When a man in the UK was cleaning his fish tank, he accidentally released a dangerous toxin.

Chris Matthews was cleaning a fish tank at his home in Steventon, England, when he removed coral from the surface of a rock. The next day he had flu symptoms, as did his entire family — and their two dogs.

Matthews, who knew that some corals used in aquariums could be hazardous, suspected that it might be the reason they were all feeling ill, so he called for help. About 50 emergency personnel, including a hazardous materials team, arrived at his home, according to the BBC.

A total of 10 people were hospitalized, including Matthews, his family members, and four firefighters.

Matthews said he was unaware of how easily the toxins could be released and that cleaning the rock in the air, rather than under water, was potentially a problem. "We did not know that doing it out of the water would release it out into the air," he told the BBC.

John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxfordshire confirmed that six people from the property and four firefighters were treated at their facility on March 26. The family is "recovering well," Matthews told the BBC, as are the family dogs, which were treated by a veterinarian.

A neighbor, Dr. Mike Leahy, a professional biologist and TV presenter, tweeted a picture of the emergency response team.

Went for a cuppa with Mum. When I left confronted by this. Trapped within police cordon. Palytoxin incident due to a neighbour cleaning his coral tank. Second deadliest naturally occurring toxin in the world (allegedly) but rarely kills, & only if eaten! Over-reaction? https://t.co/iTlpLvyXSn

The dangerous substance is called palytoxin. It can be found in some of the most common corals sold for saltwater aquariums in the US and elsewhere in the world.

The soft corals that contain palytoxin grow on rocks and attach themselves in a way that makes them almost impossible to remove without physical scraping or using some other method, said Jonathan Deeds, a research biologist at the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition in College Park, Maryland.

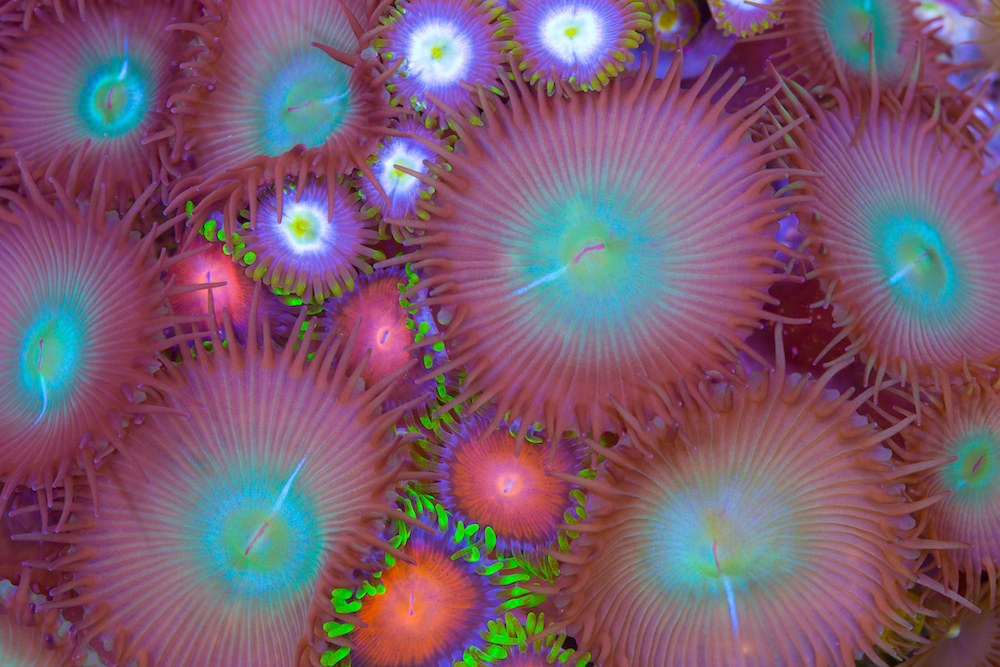

The corals are greenish-brown in color and can be invasive, grow fast, and spread in the tank.

"Basically they look like small anemones," Deeds told BuzzFeed News. "They are small and grow in a patch that are connected to each. This is the group that has historically produced palytoxin."

The toxin is usually released when people clean the tank and try to remove the growth.

