On the night of July 2, 2015, Tommie Woodward was doing what Tommie did on Thursday nights — shooting pool, playing shuffleboard, drinking beer, having a good time at Burkart’s Marina, a beer and burger joint in Orange, Texas. Sometime around 2 a.m. he decided to go for a swim in the murky waters of Adams Bayou.

Michelle Wright, the bartender on duty, became concerned upon hearing Tommie’s plans. A few weeks earlier, the bar’s owner, Allen Burkart, spotted an exceptionally large alligator patrolling the bayou. He immediately erected a “No Swimming” sign, which was disregarded. The people of Orange frequently swam with the reptiles, and even nicknamed two of them Cheeto and Marshmallow. Wright pleaded with Tommie, but he was stubborn, never backed down from anyone or anything. He was going swimming. Wright returned to her bartending duties.

Tommie removed his shirt and billfold and, joined by his companion Victoria LeBlanc, tiptoed toward the water. At this point LeBlanc saw a big gator — maybe the same animal Burkart had encountered — emerge from beneath the dock. She alerted Tommie to its presence, who shouted back, “Fuck that gator!” and plunged into the bayou.

Tommie was near a small island across the swamp when the gator got his arm. When LeBlanc jumped into the water to save him, he yelled for her to return to land. She obliged, then frantically ran inside for help. After dialing 911, Wright grabbed a flashlight, killed the lights to reduce the glare, and scanned the water for him. After five minutes or so — she’s unsure — Wright found him facedown near the pier. The gator quickly pulled Tommie under again. He resurfaced about 20 yards downstream, before disappearing into the darkness.

Two hours later Tommie’s body was found with the left arm missing from the elbow down. His cause of death was drowning.

Tommie Woodward was the first person to die from an alligator attack in Texas since 1836. Shortly after the start of the Runaway Scrape, the mass evacuation of Texans fleeing Santa Anna’s army during the Texas Revolution, an alligator killed a man identified as Mr. King in a bayou near the present-day Harris County border. Mr. King was leading his horses across water when an alligator thumped him with its tail and dragged him under. Luckily for Mr. King — and his friends and family — his death occurred before the advent of television and social media.

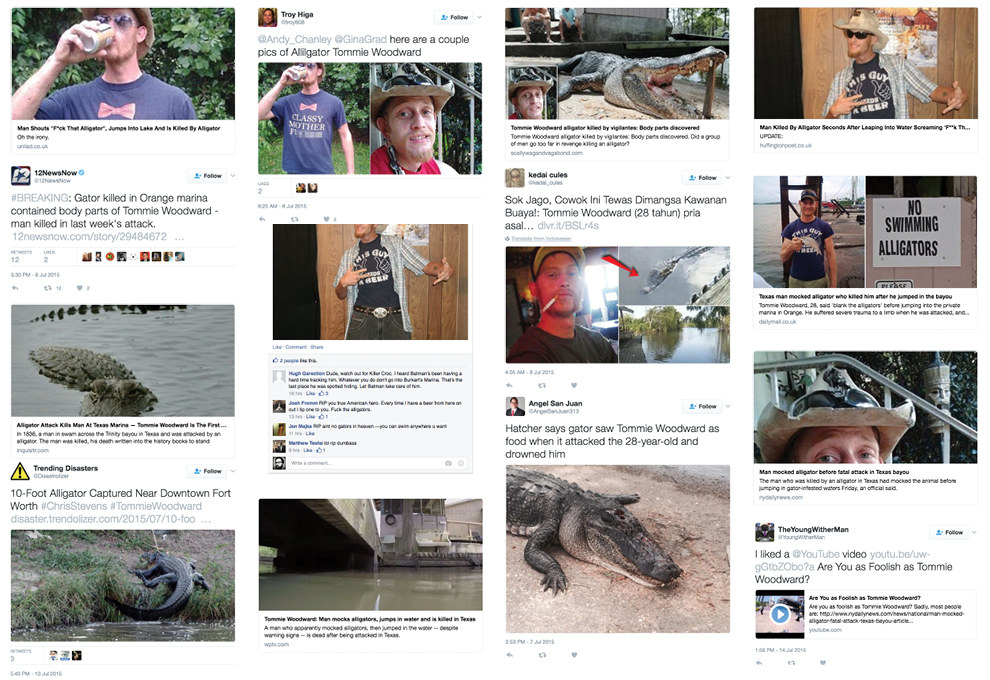

News of Tommie Woodward’s death went viral with articles on, among other places, BuzzFeed, the Daily Mail, Fox News, and Gawker; the Associated Press picked up the story; it led the local TV news, of course. The local Beaumont Enterprise published a cautionary op-ed. The comment sections were busy and typically unsympathetic. The particulars — an animal attack, his famous last words, according to the police report — provided irresistible content.

