If the unspoken goal behind the Trump administration’s anti-Muslim actions is to intimidate Muslims out of public life, it’s backfiring.

The hostility instead appears to be sharpening Muslims’ political skills, energizing dozens of first-time candidates running for office — from school boards to Congress. At least two new Muslim-focused political action committees have sprung up, and several nonprofit groups are teaching potential candidates how to raise money, give effective speeches, and counter anti-Muslim smears.

There’s no central count of how many Muslims are running for office nationwide, but Muslim political and advocacy groups have tallied dozens of names, describing the surge as unprecedented. In Maryland alone, around 30 Muslims are vying for state and local seats, a huge leap from the three who ran in 2014, according to the Pluralism Project, a political action committee that formed this year to boost Muslim candidates. Only a handful of Muslims hold public office across the country, including two in Congress: Rep. Keith Ellison of Minnesota and Rep. André Carson of Indiana, both Democrats.

"In the next election, one cycle from now, we’re going to have candidates who have gone through the experience and they will slam dunk it.”

Hamza Khan, director of the Pluralism Project and a Democratic candidate for state delegate in Maryland, said the ugly rhetoric about Islam from President Donald Trump and his associates fueled Muslims’ interest in politics, but it’s not the only factor behind the increase. Demographic shifts in the electorate and among party gatekeepers also helped. And, Khan said, there’s simply a bigger pool of viable Muslim candidates now: US-born or US-raised men and women who’ve graduated from top colleges and emerged as leaders in their careers and communities.

The momentum is exciting to watch, Khan said, but the payoff may be a long time coming.

“The chances of these folks winning their elections is still one in three or one in five," Khan said, adding that he doubted any Muslim could "slam dunk" a race this year. “But in the next election, one cycle from now, we’re going to have candidates who have gone through the experience and they will slam dunk it.”

In interviews with BuzzFeed News, seven Muslim candidates discussed the symbolism of their runs as well as the extra pressures — and even dangers — from anti-Muslim forces determined to keep them out of office.

On the campaign trail, Muslims face death threats and hecklers interrupting stump speeches with tirades about Sharia. Candidates said they’d like to dive right into issues such as minimum wage or health care, but first must answer questions to “prove” their Americanness and loyalty. Political opponents have smeared them as Muslim Brotherhood operatives, darkened their skin in photographs, and gratuitously mentioned their faith in speeches, Muslim candidates said.

Abdul El-Sayed, a Muslim doctor running for governor of Michigan as a Democrat, has hired a bodyguard and keeps the location of his campaign headquarters secret out of safety concerns. Others complain of feeling hamstrung because they need to reach voters but worry about publicizing their events too widely. A large campaign sign for Zainab Baloch, a Muslim who ran for city council in Raleigh, North Carolina, was defaced with ethnic slurs, a swastika, and “Trump,” just days before the election this month.

The extra burdens make for exhausting, stressful days, candidates said, but they knew going in that their religion would be much more closely scrutinized than their platforms.

“It’s anxiety-provoking. The hate speech and the constant trolling,” El-Sayed said, saying he’d much prefer detailing his plans for the water crisis in Flint.

A video El-Sayed’s campaign released this month depicts scenes Americans rarely see: an affectionate, ordinary Muslim family. El-Sayed and his pregnant wife, Sarah Jukaku, are shown decorating their nursery, embracing, and cooking together.

On rough days, El-Sayed said, he thinks of the daughter he and his wife are expecting in the next few weeks. Their first child will be “ethnically half-Egyptian, half-Indian, 100% American, Muslim,” he said.

“If I can do this to make it more normal for people like her to do whatever she chooses to do, in whatever realm she chooses, it’s worth it.”

Here are a few other candidates discussing the role Islam plays as they enter politics:

Liliana Bakhtiari

Liliana Bakhtiari isn’t eager to put her identity front and center as she runs for Atlanta City Council, but these days there isn’t much of a choice.

“After Trump’s first travel ban, five members of my family who are green card holders from Iran felt the threat of deportation,” Bakhtiari said. “It was a really terrifying time period where there was nothing I could do to assure my family that they were going to be OK.”

Bakhtiari grew up working in her father’s pharmacy in the historic and predominantly African-American Sweet Auburn district of Atlanta. It was there that she credits her father, a practicing Muslim, for instilling in her the importance of community service.

And since those formative days at the pharmacy, Bakhtiari, 29, has spent most of her life working in the nonprofit world. But it wasn’t until recently that it dawned on her that despite all the work she was doing, like addressing child poverty and refugee resettlement in Atlanta, Bakhtiari was just treating what she called the “symptom of other issues.”

At the core of all these issues, Bakhtiari said, was bad or nonexistent legislation.

“I chose to run because of housing issues, I chose to run because of affordability issues, and I feel local government can be far more progressive. And you don’t need to be a queer Muslim to do that,” Bakhtiari said. “It just so happens that these things are part of my identity.”

Growing up, Bakhtiari said, she was conditioned to stay small, to think small. “And I'm tired of being small,” she said. So she decided to run for a seat on the city council.

