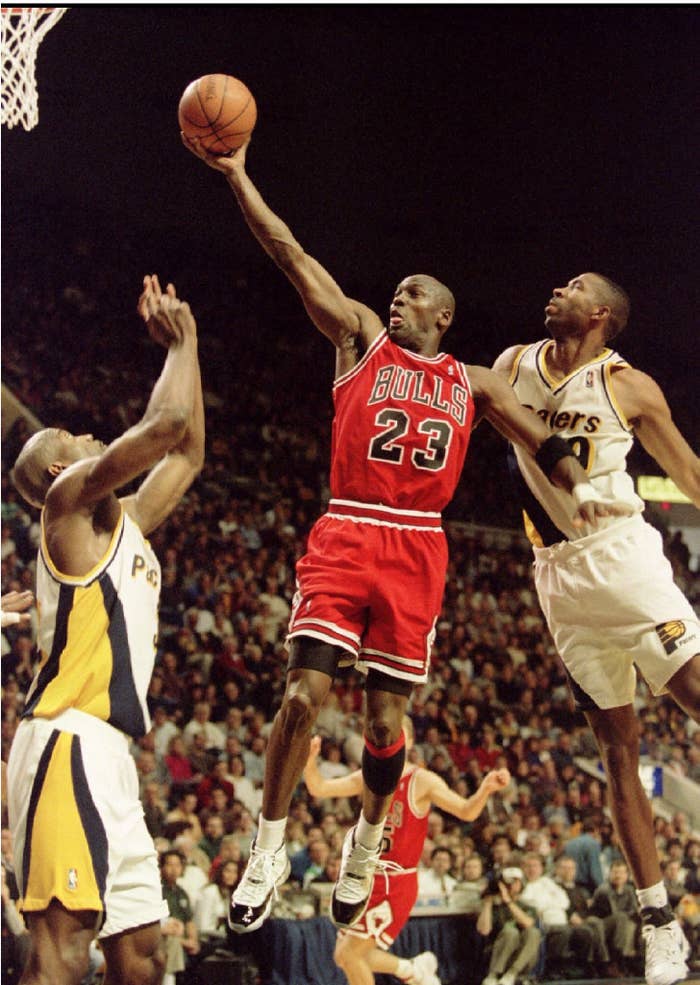

Michael Jordan didn’t make his high school basketball team in 1978. He went on to become the greatest player in the game’s history. This is what he says about failure: “I've missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I've been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

According to a theory that has swept education in the last few years, Jordan has what psychologists call a “growth mindset”. He believes that even if you can’t do something initially, you can improve your abilities, whether they involve basketball or maths or playing the oboe, through hard work. “I can accept failure,” he said. “Everyone fails at something. But I can't accept not trying.”

Psychologists say the growth mindset is contrasted to a “fixed mindset” – the belief that your skills are innate, genetically endowed and fixed. Someone with a fixed mindset, according to the theory, would look at a maths problem they couldn’t do, and think, I can’t do that, I’m not gifted at maths. They might give up. But someone with a growth mindset might apparently think, I just haven’t learnt enough maths to do that; I’ll learn some more and try again. They will keep trying in the face of difficulty – believing they can improve to meet challenges.

These ideas, known as mindset theory, have been described as a “revolution which is reshaping education”. Proponents say you can instil a growth mindset in a child through simple measures – notably, by praising them for how hard they work to achieve something, rather than for what they achieve – with impressive results.

It has garnered an enthusiastic following, with techniques marketed by a variety of training companies. Children in British schools make “mindset” posters to show the difference between the two states of mind, and hundreds of schools in the UK and US offer mindset programmes. NASA looks for, and tries to instil, a growth mindset in its top engineers, saying that fixed-mindset people feel “threatened by the success of others” and “plateau early and achieve less than their full potential”, while growth-mindset people “find inspiration” in others’ success and reach “ever higher levels of achievement”. Google looks for a growth mindset in new hires. The Harvard Business Review offers tips for how companies “can profit from a growth mindset”.