“I was severely pissed off at a lot of people that I’ve never met before. I was mad at everybody.”

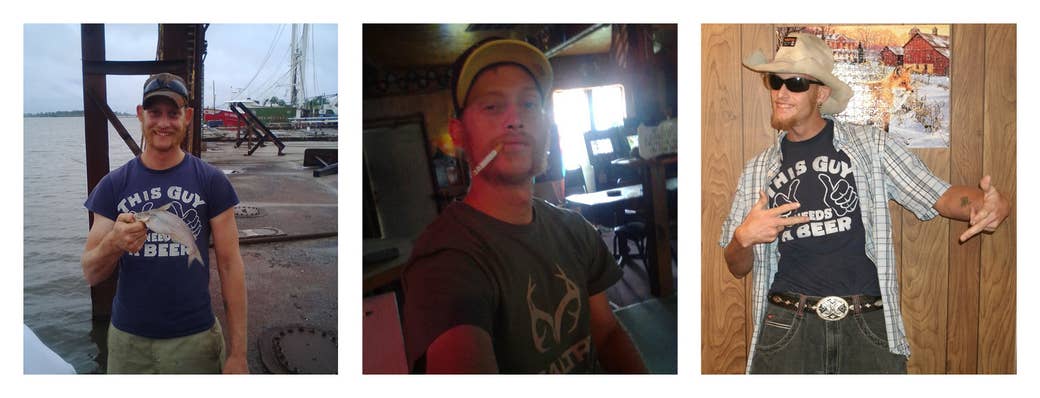

Some outlets used an image from Tommie’s Facebook page of him chugging a Miller High Life while wearing a T-shirt that reads “Classy Motherfucker”; a news anchor for KFDM, the CBS affiliate in nearby Beaumont, breathlessly noted “the hundreds and thousands of pageviews and hundreds of comments” that the story generated on its website. Another circulated photo portrayed Tommie as the epitome of dudedom: grungy reddish-blonde chin strap beard, middle finger up, wearing a goofy cowboy hat, wraparound Guy Fieri shades, and a “This Guy Needs a Beer” shirt. On Facebook, strangers littered Tommie's wall with comments like “lol rip dumbass” and “What. A. Dumb. Fuck.” A controversial hunt for the killer gator ensued, which only compounded the attention.

Tommie’s friends and family refuse to allow his final actions define the 28 years that preceded it. He loved Van Halen, Marilyn Monroe, and Ken Griffey Jr. He was good with his hands. He enjoyed assembling computers, building sandcastles with his nephew, fishing, swimming, camping, and grilling. He had an adoring big sister, a mom, a best friend, and an identical twin brother, Brian, all left to wrestle not just with grief over a freak tragedy, but also the aftermath of public humiliation. “I was severely pissed off at a lot of people that I’ve never met before,” his sister, Tabatha, says. “I was mad at everybody.”

But no one was affected like Brian was.

Within minutes of meeting last December in Beaumont, Brian Woodward ditches me inside a popular seafood restaurant and retreats to the parking lot. Moments later I find him standing beside his 1999 Dodge Ram 1500. “Come on,” he says, climbing into the driver’s seat. He blows into a Breathalyzer to start the car. “I don’t like people,” he tells me. “I walk in somewhere packed with people I don’t know, fuck you, I’m gone.” We drive to a Chili’s in Orange, the easternmost city in the state, where he now lives.

The area in Southeast Texas between Orange, Beaumont, and Port Arthur is referred to as the “Golden Triangle.” In 1901, a gusher in the Spindletop oil field in Beaumont blew for nine days, spouting an estimated 100,000 barrels of oil per day and transforming the region’s economy. The Texas oil boom was on. A century later, refineries and chemical plants are still big employers in the area.

Brian worked at the shipyards upon moving into town. It was arduous labor, just as he liked it. A vessel needing repairs would be dry-docked. From there, Brian and his team, a tight, rowdy crew of ballbusters, would do anything from change rudders to remove the motor. He enjoyed going to work each morning, but soon realized that promotions at the shipyards were unattainable. “The only way you can move up,” he says, “is if someone dies.”

