President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the CIA staunchly advocated for the destruction of videotapes showing detainees being tortured and obtained the legal opinions that were used to justify their destruction, a BuzzFeed News review of records and published accounts shows.

That version of Gina Haspel's role in destroying the tapes contradicts the narrative being pressed by CIA officials that Haspel was only following orders when she helped engineer the tapes’ destruction and that she has served the agency well for 33 years, almost all as a clandestine officer.

The narrative is intended to help build support for Haspel, who in the early 2000s was chief of staff to Jose Rodriguez when he ran the CIA’s National Clandestine Service and authorized the tapes’ destruction. She's now the CIA's deputy director.

What Haspel did in the lead-up to that destruction is likely to be a major point of contention as the Senate considers her nomination. At least four senators, including Republican Rand Paul, have said they will oppose her confirmation because of her role with the tapes and in the CIA’s so-called enhanced interrogation program.

“The destruction is a high concern for me,” Sen. Angus King told BuzzFeed News. King, a member of the Senate intelligence committee, said Haspel’s involvement with the tapes concerns him more than her role in harsh interrogations because, while harsh interrogations had been approved, the destruction of the tapes went against senior officials’ wishes.

Those officials included the White House counsel to President George W. Bush, Alberto Gonzales; his successor, Harriet Miers; Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff David Addington; Director of National Intelligence John Negroponte, CIA Director Porter Goss and CIA acting general counsel John Rizzo — whose objections, Rodriguez wrote in a memoir, he was well aware of.

Haspel and Rodriguez “were the staunchest advocates inside the [CIA] building for destroying the tapes,” Rizzo wrote in his 2014 memoir, Company Man: Thirty Years of Controversy and Crisis in the CIA. “On the edges of meetings on other subjects, in the hallways, they would raise the subject almost every week.”

Rizzo’s book does not name Haspel but identifies her as Rodriguez’s chief of staff. At the time, her chief of staff job was classified.

When Gonzales became attorney general in early 2005, Haspel and Rodriguez “began lobbying me to revisit the issue with the new White House counsel, Harriet Miers, in the hope that she might not have the same deep reservations that Gonzales and the other White House lawyers expressed to Scott Muller in 2004,” Rizzo wrote.

Muller was CIA general counsel — the agency’s top lawyer — from 2002 to 2004. At a White House meeting on May 11, 2004, he was “told by Addington and Gonzales not to destroy the tapes,” according to a CIA timeline released to the American Civil Liberties Union in response to Freedom of Information Act requests submitted in 2003 and 2004.

Rizzo declined to be interviewed for this story as did Gonzales, Miers, Addington, Muller, and Negroponte. The CIA declined to comment.

Haspel has made no public comment since Trump announced March 13 that she was his pick to succeed current CIA director Mike Pompeo, whom Trump intends to name secretary of state. Haspel was photographed by a BuzzFeed News reporter last week leaving the Senate Intelligence Committee offices.

Gina Haspel, nominee to become the next CIA director, left the Senate Intelligence Committee's offices a few minutes ago. https://t.co/UJzEg7jgC7

The crucial events concerning Haspel occurred over a 10-day span in late 2005 while Congress was considering creating an independent commission to investigate the CIA’s treatment of detainees. At the time, few outside the CIA knew the tapes existed.

Rizzo, the CIA general counsel, sounded the alarm in an Oct. 31, 2005, email saying the idea “seems to be gaining some traction, which obviously would serve to surface the tapes’ existence.”

Rodriguez and Haspel moved immediately to destroy the tapes so they did not get out of the CIA’s control.

But instead of consulting with Rizzo, Haspel met with lower-ranking attorneys in the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, which Rodriguez had once headed, and asked if they believed Rodriguez had the authority to order the tapes’ destruction, according to Rodriguez’s 2012 memoir, Hard Measures: How Aggressive CIA Actions After 9/11 Saved American Lives.

Rodriguez says in his memoir that he was frustrated at delays in approving the tapes’ destruction and the seemingly endless reviews by the White House and National Security Council. “If I had waited for them to give me the go-ahead, I would still be waiting,” Rodriguez wrote.

Haspel then wrote a memo for Rodriguez to authorize the destruction, which Rodriguez sent to the CIA station chief in Thailand, where the tapes were being kept, according to Rodriguez’s memoir.

On Nov. 9, 2005, the 92 tapes were destroyed in an industrial shredder.

Inside the CIA, Rodriguez was hailed for having the tapes destroyed. “He’ll be forever remembered at the agency as a hero for it,” former CIA director Michael Hayden wrote in his 2016 memoir, Playing to the Edge.