The concept is largely based on the research of Stanford professor Carol Dweck, whose book Mindset has sold over a million copies. A new edition was out on 12 January.

Dweck said in a talk to Google that she has worked with a US baseball team, asking them, for example, what they’d have to change about their approach if they became more successful. Some answered that they'd have to get used to playing in front of larger crowds. But others said they'd have to “take all my skills to a new level”, thus showing the growth mindset, according to Dweck.

She has made some eye-catching claims for the effects of the theory. Her website claims that a fixed mindset caused the Enron scandal, while a growth mindset can encourage cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians. “Almost every truly great athlete – Michael Jordan, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Tiger Woods, Mia Hamm, Pete Sampras – has had a growth mindset,” she believes.

Dweck says that people with a fixed mindset “are so concerned with being and looking talented that they never realise their full potential” and “when faced with setbacks, run away … make excuses, they blame others, they make themselves feel better by looking down on those who have done worse”. By contrast, a growth mindset “fosters a healthier attitude toward practice and learning, a hunger for feedback, a greater ability to deal with setbacks”.

But some statisticians and psychologists are increasingly worried that mindset theory is not all it claims to be. The findings of Dweck’s key study have never been replicated in a published paper, which is noteworthy in so high-profile a work. One scientist told BuzzFeed News that his attempt to reproduce the findings has so far failed. An investigation found several small but revealing errors in the study that may require a correction.

Dweck has been quick to explain and correct the mistakes – earning praise from the scientist who pointed them out – and denies that a failure to replicate her work is an indicator that the findings are shaky.

One of her first and most influential studies on the subject, authored with Claudia Mueller in 1998, claimed to find that teaching a growth mindset made children more likely to take on difficult challenges. One hundred and twenty-eight children took an intelligence test. They were all told that they had scored more than 80%, and that this was a high score. A third of them were then told “You must have worked hard at these problems” - to supposedly instil a growth mindset - another third were told “You must be smart at these problems”, and the rest were left as a control and given no further feedback.

All were then given a choice of further tests to do: either ones described as “problems that are pretty easy, so I’ll do well” or “problems that I’ll learn a lot from, even if I won’t look so smart”. Children who were praised as “smart” overwhelmingly opted for the easy problems; children praised as hard-working overwhelmingly chose the harder ones; the control group was evenly split. Similarly, when children were given another, harder test, those who had been praised as smart reported enjoying the challenging questions less than the children praised as hard-working.

The study has been hugely influential in social psychology – it has been cited by more than 1,200 other papers – and mindset theory has had a profound impact on business hiring practices and educational policy. A blog post on the British government website recommends hiring for growth mindset. Bill Gates has reviewed Dweck’s book in glowing terms. The University of Portsmouth got a £300,000 grant to carry out a mindset study on 6,000 British pupils this year, while educational bodies across Britain – including in Camden, Scotland, and Essex – want teachers to encourage a growth mindset in their children.

But the striking effects in Dweck’s findings have surprised psychologists. Timothy Bates, a professor of psychology at the University of Edinburgh, told BuzzFeed News that the “big effects, monstrous effects” that Dweck has found in the 1998 study and others are “strange – it’s an odd one to me”.

Scott Alexander, the pseudonymous psychiatrist behind the blog Slate Star Codex, described Dweck’s findings as “really weird”, saying “either something is really wrong here, or [the growth mindset intervention] produces the strongest effects in all of psychology”.

He asks: “Is growth mindset the one concept in psychology which throws up gigantic effect sizes … Or did Carol Dweck really, honest-to-goodness, make a pact with the Devil in which she offered her eternal soul in exchange for spectacular study results?”