We talk while he drives. “I can go to that shipyard now, ask for a job, and have it. You can’t find too many people that can outwork me. Pound for pound, you can’t beat my little ass. Tommie was the same way. He worked real hard. Most people nowadays, they’re not — they just don’t. Tommie lived with me and worked with me at the shipyards. Then I had to get out. I wasn’t making enough money." Brian worked on tugboats offshore for a while but didn't like being away from home. "I do AC work now. I install air conditioners in people’s homes — million-dollar homes, piece-of-shit homes.”

Brian weaves between lanes on Interstate 10 hugging the 80 mph speed limit; his toolbox clangs violently around the backseat. The Breathalyzer beeps, and he blows into the black plastic tube. “Chicken Fried” by the Zac Brown Band plays on the radio. “Why are you grabbing the ‘Oh shit’ handle?” he says after noticing that I’m clutching the passenger side roof handle. “Are you scared?”

Once at Chili’s, Brian orders a 10-ounce sirloin cooked rare. “If they sear it on each side and serve it to me bloody as hell,” he says, “I’d be happy with it.” He takes pride in having eaten things a lot of people wouldn't think to eat, especially during lean times.

“You’ve ever eaten cat? It’s not bad,” he says. For a few months in high school, Tommie and Brian lived in a tent on the banks of the Meramec River. Food was scarce. “The cat kept hanging around — fat motherfucker. I said, ‘I was hungry, so I’m gonna go get it.’ It was more of a vendetta than anything because he kept shitting and pissing everywhere. So I set up a snare to get him. I got him, skinned him like a rabbit — put a stick up his ass all the way through his mouth and then put him over a fire.” How did it taste? “Oily, man. Oily.”

He’s an active storyteller with a McConaughey-esque twang whose eyes gleam when he gets to the good parts. His nickname is Cowboy. Like Tommie, Brian is 5 feet, 10 inches tall, wiry, no more than 150 pounds after Thanksgiving dinner, and wears his long reddish-blonde hair in a monastic ponytail like a Greek priest. The only physical difference between the twins is the webbed toes on Brian’s left foot and a scar outside Brian’s left eye that runs behind his ear, the result of a January 2014 motorcycle accident; the discoloration around the wound makes it look like a tattoo. Brian suffered a fractured skull, broken femur, and shattered pelvis, and was placed in a weeklong medically induced coma following the crash, which also left him with memory problems. “That wreck fucked me up pretty good,” he says. “Tommie helped me. Moral support.” He chuckles quietly to himself.

The Woodward twins were born on July 20, 1986, healthy, on their due date. Their mother, Kelley Creamer-Shibles, stayed home with the twins and Tabatha, one year, one month, and one day older than her brothers, while her husband Tom worked the assembly line at Chrysler. But the couple split when the twins were 3. An acrimonious divorce and custody battle followed.

As teenagers living in Pacific, a small city 30 miles southwest of St. Louis, the twins' divergent personalities manifested: Tommie was the prankster, a social butterfly who made conversation with strangers; Brian was more reserved, sincere. For both, high school was an afterthought, and they dropped out after four years to work fast-food jobs.

“I never would have imagined Tommie going that way. An alligator. That’s just weird.”

Tommie’s peripatetic journey began when he abruptly joined a carnival, a perfect match for him, says his mom. “You know how when you go into a carnival, the people running the games are slick talkers? He was the same way. He could talk you into anything.”

After returning to Pacific, Tommie moved to Arkansas to remodel Sonic Drive-In restaurants with his dad. Work was sporadic, creating tension between father and son. His best friend back home, Jimmy Matthews, would visit, but, Matthews says, the lack of employment tormented Tommie. It soon reached a breaking point.

One day, Brian, now settled in Texas, arrived for a surprise visit. “He was going to live with a friend in the woods. I said, ‘Come with me to Texas. I got a place where you could stay. I got a job for you, too.’”

Tommie lived with Brian, and Brian’s wife and son, for four years, and when he finally left, he moved into a house six blocks away. When Brian would visit, which was often, they’d start a fire in the backyard, throw horseshoes, and drink beer. Splitting three cases was an average night.