A.B. Krongard, who managed the CIA’s day-to-day operations as executive director until his retirement in 2004, told BuzzFeed News that he is “very sympathetic” to Haspel and called her “just a professional doing her job.”

James Mitchell, a psychologist who helped the CIA develop the enhanced interrogation program, told BuzzFeed News that Rodriguez “did the right thing.”

But in Congress and upper levels of the CIA and the Bush administration, officials were outraged, according to interviews and declassified CIA records. Some had made it known they wanted to preserve the tapes, in part because they might be needed in court cases that were active.

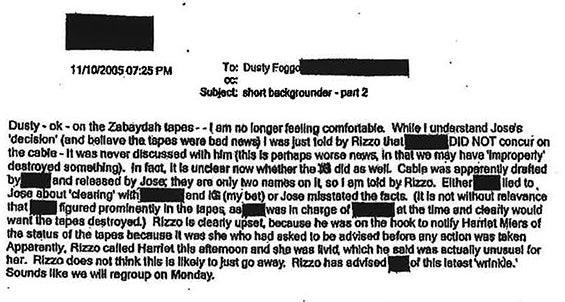

On the day after the tapes were destroyed, a senior CIA official wrote a panicked email to the agency’s executive director saying that the action “was never discussed with” Rizzo, according to a copy of the email, in which the author’s name is blacked out. The ACLU obtained the email through its public-records requests.

“We may have ‘improperly’ destroyed something,” the official wrote to then–executive director Kyle Foggo, the third-highest ranking CIA official. “Rizzo is clearly upset.”

The email adds that when Rizzo told Miers that day about the destruction, “she was livid, which he said was actually unusual for her. Rizzo does not think this is likely to just go away.”

Rizzo said in his book that he had approved having the Counterterrorism Center lawyers work on a memo to get the tapes destroyed. But, he wrote, he expected their draft would only “‘tee up’ the issue for [CIA] headquarters” and be used as a starting point for discussions with the White House about destroying the tapes.

Jane Harman, who’d been briefed on the CIA’s desire to destroy the tapes in 2003 when she was the top Democrat on the House intelligence committee, also had told the agency not to destroy the tapes. Now the head of the Wilson Center in Washington, she still looks back on their destruction with dismay, saying it prevented Congress from viewing them to determine how detainees were treated and if the harsh interrogation techniques had yielded helpful intelligence.

“They were deliberately destroyed to destroy part of the record,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I find that completely unacceptable. Who knows what really happened there [in the interrogations]? We would know if we had the tapes.”

Although the Justice Department had approved the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” program, the CIA’s inspector general found in 2004 after viewing the tapes that CIA officers had used harsher techniques than had been approved.

Sen. John McCain, Congress’s leading opponent of torture, asked Haspel in a March 23 letter whether she had any role in destroying the tapes or advocated for their destruction, and if so, why. Haspel has not responded to McCain's letter.

Rizzo, the former CIA lawyer, said in a recent interview on National Public Radio that the tapes’ destruction is “a legitimate area of inquiry for the [Senate intelligence] committee.”

Both Rodriguez and Hayden have said the tapes were destroyed to protect the identities of CIA officers whose faces were visible. “The tapes posed a serious security risk,” Hayden said in a statement in December 2007 when news of the destruction was first published. A leak would expose CIA officers “and their families to retaliation from al-Qaida and its sympathizers.”

Rodriguez said in his book that he was “just getting rid of some ugly visuals that could put the lives of my people at risk.”

But in a 2017 court deposition in a now-settled lawsuit against the two psychologists who helped design the enhanced-interrogation program, Rodriguez said that a “secondary reason” for destroying the tapes was that their release “would make the CIA look bad, and it would actually, in my view, you know, destroy the clandestine service.”

Asked if he could have blurred the CIA officers’ faces instead of destroying the tapes, Rodriguez said, “I was not about to take that chance.”

After the CIA acknowledged in late 2007 that it had destroyed the tapes, the Justice Department launched a criminal investigation. No charges were brought.

An internal CIA investigation also cleared Haspel but resulted in a reprimand against Rodriguez, according to a book and column by Michael Morell, who investigated the tapes’ destruction when he was CIA deputy director.

“The written record made it clear that he’d known that his bosses, not to mention the White House counsel, did not want the tapes destroyed,” Morell wrote of Rodriguez in his 2015 book The Great War of Our Time.

As for Haspel, she acted “at the request of her direct supervisor and believing that it was lawful to do so,” Morell wrote in a 2017 column.

CORRECTION

Kyle Foggo's name was misspelled in a previous version of this post.