Recently, other high-profile social psychology findings have come into question. The most prominent is the “power pose”, the idea that adopting assertive poses can make you more willing to take risks and even change your hormone levels. A TED talk on the subject by one of the study’s authors has been viewed 37 million times. But Andrew Gelman, a professor at the Applied Statistics Center at Columbia University and one of the most highly respected statisticians in the field, pointed out last year that the study was riddled with poor statistical practice, and one of its co-authors has recently admitted that she doesn’t think the supposed effects are real. In 2012, Daniel Kahneman, one of the pioneers of social psychology, wrote an open letter to his colleagues warning of a “train wreck” approaching the field if they didn’t improve its statistical practice.

Bates told BuzzFeed News that he has been trying to replicate Dweck’s findings in that key mindset study for several years. “We’re running a third study in China now,” he said. “With 200 12-year-olds. And the results are just null.

“People with a growth mindset don’t cope any better with failure. If we give them the mindset intervention, it doesn’t make them behave better. Kids with the growth mindset aren’t getting better grades, either before or after our intervention study.”

View this video on YouTube

Carol Dweck's TED talk, "The power of believing that you can improve".

Dweck told BuzzFeed News that attempts to replicate can fail because the scientists haven’t created the right conditions. “Not anyone can do a replication,” she said. “We put so much thought into creating an environment; we spend hours and days on each question, on creating a context in which the phenomenon could plausibly emerge.

“Replication is very important, but they have to be genuine replications and thoughtful replications done by skilled people. Very few studies will replicate done by an amateur in a willy-nilly way.”

Nick Brown, a PhD student in psychology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, is sceptical of this: “The question I have is: If your effect is so fragile that it can only be reproduced [under strictly controlled conditions], then why do you think it can be reproduced by schoolteachers?”

Using a statistical method he developed called Granularity-Related Inconsistency of Means or GRIM, Brown has tested whether means (averages) given for data in the 1998 study were mathematically possible.

It works like this: Imagine you have three children, and want to find how many siblings they have, on average. Finding an average, or mean, will always involve adding up the total number of siblings and dividing by the number of children – three. So the answer will always either be a whole number, or will end in .33 (a third) or .67 (two thirds). If there was a study that looked at three children and found they had, on average, 1.25 siblings, it would be wrong – because you can’t get that answer from the mean of three whole numbers.

Brown, who has previously debunked an influential study into “positive psychology”, looked at the 1998 study with the GRIM method. He found that of 50 means quoted in the data, 17 of them were impossible.

Dweck shared the data from the original study with him, and it turned out that the authors hadn't been clear about all of their methods. For example, in some cases they took ambiguous answers as half-scores – a cross marked between 4 and 5 on a study was counted as 4.5. In one part, they dropped a participant but did not report it. There were also several numbers that were entered incorrectly into the report.

Brown told BuzzFeed News that Dweck’s “openness and willingness to address the problems” has been “exemplary”, and that she has done a “thorough job of owning up to the problems” of the paper. She has publicly acknowledged these errors and says she is "considering" writing to the journal to ask them to formally correct the paper.

Brown did, however, point out that Dweck’s work has propelled a huge growth mindset field. Most of the widely cited papers on the subject are by her and her immediate collaborators, he said. “The meta-analyses [studies of studies] are all full of Dweck’s articles,” he said. “I happened to look at this one and I can immediately see lots of things that are wrong with it. What else might not have been analysed correctly?”

Stuart Ritchie, a psychologist at the University of Edinburgh, told BuzzFeed News that another of the foundational studies – a 2007 paper by Dweck, Lisa Blackwell, and Kali Trzesniewski, which has been cited more than 1,500 times – leant heavily on weak evidence. It found that a mindset intervention increased the time teenagers spent trying to solve a maths question. But Ritchie said that one of the central findings didn’t meet the usual scientific definition of “significance”. This is measured by a value called “p” that is usually required to be less than 0.05 for a finding to be considered significant.