“Three o’clock in the morning it was nothing to get a call from Tommie because he was missing me,” says Creamer-Shibles. “He’s like, ‘Mom, I love you.’ ‘Okay Tommie, I know you’re drinking. What’s up?’ ‘Nothing, I’m just calling to say hi.’ I would talk to him until he [went to sleep]. I guess it was that sense of security.” Tommie had “Mom” tattooed on his bicep when he was a teenager.

The twins were regulars at Burkart’s Marina. “It was more of a family,” Michelle Wright recalls. “Everybody had each other’s backs.” Tommie had multiple roles within the clan. Depending on how much he drank, he could be the big brother or little brother. Sometimes he was the bar’s flirt, sometimes the billiards hustler. He loved to dance. He loved to make everyone smile. He also loved to swim in the waters off Burkart’s Marina, no matter the season or time of day.

“I never would have imagined Tommie going that way,” Creamer-Shibles says. “For some reason, I always thought it was going to be some stupid car accident, not an alligator attack. That was the furthest thing from my mind. An alligator. That’s just weird.”

It was 2:34 a.m. at the bayou when Michelle Wright dialed 911. Within minutes, fire and ambulance were dispatched. Orange Police Department arrived at 2:39 a.m. Game wardens from the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department were contacted at 2:42 a.m. with instructions to get a boat into the water.

Once on the scene, the Orange PD handled the investigation as if it were any animal attack. A statement was collected from Wright. LeBlanc, who initially fled Burkart’s Marina, was interviewed once found down the road. It then became clear that Parks & Wildlife would not be conducting a search and rescue mission, but search and recovery.

Warden Clint Caywood and Deputy Jason Guidroz found Tommie's body floating up against a bank next to a tree, approximately 200 yards down the bayou from Burkart’s. After the fire department retrieved the body, it was placed in a body bag and brought back to land where the justice of the peace declared Tommie deceased and prepared the death certificate.

The game wardens still had work to do: Locate the alligator. Usually, game wardens set a line or traps and shoot the alligator once it’s caught. But lines take time to assemble. To expedite things, game wardens were instructed to hunt solely with their firearms. They didn’t find the gator on Friday or on Saturday or Sunday. By then, there were more boats in the water. “This is East Texas — there are a lot of country boys down here,” says Capt. Robert Enmon of Orange PD. “I believed that someone was going to find that alligator and kill it.”

One afternoon in June 2015, Kent Robnett, a 33-year-old construction superintendent from Orange, was returning home from Walmart when his dad called and told Kent to hurry into his kitchen. The kitchen overlooked Adams Bayou. Robnett dropped his groceries, ran, and gazed out the window. And there it was, a big gator tooling down the middle of the bayou.

Robnett was stunned. Having grown up on the swamp, he deemed himself an alligator expert of sorts. He knew that big gators didn’t get that big by being stupid. He also knew that swimming down a populated bayou in the late-afternoon sun were the actions of a stupid gator; gators that size hug the banks, avoiding the main cuts, avoiding humans. From his kitchen, Robnett could see that the gator’s face was littered with scars. Something, he thought, wasn’t right with that animal. As he watched the gator heading south, he thought of his children — a 14-year-old girl, 3-year-old girl, and 1-year-old boy — all of whom frolicked in Adams Bayou. Tommie Woodward died in those waters a few weeks later.

“I took it upon myself when I walked out of that bar. I knew I could get that gator.”

Robnett heard the sirens during the wee hours of July 3 and learned in the morning that Tommie, an acquaintance of his from Burkart’s Marina, was the victim. Like many locals, Robnett went to the bar later that evening. Coincidentally, he sat near Tommie’s friends and family. He eavesdropped on their conversation — and what he gathered was that they wanted that gator gone. “I took it upon myself when I walked out of that bar,” Robnett says. “I knew I could get that gator.” He stayed up all night rigging four lines using frozen chicken as bait.

Robnett, who comes from a long line of hunters and trappers out of Southwest Louisiana, killed his first gator at age 10. “I love gators,” he says. “I have a lot of respect for those animals. I cared for them. We would never disrespect anything we harvest. But that gator had to go. He killed a man.”

Over the weekend Robnett sat on his back porch watching the game wardens hunt near where Tommie's body was found. He questioned their tactics. The gator, Robnett said, wouldn’t return for seconds. He gave the game wardens 72 hours to find it.