"The most severe cases are when people take these rocks out of the tank and they try to trim them back by pouring boiling water over that part of the rock," said Deeds, who is an expert on palytoxin. "That causes aerosolization of the toxin." (The FDA, which oversees food and drugs, does not regulate fish tanks or these types of exposures, the agency noted.)

Palytoxin can cause severe symptoms like coughing, fever, and eye irritation.

The toxin disrupts cell membranes and can cause cells to die over several hours. Unlike other marine toxins, palytoxin can be dangerous if ingested, inhaled, or if it gets into small cuts on your skin, and the symptoms vary depending on the route of exposure.

"Right now it looks like one of the most potent ways to be exposed is by breathing it in and getting it into the lungs," said Deeds. When inhaled, the symptoms can include uncontrollable coughing, fever, headache, difficulty breathing, rapid heart rate, sore throat, runny nose, chest pain, skin redness or a rash, swelling, muscle pain, numbness or tingling, and eye irritation. The surface of the eyes, or corneas, are particularly sensitive to the toxin.

"It can definitely cause permanent damage to your eyes," said Deeds. In some cases, people have needed a cornea transplant or other eye surgery after exposure. "Those are very rare, but it has happened," he said. People have accidentally rubbed the toxin into their eyes and sometimes the corals can squirt a stream of water when they are removed from the tank.

"When you pull it out of the water, it closes up," he said. "If you pick up a rock and are looking at it, it can close up and squirt you right in the eye. So eye protection is a very good idea manipulating these things."

No humans have died from exposure to corals from a fish tank. But some dogs may have.

There have been no recorded deaths due to palytoxin associated with corals used in an aquarium, said Deeds. However, in rare cases — maybe 10 to 20 total worldwide — people have died after eating the liver or other internal organs from fish or crabs contaminated with palytoxin.

A few dogs may have died of palytoxin, but tests were inconclusive. The level of toxin that is lethal to a pet is very low, and may not have been detectable in tests. These cases probably occurred when people put the rocks from a fish tank in a container on the floor and a pet licked them.

"We haven’t been able to confirm this, but there have been a few cases of dogs dying after being exposed like that," Deeds said.

It can be hard to know if you are buying a coral that contains palytoxin.

Although Matthews believed a coral in his tank called a "pulsing xenia" was responsible, that would be unusual, Deeds said.

"I can’t say for sure unless somebody actually tests it, but it’s more likely that he had zoanthids in his tank," he said.

Palythoa and Zoanthus coral species are the most likely to have palytoxin. But aquarium stores don't generally provide scientific names, and even if they did, experts don't always agree on the number of species and what their names should be, Deeds said.

"So it’s very difficult to say 'don’t buy this one,'” he said. "The names are not standardized."

But there are some best practices to follow to avoid palytoxin when handling coral, according to a new set of guidelines released this month by the Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association, a UK-based organization.

The group recommends that people do not spray or wash rocks under running water, pour boiling water or hot water on them, or microwave rocks with live coral on them. They also recommend avoiding steam-cleaning any tank ornaments or rocks that contain what they call zoantharians, a collective name for these coral species.

If you need to remove a coral from a tank, store it in a plastic bag and close it, and soak rocks in a diluted bleach solution before disposing of them. You can find more tips on safely handling coral on their website.

Palytoxin was first discovered in the US, in Hawaii, in the early 1960s. And a Hawaiian legend led to its discovery.

A group of researchers at the University of Hawaii was looking for the cause of ciguatera fish poisoning, a different toxin that can contaminate seafood, Deeds said. The group did this by exploring local legends about what was poisonous in folklore, he said.

There was a particular pool that warriors were said to visit for seaweed that could be used to make spears poisonous.

"They discovered this tidal pool where these little anemone-like corals were growing and they discovered palytoxin," Deeds said.

In the last 10 years, interest in research on palytoxin has increased, Deeds said, particularly after a 2005 outbreak of illness on a beach in Italy was found to be due to palytoxin-like compounds, which are also produced by a type of algae. Other cases of illness associated with fish tanks have occurred in the US, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Scotland, Germany, and Australia.

UPDATE

This story was updated to clarify that the toxin is not absorbed through intact skin and to add additional locations of past outbreaks.