“They report the interaction as ‘p [is less than] 0.1’ – so, er, not statistically significant then,” Ritchie said. “But then they just interpret it as if it was significant. I think there’s good reason to be concerned that this isn’t super-solid science.”

Ritchie has also noted a problem with Dweck’s more recent work – a 2016 paper with Kyla Haimovitz in the journal Psychological Science. The study's title suggested that children’s mindsets were more related to their parents’ attitudes to failure than their parents’ attitudes to intelligence – but Ritchie says the difference between the findings was so slight that it can’t be counted as significant. “This is a very, very common statistical error,” he said. “I see it all the time in the literature.” But what is interesting, he claims, is that Psychological Science retracted a paper in 2015, in part for making the same mistake.

“They're using statistical methods that are known to be biased,” Gelman, the Columbia statistics professor, told BuzzFeed News. He has discussed Dweck’s work on his blog and said he thinks “they're using statistical methods that will allow them to find success no matter what,” he said.

Dweck responded to BuzzFeed News’s questions with documents addressing these concerns, which she has put online here, here and here. She said that the non-significant effect in the 2007 paper was "for a follow-up analysis to illuminate the results and we acknowledged in the paper that this effect ought to be replicated with a larger sample." She added: "In the 2016 paper, we can see how the paper's title (What Predicts Children’s Fixed and Growth Intelligence Mind-Sets? Not Their Parents’ Views of Intelligence but Their Parents’ Views of Failure) could have been misleading. The paper itself never claims to compare the effect of parents’ attitudes to intelligence with their attitudes to failure and, most important, none of the key findings rest on this.

"However, in light of the confusion, we are seriously considering changing the title. We are fans of open science and are happy to participate in this process."

Dweck has written several books on mindset and charges $20,000 for speaking appearances, and her “Brainology” mindset programme for schools charges $20 or $50 per student. Her research is funded by Stanford and grants, rather than proceeds from books and talks, so this is not seen as a conflict of interest by journals and does not have to be declared as such when she publishes a study.

She told BuzzFeed News that she doesn't feel that she has a conflict of interest and has “never been motivated by financial gain”.

“I care much more about my credibility and my legacy, my contribution, than about any financial compensation,” she said. She pointed out that she has divested all her interests from the mindset-promoting company Mindset Works, which she co-founded, and has written several articles denouncing the misuse of mindset ideas in schools. “I care greatly about that,” she said. She worries in one article that teachers often “take their existing beliefs and practices” about teaching children to be hard-working and open-minded, and “re-label them ‘growth mindset’”. In contrast, she recommends specific exercises like “sitting down with students who are stuck and saying: ‘Show me what you’ve done – let’s figure out how you’re thinking and what you can try next,’” and “Giving students meaningful problems (rather than rote memorisation of facts and procedures).”

Ultimately, she feels her ideas have not always been practised as intended: “We're spending an incredible amount of time trying to create materials for teachers in how to implement it faithfully and effectively. We've been broken-hearted about some of the misguided ways in which it has been applied.”

Bad statistical practice is rife in science, but especially social psychology, said Brown: “I have the impression that doing statistics properly requires about as much specialised training as you need to fly an aircraft. The majority of scientists have got the equivalent of a driving licence. And so you’ve got scientists out there saying, ‘I’ve got a driving licence, how hard can it be to fly a plane?’ And then clambering into a plane and flying it into a cliff.”

Bates doesn’t think that the mindset hypothesis should be thrown out. He said that there is an uncontroversial reading of the idea – “a very conservative, old-fashioned one: ‘If you don’t work at it you won’t get the results’” – but that, in her TED talks and books, Dweck pushes a more dramatic version, that instilling a growth mindset in children “really works, and you can expect big things from it. She thinks it’s really big, that it’s massive.”

And if it’s not real, it’s a problem, Bates said, because it has become so widespread. “It's affected teaching behaviour massively,” he said.

“If you google it you'll find hundreds of schools around our country, and around the world, where they are giving kids mindset lessons.”