When Robnett ran his lines on Monday morning, he found a giant gator hooked in the first location he checked. The gator had worn that bank out to mud trying to escape. Not a tree, bush, or limb remained within a 20-foot circumference. Robnett looked closer. He recognized the gator. The scars gave him away. “When I looked right in his eyes and he looked in my eyes, a chill come over me,” he says. “I said, ‘Man, you motherfucker.’ His eyes were a mixture of tired and evil and all kinds of shit. I knew it was him. I had no doubt. I’m not one to go out and take the lord’s creatures, but I had no regrets or remorse at all in taking his life right there in that moment.”

Robnett aimed his Glock .40-caliber pistol toward the gator’s head, shooting it at point-blank range. Once the hollow-point tungsten steel bullet pierced its skin, the gator thrashed with enough force to almost knock Robnett from his boat. Robnett then lit a cigarette and watched him bleed out. But the gator, Robnett says, “came back to life with a vengeance.” He shot it again. “That second time, I domed him twice,” Robnett says. “You don’t do that because the second shot will be off. You also don’t do that out of respect for the animal.” In all, Robnett put seven rounds into the gator.

He went home, made a sandwich, and then called a friend to help load the gator into his boat. Robnett felt justified in his actions. “Do you know that show with Nicolas Cage, Treasure Hunt or National Treasure?" he asks. "You know that part where he quotes, not the Declaration of Independence, but he says, ‘People know that something is wrong and they have the ability to do something about it they are obligated to?’ Look it up on your computer.”

I read the Nicolas Cage quote back to him. “If there’s something wrong, those who have the ability to take action have the responsibility to take action.”

“Yes, that’s exactly right,” Robnett says. “That’s what I did, man.” What he had also done was breathe new life into the tale of Tommie Woodward and the man-eating gator. Media attention had waned since Friday morning when the body was found. But, with his actions, Robnett provided a twist in the proceedings, fresh content for both the local news and the peanut gallery on social media. He also, inadvertently, entered the spotlight.

Illegally killing an alligator is a class C misdemeanor, the equivalent of a parking ticket, and punishable by a fine up to $500. So as soon as he unloaded the gator near Burkart’s Marina, Robnett anonymously reported it to game wardens. Jake Daniels, a photographer from the Beaumont Enterprise, saw on Twitter that someone had shot the gator. Once he arrived at Burkart's Marina, he tweeted pictures of the bloody 11-foot beast. A crowd, eventually ballooning to more than 50 people, soon gathered. “It felt like a hunter’s atmosphere,” Daniels says. “It was like, ‘We got done what needed to get done.'”

Daniels’ photographs chronicled the scene: A man drinking a Miller Lite held open the gator’s jaws; a piece of wood propped open its mouth; another man sat on it. Selfies were snapped. Some folks even removed the gator’s teeth. As more news vans appeared, a man calling himself “Bear” gave interviews taking credit for the killing.

The next part of the investigation was determining if this was the gator that killed Tommie Woodward. When game wardens finally arrived, they were joined by Harlan “Bigfoot” Hatcher, a licensed nuisance-control hunter, and the star of Swamp People, Seasons 4 and 5. "I just skinned the gator and opened him up,” he says in his thick Cajun accent. “I’m not no forensic coronary [sic] who do all that stuff. I’m a gator hunter, man.” Bigfoot and the game wardens then examined the contents of the gator’s stomach. After finding skin, nails, and fingers, they decided they had their culprit.

Game hunters are allowed to sell the meat and skin for profit, but, in this case, the meat had gone bad, and Bigfoot refused to “sell nothing off someone’s misfortune.” He scooped and bleached the gator’s skull before giving it to the game wardens. He tanned the hide, which he keeps in storage.

The only question left for the game wardens was whether to charge Bear with a misdemeanor — except, as you know, there was one problem: He wasn’t the killer. “I just thought I’d throw my name out there,” he told ABC 13. Robnett came forward two days after shooting the gator. He wasn’t prepared for the fallout.

Robnett faced intense criticism from animal rights activists, and even claims that he was driven off Facebook. “There was some mean shit said,” he says. “At night I would stay up in the living room with my gun. People were coming by late at night throwing rocks at my house and shit.” But he had supporters, and an anti-gator contingent planned a benefit barbecue at Burkart’s in the event Robnett was fined.

The decision went up the chain of command to supervisors in Austin, who ultimately ruled to give Robnett a written warning. “I think this was a twofold deal,” says Capt. Rod Ousley of Texas Parks & Wildlife. “One: It was a fatality. Two: The individual who killed the alligator got the right one. If he would’ve killed three or four alligators, it would’ve been a different story. He got lucky. He got the right one.”

