There's a study out that says "light to moderate alcohol consumption" may have "protective" health effects.

Or, in normal human language, a small amount of drinking might be good for you. The study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and led by a researcher at Shandong University, China.

You would be forgiven for thinking you see contradictory headlines about alcohol consumption pretty often. Alcohol is good for you one week and bad for you the next.

I mean, just look at this:

If you do a quick Google search of the Daily Mail site for "red wine cancer", for instance, the top four results include two "red wine causes cancer" stories and two "red wine prevents cancer" stories.

And therefore you might think that the appropriate response to the whole situation is ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Because it kind of looks like no one knows what they're talking about.

But that's not the case. Despite all the back-and-forth, the consensus around the health effects of alcohol has hardly shifted in years.

TL;DR: Heavy drinking is bad for you; what counts as "heavy" is probably less than you think; and light to moderate drinking is probably good for you, although there are statistical reasons why it's hard to be absolutely sure about that, and again what counts as "light" or "moderate" may be rather lighter and more moderate than a lot of people realise.

Let's take a look at this study. It looked at the health records of more than 300,000 adult Americans over eight years, and divided them up into six groups.

The groups were: lifetime abstainers; lifetime infrequent drinkers; former drinkers; and current light, moderate, or heavy drinkers. Then it looked at how likely they were to die during the study for any reason, and specifically of cardiovascular disease or cancer.

It found that heavy drinkers did worse than nondrinkers, but light drinkers did better.

Over the eight years the study ran, about 34,000 of the participants died – roughly 1 in 10. It found that heavy drinkers were about 10% more likely than lifetime abstainers to die for any reason, and about 25% more likely to die of cancer specifically.

But light to moderate drinkers were less likely to die than lifetime abstainers: They had about a 20% reduced risk of dying for any reason, and were about 25% less likely to die of cardiovascular disease specifically.

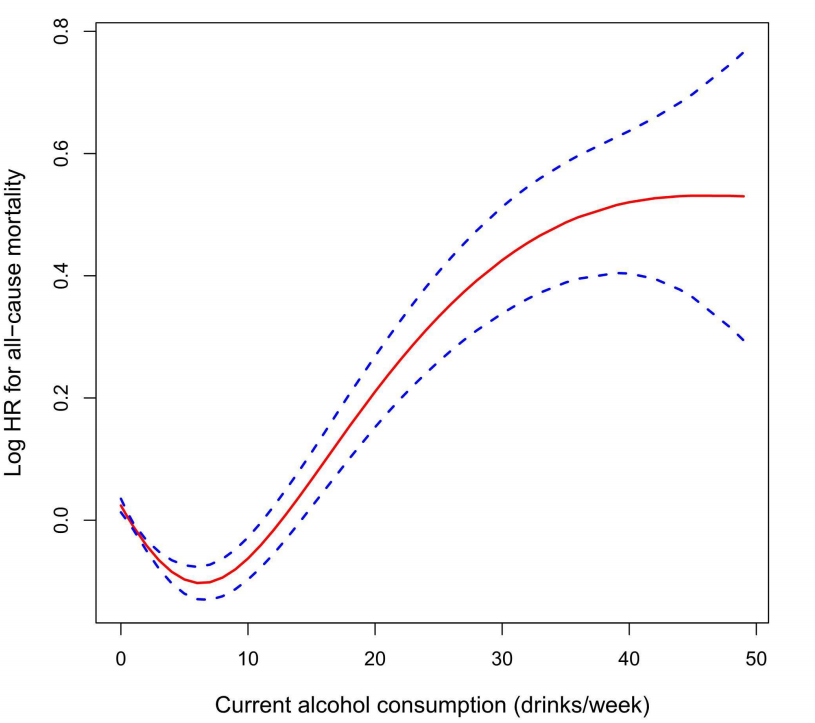

That finding is called a "J-shaped curve". As the dose of alcohol goes up, the likelhood of death in the given period goes down a bit at first, like the bottom of a J, then up.

It's not really very like a J-shape. More of a tick, or a Nike swoosh. But it's too late to do anything about that now.

This is a big study, it seems to be well done, and they've taken steps to try to avoid the problems you get in research like this. But the findings are not new or surprising.

There have been arguments over the J-shaped curve, whether it is "real" or just a product of how the data is collected, going back to at least the 1970s.

An even bigger study than this one, proclaiming similar results, came out in March this year; yet another, back in 2015, looked at fewer people but over a much longer period, and again reported the same sort of finding.

I found those in a couple of minutes' googling on the amazing NHS Choices Behind the Headlines website (which you should absolutely use); no doubt I could find dozens more.

And you probably shouldn't take it to mean "OK, drinking is good for me now". For one thing, although drinking moderately probably has this protective effect, it's still hard to be sure.

The trouble is that these studies usually look at groups of drinkers to see how well they do compared to nondrinkers. But it might be that nondrinkers, on average, are less healthy anyway.

"People who don't drink might have given up because they're ill," David Spiegelhalter, the Winton professor of the public understanding of risk at the University of Cambridge, told BuzzFeed News. That means that they might have been slightly more likely to die as a group anyway, and that's the reason that they look worse than people who drink.

You can try to avoid these problems, but you can never do it perfectly.

Some studies, including this latest one, try to get around it in various ways – this one only looks at lifetime nondrinkers, so the "quit for health reasons" crowd isn't included. But people who've never drunk in their lives are fairly unusual, in Western society, as well. So there may be some other factor that we haven't thought of. "For some unclear reason they may have worse health," Spiegelhalter says.

The thing to do, Spiegelhalter says, is not to look at nondrinkers at all, and just see how the picture changes as you move from very occasional drinking, up through moderate drinking, to heavy drinking. And when you look at that, "it doesn't appear that there's a steadily increasing risk. Once you get above the NHS guidelines of 14 units a week, that's when risk starts taking off. So, at the very least, there's a plateau." He thinks, looking at the evidence overall, that the J-shaped curve probably is real, although he doubts that it's as dramatic as this study suggests.

Even if it is real, it's worth noting what counts as "light" or "moderate" drinking. It's not a lot.

The study defined "light" drinking as less than three alcoholic drinks per week. A "drink" is defined as anything containing 17.5 millilitres of pure alcohol. So two pints of a 5% lager a week, or two large glasses of 12% wine, would put you over the "light drinking" limit.

"Moderate" is defined differently for men and women. For men it's 14 drinks a week, so 245ml of pure alcohol; for women it's 7, so 122.5ml. For men that means a little more than a pint of lager or a large glass of wine a day; for women, half that. And the drinks have to be spread out over several days for the effect to exist, because binge-drinking brings its own risks.

Because the levels are so low, Spiegelhalter thinks "light" and "moderate" are unhelpful terms to use, and that instead we should talk in terms of the risks at specific levels.

So this study confirms what we already knew – that drinking small amounts is unlikely to be harmful, and may even be good for you. But we are talking small amounts.

Spiegelhalter says that it's a vindication for the new, low-risk NHS guidelines, which came out last year and recommended that everyone keeps to 14 units a week – the equivalent of about eight of the "drinks" the study discusses, so roughly in between the moderate levels for men and women.