A major new study on pay gaps in Britain has shown that while differences in income between various groups have narrowed in the past few decades, women, people from ethnic minority backgrounds, and disabled people are still paid less on average than their counterparts.

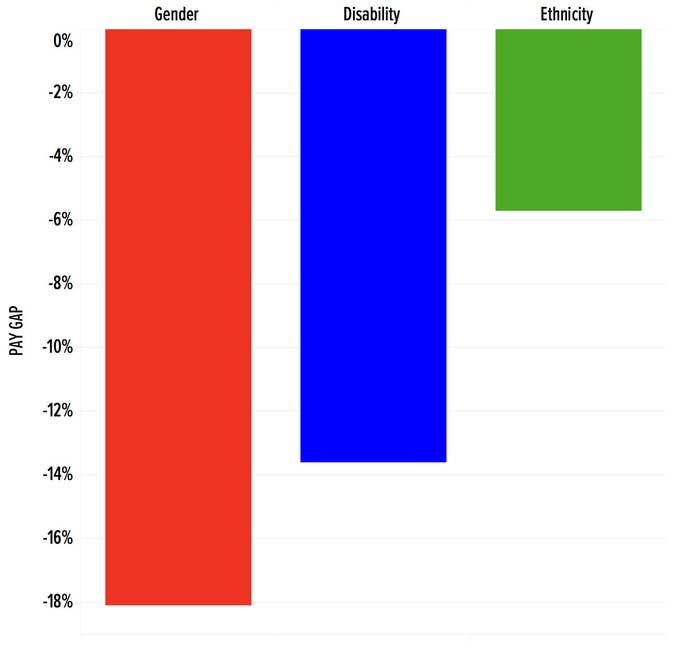

The research found that, on average, women still earn 18% less per hour than men, disabled people have a 13.6% gap compared with nondisabled people, and people from an ethnic minority background earn on average 5.7% less than white people.

However, the research from the Equality and Human Rights Commission also paints a complicated picture – including that in recent years, the gender pay gap has reversed in London, and that white women on average earn less than women from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Here are some of the key findings:

Gender

While the gender pay gap across all working women was 18.1% in 2016, that goes down to 9.4% for women in full-time work. Part of the reason for the gap is that more women work part-time than men, and part-time work tends to pay less per hour.

Though the gender pay gap has decreased significantly in the past few decades, the percentage of that pay gap that can’t be “explained” by different characteristics of men and women in the workforce (such as differences in type of work they do, level of education, and childbearing) has increased.

One significant reason for the gap used to be that women tended to have different occupations to men – however, this has declined notably in recent years. Almost all of the overall pay gap is now taken up by differences in pay within the same occupation, meaning women either hold less senior jobs in those occupations, or are simply paid less for the same work.

Between 1993 and 1997, around half of the gender pay gap was “unexplained”, while in the period 2010 to 2014, the unexplained portion had risen to almost 69%. That unexplained pay gap could be down to factors that the researchers weren’t able to factor into their analysis – but it could also be due to simple discrimination.

Researchers found that while pay gaps were larger for women with children, they existed even for women without children – and that the amount of housework a woman does also has a significant effect. For example, women who do more than 10 hours of housework a week experience a larger pay gap per hour than women who do less housework. (Twenty-four per cent of women in the sample did more than 10 hours a week, compared to just 5% of men.)

Women do far better in the public sector than in the private sector, even after you take into account that a higher percentage of women in the public sector are graduates – which tends to reduce the pay gap. Women in the private sector earn on average £3.11 less than men in the private sector; women in the public sector earn £2.38 less. For graduate women in the private sector there is only a small improvement, earning £2.77 per hour less than male graduates, while in the public sector the gap for graduates decreases to £1.63 per hour.