Brian Woodward was “happy as hell” when he learned Robnett got the gator that killed his brother. “I felt some kind of justice,” he says.

Brian is giving me a quick tour of Orange, Texas, population 18,500, home of the Stark Museum of Art, and the state champion West Orange Stark Mustangs football team. We ride past the drab civic necessities — county jail, municipal court, firehouse, AutoZone — before arriving at a one-level home on Rhode Island Street with junk strewn about the front yard. This was Tommie’s house. “I don’t know who lives here now. Don’t know, don’t care,” Brian says, peering out of his car. “They’ve trashed it. We kept it immaculate clean.”

Brian lives a few blocks away on Texas Avenue. He wants me to see Tommie’s old possessions. “This is me,” he says pulling into his front yard. He’s renting while renovating the house he bought in nearby West Orange. “I spend a lot of time in Home Depot,” he jokes. A Lab mix named Princess, and Neenews, a Pomeranian mix, scamper near “Old Smokey,” Brian’s barbecue pit.

“It may seem weird for me to hang on to every little piece of him for me to remember, but I do.”

We walk through his kitchen, and into Brian’s room. In the corner stands a portrait of Tommie that their mom commissioned following his death. Brian picks it up, holds it at eye level, staring at the familiar face — his own face. “I sure do miss him,” he sighs. “He was a good guy.” He places it aside and begins rifling through the boxes stocked beneath.

One by one, Brian unpacks his brother’s collectibles: Coors glasses, a Dodge hood ornament, a Ken Griffey Jr. baseball card, an old flashlight, a $1 coin crushed on the train tracks, a chunk of the flammable metal tungsten — “throw that in a fire and you’ll have one hell of a fucking fire” — a Skoal canister filled with wheat pennies, a baseball, Tommie’s toolbox, a roach clip, keys from the carnival, a box of chocolates with DFT (Don’t Fucking Touch) written on it, ChapStick, a handkerchief their father made when he was in jail, purple Crown Royal bags, and some old bottles. “It may seem weird for me to hang on to every little piece of him for me to remember, but I do.”

He then puts everything back in the exact order that he unpacked it. I notice that he’s wearing Tommie’s work shirt. “Yes sir, it brings me good luck,” Brian says. He looks to his chest where his brother’s name is inscribed, and strides toward the door. “Let’s go visit the place where he passed.”

Burkart’s Marina closed in September 2016, less than a week before owner Allen Burkart died at the age of 84. A Korean War vet, Burkart was born and raised in Orange where he worked for his father’s plumbing business before starting a moving company. According to his obituary, “his lifelong dream was to have a marina on Adams Bayou.”

As a teetotaler, Burkart preferred that his namesake was not called a bar. So, after Hurricane Ike destroyed his business in 2008, he added shuffleboard tables and games, remaking it into a more family-friendly establishment. The mascot for the bar’s Facebook page was a cartoon alligator holding a beer, and wearing shades, an open shirt, cargo shorts, sandals, and a beaded necklace.

The old man took Tommie’s death hard. “He was very emotional over it,” says Burkart’s granddaughter Angela Hoffpauir Cockerham. “My grandfather was embarrassed that it happened at his place of business. He also felt liable because it was his property.” (According to Texas DRAM laws, a person suing a bar must prove that they were a danger to themselves or others when sold alcohol. Brian says he would never sue. “That was like my family.”)

On this late afternoon, a man stops us as we attempt to park on the property. “I don’t care who you are, motherfucker,” Brian mutters before exiting his car. He slams the door and turns on the charm. “How ya doing?” After a short conversation, Brian motions that we can enter the premises.

We march down a ramp, past the “No Fishing” and “No Swimming Alligators” signs, and into the deserted bar. The view from the wooden picnic benches overlooking the bayou is breathtaking, a wild beauty from another world. Branches from bald cypress trees hang perilously overhead as the dimming sun gently reflects off the water. On a small island across the bayou, a majestic bird — an egret or osprey — swoops into the flat, boggy marshland hunting for prey.

“I spent a many of years in this bar,” Brian says. “I started drinking here before I was 21.” He looks over the water, both hands deep in his pants pockets, and tells me about the night his brother died.