Since launching her campaign, Bakhtiari said, she’s received calls from young people and queer Muslims, telling her how important the race is because of who she is and what she looks like. That seeing a candidate like her gives them hope, a sense of familiarity. That’s what will propel her to run again if she doesn’t win a seat this year, she said.

“There is a little girl, and her mom called me the other day and said that her daughter saw my picture and said, ‘Mom she looks like me,’ and I think that's really important to see,” Bakhtiari said.

Johnny Martin

“Johnny Martin” might not jump out as a Muslim name to Arizona voters who will see it on a ballot come November. But Martin is indeed Muslim, and his run for a state House seat is forcing the 24-year-old convert to talk about his faith more than he’d like to on the campaign trail.

“I think it's coming up because of the fact that the current administration is clearly using Islamophobia to move its agenda forward, and it's that agenda itself that is the reason I’m running,” Martin said.

"The current administration is clearly using Islamophobia to move its agenda forward, and it's that agenda itself that is the reason I’m running.”

Martin, a Democrat, hopes to work on issues including raising teacher salaries in the state and banning the use of private prisons, but he says his position as a convert, a white male in particular, gives him a unique opportunity to combat anti-Muslim sentiment or misinformation when it comes his way.

“People don’t know that I’m a Muslim when they first meet me, and that often puts me in situations that other Muslims or people of color aren’t necessarily in, and I get to hear the type of things I’m hearing,” he said.

And his religion is not the only part of his identity under attack from the Trump administration. Martin came out as queer when he was speaking at an interfaith event after the Orlando nightclub shootings.

Martin, who has long been involved in local activism, said the reason he got into politics was because he sees it as the place where tangible change can happen — and it’s where activists like him may need to start focusing more of their attention.

"In the time during the Obama administration, activism was where change was happening, and not necessarily in government,” Martin explained. “But now the government has become so dangerous, I really felt that it was important to run for office.”

Zainab Baloch

It was more “when,” not “if.”

That is how Zainab Baloch describes how she felt when she heard that an ethnic slur and a swastika were graffitied onto her campaign sign this month, just four days before the election. The words “sand nigger,” a hastily sprayed swastika, and “Trump,” were tagged in black paint across a sign touting her run for city council in her hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina.

“You have an understanding that when you live in the South, there are many people that do think this way,” Baloch said of the offensive words, something she had already experienced regularly on social media since the campaign began. “We were prepared for it, but when it actually happens, I have to say, it sucks.”

But after the incident something unexpected happened. Baloch, a 26-year-old who works for the North Carolina Division of Mental Health, said the city in which she was born and raised rallied behind her. People came out to support her — even rival candidates. “Absolutely reprehensible,” was how Raleigh’s mayor, Nancy McFarlane, described the incident.

“If 2016 didn't happen, I probably wouldn't be running for city council.”

Baloch said her team was galvanized by the hateful message. It propelled them to work harder on outreach just days before the election.

Baloch, who ran on a platform of affordable housing and increasing the minimum wage, said the word “Trump” scrawled on her sign was a reminder of why she ran in the first place.

“If 2016 didn't happen, I probably wouldn't be running for city council,” Baloch said. “If we can thank our president for one thing, it’s for motivating a lot of people to run who probably wouldn't have had otherwise.”

Although Baloch lost the Oct. 10 election, getting 11% of the vote, she plans on running again.

“That was a question everybody would ask me before the campaign and I would say I have no idea. But there has still never been a woman of color on the Raleigh City Council. And we still don’t have young people on the council,” Baloch said. “And that doesn't seem like it will change in two years, so yeah, I do want to run again.”