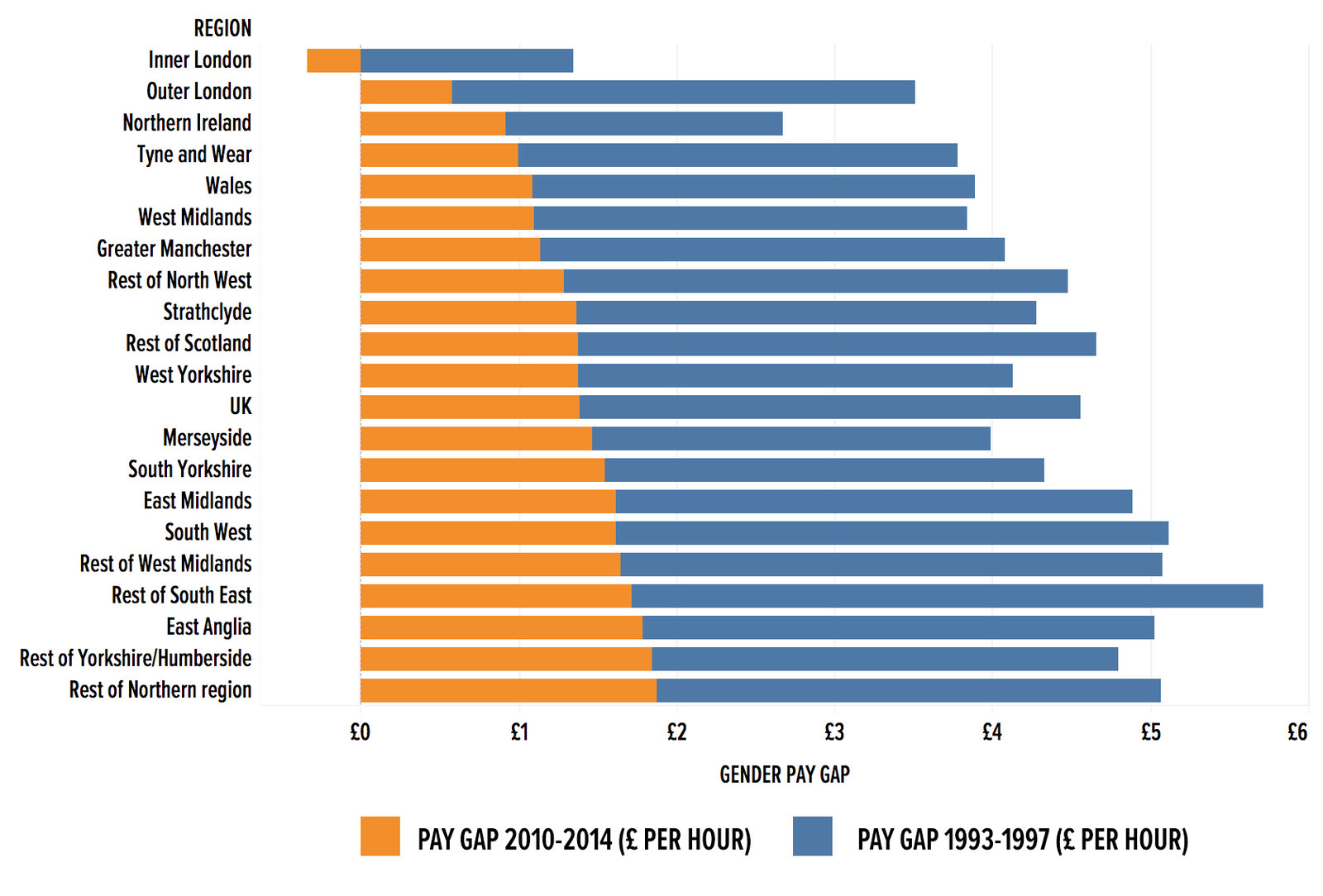

The researchers also found a major “London effect”: Living in London dramatically reduces the pay gap for both women and ethnic minorities. This is so significant that the study suggests that in recent years, women working in inner London actually reversed the pay gap, earning slightly more on average than their male counterparts. (The researchers do note that other recent research hasn’t shown the same effect, though.)