Around 3 a.m. Victoria LeBlanc, soaking wet, agitated, apologizing profusely, knocked on Brian’s door. She told him that Tommie was missing. Finally, she admitted that he drowned. When Brian arrived at Burkart’s less than five minutes later, he didn’t get the information he was looking for. So he returned home, loaded a small boat into his car, and went looking for Tommie. He says that he found his brother’s body. “They wouldn’t let me bring him out of the water,” he says, his voice cracking. “They wanted me to leave him there, and I did.”

Texas Parks & Wildlife game warden Clint Caywood denies Brian’s claim. “His brother was out there on a boat, but, no, he didn’t find him. Me and one of the Orange County sheriff deputies found him,” he tells me. “We had to keep his brother away from him.”

Another way Brian’s story diverges from the official account regards Victoria LeBlanc. He tells me that LeBlanc and his brother dove into the water simultaneously, and that she retreated to land after the alligator’s tail brushed her. According to LeBlanc’s statement, she didn’t jump in until after the attack commenced.

Looking for answers, we go to Michelle Wright’s house. Brian is silent for most of the ride into Bridge City, the next town west. We drive down a long flat road lined with lush greenery. With no radio or conversation, the Dodge’s engine thrums loudly. Twenty minutes later we are in Wright’s kitchen, where fresh-baked chocolate cookies cool on the table.

“I still smoke in here?” Brian asks.

“You could never smoke in here, not with him,” she says, pointing to her adult son, who’s sitting on the couch, eating ramen noodles and watching X-Men Origins: Wolverine. “He has asthma.” Brian slips the unlit Pall Mall into his pack.

“Every time I think about it I want to cry,” Wright says. “I was wondering how I was going to do seeing you. I don’t see you that often anymore. You know, I once had a 15-minute conversation with your brother thinking it was you.”

“A lot of people have done that,” Brian says, smirking.

Wright says that on the night of the alligator attack she didn’t sleep until 7:30 a.m. Every time she closed her eyes she saw Tommie pulled under. The following days and weeks remained difficult, especially at work. It was months, she says, before she could enter the water. And then there were the trolls, who, recognizing her from the local news, bombarded Wright at Burkart’s and other bars with hurtful comments about her friend.

She wants to clarify two things about that night: Tommie was intoxicated, but not hammered (“I’ve seen him a lot worse — a lot, lot worse”). She also insists that he never said “Fuck that gator!” in spite of the fact that LeBlanc, the only person within earshot of Tommie, told police that he uttered those words. Tabatha also thinks he said it. “When I heard about Tommie saying ‘Fuck that alligator,’ I was like, well, that sounds just like him,” she says. “Especially if he has a few beers in him.”

That leaves the question of when LeBlanc first jumped into the water: Was it before or after the alligator attacked Tommie? “She’s the only person who knows what happened,” Brian says.

Facebook messages and emails to LeBlanc’s Hotmail and Yahoo accounts went unanswered, and all phone numbers ascribed to her name were inactive. A few days after Christmas, I reached LeBlanc’s mother. “I haven’t heard from her in years. Someone said that she was now in Mississippi. She don’t have nothing to do with us,” she says. I ask if any family members still maintain contact with her daughter. “What part of she don’t have nothing to do with us don’t you understand? Nobody knows where she’s at.”

Had he been assailed by something like a pit bull — or even a grizzly bear — Tommie Woodward’s story may not have caused such a commotion. Alligators have a certain mystique befitting prehistoric beasts that can swim 30 mph, outrun humans on land, lift a small truck with their jaws, and even climb a fence. Alligators belong in Jurassic Park.

Chris Stephens, known to his friends as “Gator Chris,” has been obsessed with them since childhood. “Alligators have the strongest immune system in the animal kingdom — did you know that?!" he gushes. A nuisance-control hunter for Texas Parks & Wildlife in Harris and Fort Bend counties, he’s the man on call when someone in Houston finds a gator in their swimming pool. He would know what elements led to Tommie Woodward becoming Texas’s first fatality from an alligator attack since 1836.

“Everything that could have gone wrong did.”

“Everything that could have gone wrong did,” Stephens tells me. For starters, it was breeding season. During this period from May to September, both male and female gators become more aggressive and territorial. Another mistake Tommie made was swimming at night. Because of the nerve endings on their snout, alligators are stealth night feeders. Chemical receptors in the alligator’s mouth and jaw act like sonar in a way, allowing them to sense any chemical changes in the water alerting them to when food is nearby.