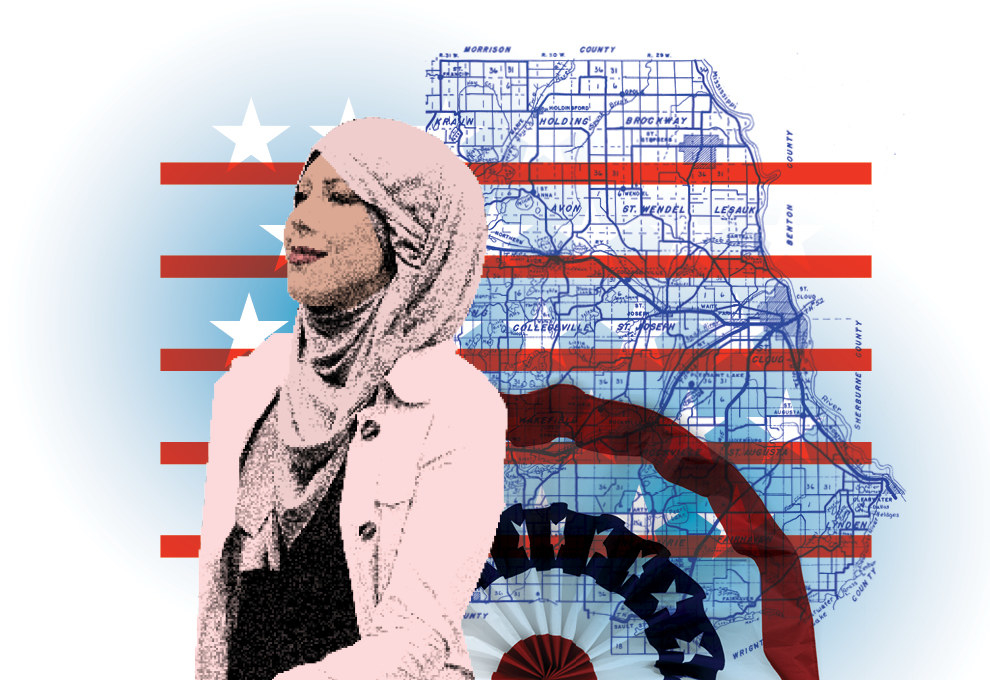

Fayrouz Saad

Fayrouz Saad, a Democrat who’s running for Congress from Michigan, is often asked whether her Arabic name is a liability with voters. If it is, she’s decided to own it. Her kickoff video begins with a tongue-in-cheek look at the many misspellings of her name on Starbucks coffee cups: Farusc, Farus, Faraus.

“They weren’t staged — they were real,” Saad said on a recent visit to Washington. “This is how you get there. You can’t try to hide it — this is how you’re going to make a change, dispel myths, and break down stereotypes.”

"This is how you’re going to make a change, dispel myths, and break down stereotypes.”

To Saad, “getting there” means having a seat in government, both to safeguard values she believes are under threat and to represent women, Muslims, immigrants, and other groups that feel vulnerable under the Trump administration. The openly anti-immigrant tenor of today’s politics, she said, is strikingly different from the America her parents encountered when they moved to Michigan from Lebanon more than 40 years ago.

The family opened a halal meat company near Detroit. Saad, age 34, and her five siblings went to public school and rose as community leaders. Saad is a former Obama administration appointee whose win would make her the first Muslim woman in Congress; she’s also served as director of Detroit’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. She trades campaign advice with one of her sisters, Mariam Bazzi, who was appointed to a county judgeship earlier this year and must run in 2018 to keep the seat.

Saad cringes at the cliché, but it’s true: Her family’s story is the American Dream. And the Trump administration’s efforts to restrict access to that dream, she said, is why she decided this was the year to pursue her goal of running for office.

“Seeing everything I was seeing at the national level, that was the push,” Saad said. “Now more than ever, change is needed. Now more than ever is the time to have a seat at the table.”

Saad announced her candidacy in July. Within 24 hours, she said, trolls on social media poked at her religion and Arab roots. They left out parts of her bio — it didn’t suit their framing that Saad spent her time at Homeland Security working on community policing efforts to fight terrorism.

In the long weeks of campaigning ahead, Saad said, she’ll try to focus on the issues and not the identity questions, though she knows it could get ugly. Her race is sure to be closely watched: Republican incumbent Rep. Dave Trott said he wasn’t seeking reelection, leaving the seat up for grabs in a Republican-leaning district the Democrats are hoping to flip. First up is a contested Democratic primary next August.

“You just hope that by continuing to run a professional campaign and to speak to your core message, you can show people, ‘I’m American like everyone else and we believe in the same values,’” Saad said.

Regina Mustafa

Not long after Regina Mustafa, a Democrat, announced she was running for Congress from Minnesota, a man claiming to be a reporter called her for an interview. After a few introductory remarks, Mustafa recalled, he began asking invasive questions about her conversion to Islam, and it became clear the call was a setup. He then screamed at her and refused to give his name.

“He got me good,” Mustafa said with a wry laugh.

"There are people who just want to shake me out of the race, but this is exactly why I need to be in the race.”

But then came a more sinister backlash to her candidacy. Mustafa opened her home mailbox and found a five-page screed about Islam from a stranger who demanded that she publicly denounce specific verses of the Qur’an. The same day, Mustafa learned that someone had left a death threat in the comments section of a video about her on YouTube. “She will be shot,” it read, along with vulgar, sexist slurs. Mustafa alerted a Muslim advocacy group and the police.

“I’ve been so used to getting anti-Muslim comments over the years, but this was the first clear-cut threat and also the nastiest,” Mustafa said. “But about 75% of me thought, Well, you knew this was going to happen and you’ve got to deal with it. There are people who just want to shake me out of the race, but this is exactly why I need to be in the race.”

Two weeks after those defiant words, however, Mustafa withdrew from the race, citing not hostility but lackluster fundraising. In a phone interview, she sounded dejected, but not defeated, vowing to run for office again. Next time, she said, she might aim for a local seat such as mayor or city council.

“I don’t regret a second,” Mustafa said. “I was able to go to various parts of the state I’d never been to. For many people, I was the first Muslim they’d ever really spoken to or had a conversation with. If I’ve humanized Islam more by my presence out in the district, it was all worth it.” ●