Ethnicity

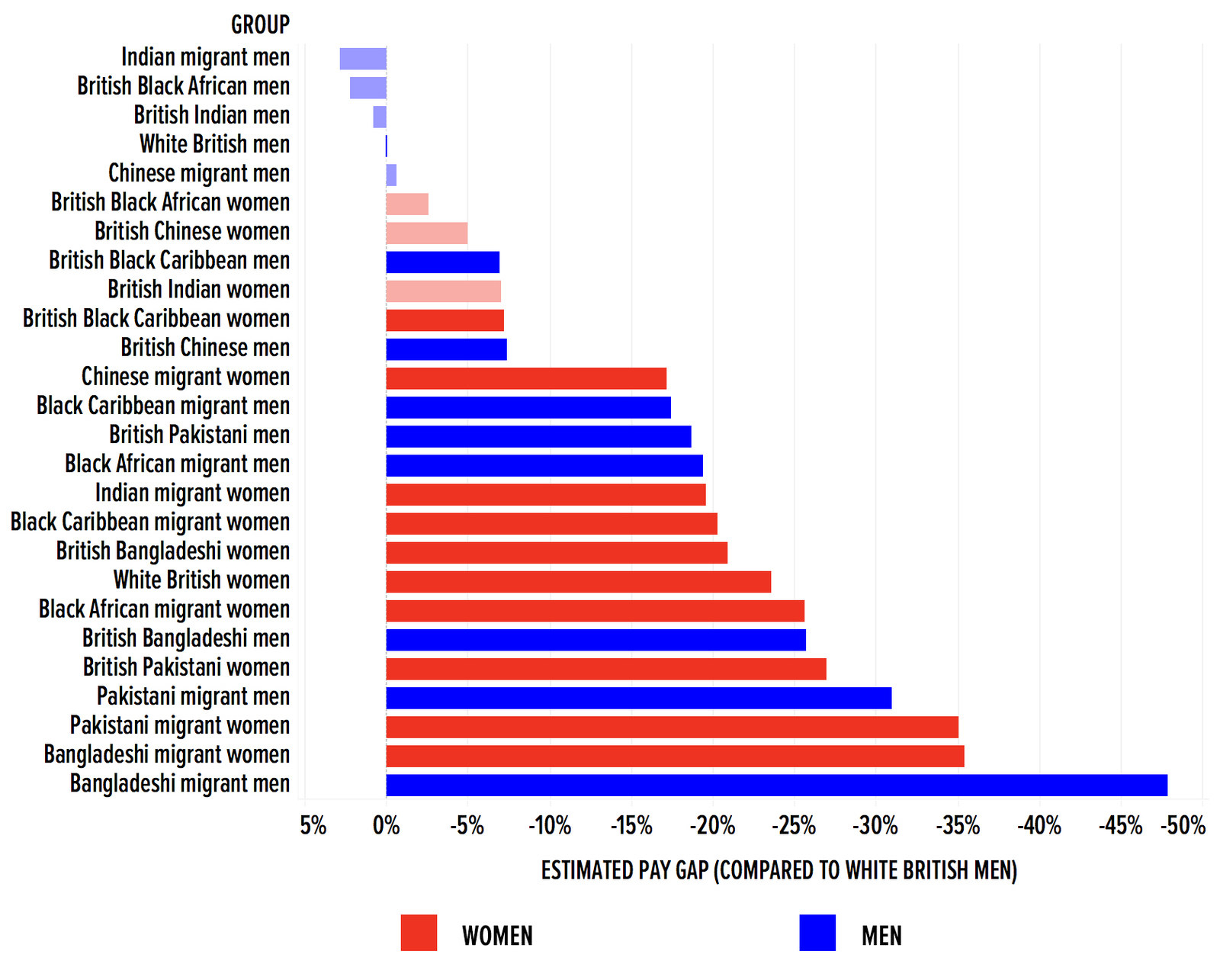

The research shows a complicated picture for the ethnicity pay gap. There are significant differences between people with different ethnic backgrounds, and the gap is far larger for men than women.

Indeed, on average, ethnic minority women earn slightly more than white British women – Black Caribbean women earned £1.14 per hour more in the period 2007-2014, Chinese women earned £1.29 more, and Indian women earned 59p more. (They all still earn less than white British men.)

Only a few groups had pay roughly equal to white British men – including Indian men, black British-African men, and Chinese immigrant men. None of the differences between these groups and white British men are large enough to be statistically significant.

The gap is almost always worse for immigrants compared to those who are born in Britain. For example, while black African immigrant men earn around 19% less per hour than white British men, men born in the UK with a black African background earn about the same as white British men.

There are many reasons for the immigrant pay gap: They may not have access to networks that can help them land jobs, their qualifications may not be recognised, and they may not speak English.

However, as with the gender pay gap, the researchers tried to account for many of these factors – and again, found that large parts of the pay gaps could not be accounted for simply by differences in characteristics like qualifications or amount of part-time work.

Overall, Pakistani and Bangladeshi people – both men and women – experience the worst pay gaps. Pakistani and Bangladeshi women who are immigrants were the only groups of women who had major negative pay gaps compared to white British women, while Pakistani and Bangladeshi men had among the worst pay gaps of any ethnic background – just under half of Bangladeshi men and about a third of Pakistani men were paid below the Living Wage between 2011 and 2014.

Women born in Britain with a black African background had the largest pay advantage over white British women, earning around 21% more per hour, slightly ahead of Chinese-British women.