Stephens, and other gator experts consulted, believe the most important factor was that the alligator lost its natural fear of humans once customers at Burkart’s Marina fed him. “Feeding a gator once can cause it to be a nuisance for the rest of its life because it trains them to think people have food. It’s like feeding a stray cat or dog," he says. "Now, when a gator hears footsteps on the dock, it thinks, Get ready, food’s coming.” Brian admits he fed Cheetos to the smaller gators. He says he didn’t know that feeding alligators was prohibited.

More attacks are inevitable. Stephens points to the number of gators he caught in 2016: 150, a nearly 300% increase from the previous year. A week before Tommie's death, an alligator attacked a 13-year-old boy and his father at Mac Pond in Wallisville, Texas, not far from where Mr. King died in 1836. Both father and son were hospitalized. Then, in June 2016, an alligator killed a 2-year-old boy at Disney’s ritzy Grand Floridian Resort. The victim was building a sandcastle when a 7-foot gator bit his head and dragged him into a lagoon.

With developments in Southeast Texas, Louisiana, and Florida springing up around bayous, lakes, ponds, and canals, we are intruding into the alligator’s natural habitat, creating more opportunities for encounters between man and beast.

Brian drowned his sorrows in Kessler whiskey following his brother’s death. He declined interview requests, didn’t watch the news or read the paper. Already a light social media user — he lurks, never posts, on Facebook and had never heard of Twitter until I mentioned it — he went completely dark during this time. "The whole public aspect did not bother me one bit because I am not a public person and didn’t allow negativity like that to bring me down," he says. "I didn’t view it. I didn’t want to be nowhere around it." And when reporters knocked on his door, he “told them to fuck off.” He also avoided talking with family and friends about what happened.

Soon afterward, his sister Tabatha visited Orange to gather Tommie’s belongings — and attempt to comfort her surviving brother. “I feel like he was numb,” she tells me. “Brian’s emotions are very hard to read. He doesn’t show emotion like me or you. He bottles things up. He’s always been like that. But it seems like after his accident, he really cannot express emotion.”

The publicity surrounding her brother’s death, she says, robbed her of a proper grieving period. Instead of memorializing Tommie, Tabatha was busy defending his reputation. Instead of feeling sad, she felt anger — toward the media for turning a tragedy into tabloid fodder, toward the anonymous commenters exploiting her pain for cheap LOLs they’d soon forget.

“I barely recall,” one of Tommie’s Facebook trolls says when I contact her. She then offers a non-apology apology. “In retrospect, I should have realized that even stupid people have friends and family who care, and I’m sure I was in the wrong to say anything negative. However, when people do ridiculous things, and it becomes public knowledge, I think it’s pretty much human nature to immediately think, What an idiot.”

"Tommie just got to go home. I look forward to the day I get to go."

The mourners at Tommie's funeral had no such trouble extracting the person from the internet joke. A 27-minute slideshow created by Woodward’s cousin that ran during the proceedings provided a loose sketch of a life lived: unwrapping Christmas presents, family gatherings, and summers spent in the pool; baby pictures, grade school, Little League, and prom night; first steps and first loves; Tommie as an awkward teen experimenting with the kind of hairstyles (bowl cut, Bieber bangs, spiked skater-punk) worthy of both a wince and a nostalgic smile.

Brian was still enduring tough times in December, 18 months later. He recently separated from his wife, and was scheduled to serve 10 days in jail starting on Jan. 4 for his third DWI — the Breathalyzer will remain in his truck for six years, he says. He has accepted Tommie’s death though.

Back at Burkart’s Marina, standing on the pier, near where his brother spent his final moments, Brian shares how a combination of fatalism and faith help him mourn. “Losing somebody ain’t easy, but what’s done is done,” he says. “Ain’t nothing I can do about it, can’t take it back.” He takes a deep breath. “Tommie just got to go home. I look forward to the day I get to go. One day I will get to see my brother again.”

For now, he will settle for the nights when he sees Tommie in his dreams. It doesn’t happen often, and there’s no hidden meaning, nothing to analyze. What Brian sees in his dreams and what it means is pretty overt. The same scenario plays out each time. Once Tommie appears, Brian stops whatever he’s doing. He then looks at his brother, smiles, and says, “Man, it’s good to see ya.” ●

Tommie Woodward, gator attack victim last year, now has his name & picture inside the bar at the marina. @12NewsNow