fear for his safety, wrote her own letter to the editor the following week, affirming her son and asking readers to vote the senator out.

The organizers I spoke to at Vick’s apartment are door-knocking and phone-banking and taking selfies on the state Capitol steps with a mixture of fearlessness and realism. “We don’t have a choice,” Sweeney said. “It has to be better, and it doesn’t get better on its own.”

Inside the lakehouse June 18, Sue Mathis made peach ice cream for about 20 Dothan PFLAG members, who had gathered to present her husband with a courage award. The group, a mix of LGBT people, parents of LGBT people, and friendly locals, focuses mostly on support and friendship, not on political action. As an ambitious national organization, PFLAG may be wavering, but its chapters are still providing a valuable resource.

The Dothan chapter has been a boon for Amanda Bynum, who cried through every meeting at first. She lost her faith community when her son, K.B., 20, came out as trans and Assemblies of God leaders said he could no longer help her teach kindergartners in the youth ministry. K.B. said he lost all his friends, but he comes to every PFLAG meeting.

The chapter members ate pulled pork, coleslaw, and peanut butter pie as the sky darkened over the lake. After accepting his award, Mathis bestowed chapter president Sam Maddox with a handsome box set of the Bible on CD.

Instead of an afterparty — the G Spot, a laundromat/gas station/drag bar in town, was closed — Lane Clemons, who had organized the Handmaid counterprotest at the Moore rally, held court on the deck in front of Patti Sue’s now-darkened lake, where citronella candles barely deterred the gnats.

Lisbeth Ash, a Houston transplant who watched her husband’s patients fight AIDS in the ’80s, had brought a cake with PFLAG piped across the top to the meeting. A longtime chapter member, she’s sometimes hesitant to speak up about LGBT rights because she’s straight, though she loves the meetings. “I don’t have that voice. I can’t tell that story,” she said from a deck chair.

But she’s already advocating in her own way. When she paid for the cake, the cashier asked what the letters stood for, and Ash explained, handing out Human Rights Campaign business cards from her purse, while the cashier and bagger listened with interest.

Clemons interrupted. “You don’t know how much that does matter,” he said. He’d blocked his father on Facebook the night before, weeks after losing his grandmother, a champion he called “Ganny,” to liver failure. “We have to have help,” he said. “We’re doing it on our own.” ●

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. For LGBT-specific services, the Trevor Lifeline is 1-866-488-7386. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org.