Disability

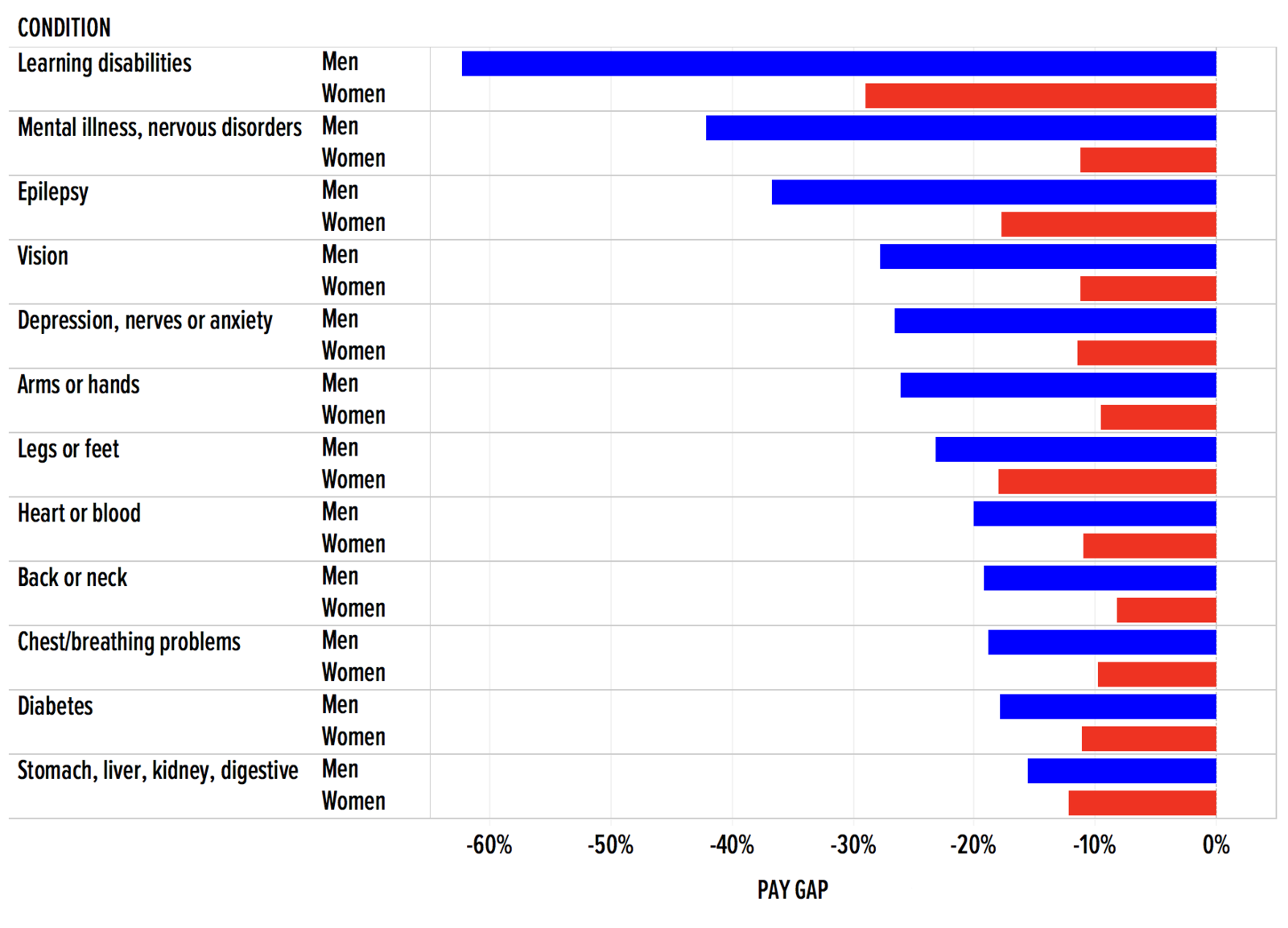

The research found that while there are major pay gaps for disabled people overall, they vary greatly depending on the type of disability – those with mental illness, neurological disorders, and learning difficulties or disabilities have among the worst pay gaps. Men who have depression or anxiety earn almost 30% less, while men with epilepsy have a pay gap of nearly 40%. Men with learning disabilities had a pay gap of over 60%.

Among the reasons for the disability pay gap (in addition to discrimination) are lower education levels for disabled people, and the fact that they are more likely to work part-time. Disabled people are already far less likely to be in employment than their nondisabled counterparts.

As with ethnicity, pay gaps for disabled men (compared to nondisabled men) are worse (13% overall) than for disabled women compared to nondisabled women (7%). While disability increases the pay gap for people from ethnic minorities – a disabled Bangladeshi man has a 56% pay gap compared to a nondisabled white British man – although the study didn't find any suggestion that the disability pay gap itself was worse for any particular ethnic group.