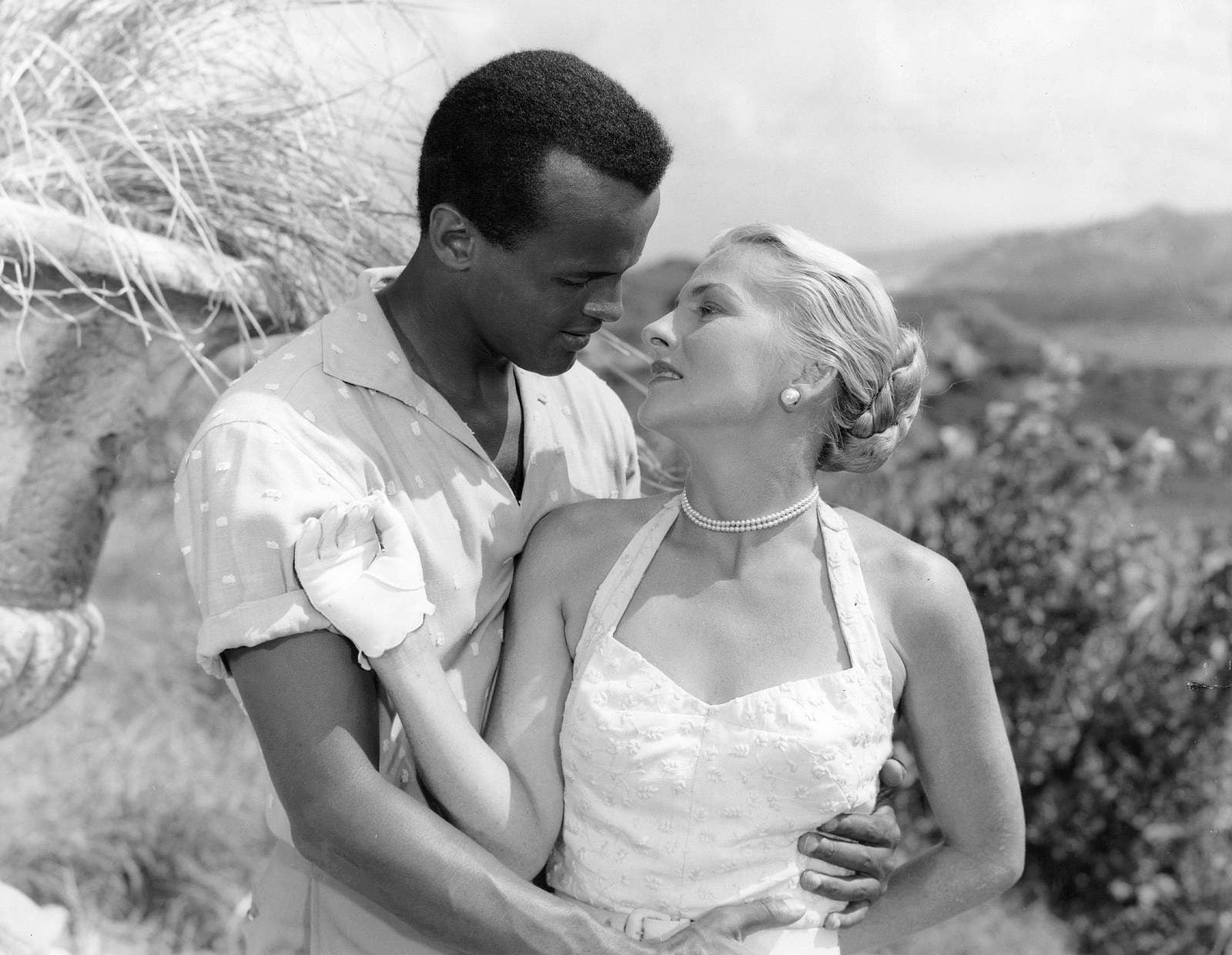

On August 17, 1957, the New York Times ran a photo of dozens of Ku Klux Klan members picketing a movie theatre in Jacksonville, Florida. Dressed in hoods and robes, with the neon lights illuminating their white costumes in the night, they marched by the popular downtown theater — unmasked. The occasion was the premiere of Island in the Sun, a film by Robert Rossen that had attracted significant media attention even before its release, because of a single, one-second kiss between actors Dorothy Dandridge and John Justin — more of a nuzzle, really. Or, as the New York Times wrote, because the cast “includes two Negroes, Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge, and part of the plot concerns them in romantic involvements with white persons.”

When the film reached North Carolina several weeks later, it put to rest any illusion of this being an isolated incident. A group of Klansmen paraded in front of the Visulite Theatre in Charlotte in broad daylight, carrying signs that read: “We protest the showing of this integrated film ‘Island in the Sun’ in N.C.” In North Carolina, too, the Klansmen went unmasked.

This month marks the 60th anniversary of Island’s release on June 12, 1957 — as well as the 50th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, the 1967 Supreme Court ruling that would declare all race-based bans on marriage unconstitutional, 10 years after Island’s premiere. Though the response to Island at the time made much of its interracial “romantic involvements,” these scenes in truth were brief, and packaged in a way that minimized imagined threats to white supremacy. But in 1957, in a cultural context that held segregation as a rule rather than an exception, even the most timid endorsements of romance between black and white characters were boundary-breaking. Making the movie was a real display of courage.

In contrast, a recent series of “tiny moments” in big movies, which have generated a lot of hype for only a little representation, show that it's much harder for a feature film to really earn the designation of being landmark or boundary-breaking in 2017. Beauty and the Beast and The Power Rangers, two of the year's big-budget, mainstream films, have been lauded as groundbreaking for their inclusion of a male-male dance scene and a queer Ranger, respectively. But both are in fact just taking small steps to decenter the white male bias that rules most blockbusters (and society). Furtive glances, clever allusions, and sometimes a little bit more went a lot further in 1957, as a way of grappling with taboos and pushing against entrenched, aggressive attitudes — even if contained to a few seconds. But in 2017, a two-second scene of LGBT representation in Beauty and the Beast does not quite achieve the same effect.

Prejudice in the United States has become much less visible since Island in the Sun was released — if not necessarily less present. Racism, sexism, and homophobia are alive and well, but there are no longer laws to prohibit interracial marriage, and the KKK does not physically bar patrons from accessing movie theaters. Filmmakers are generally not threatened with censorship, violence, or legal repercussions.

Some high-profile movies certainly do reflect and engage with that decades-long shift in cultural norms: This year, for example, Jordan Peele’s Get Out brilliantly continued (an commented on) the long struggle to cinematically depict black-white interracial dating, while in Loving we got a feature-length depiction of the eponymous Supreme Court case. Smaller productions have taken advantage of the right to free expression to explore a much larger spectrum of stories than was possible 60 years ago — from features like Moonlight and Wexford Plaza to documentaries like I Am Not Your Negro. And this month, Wonder Woman debuted as the first enormous (and enormously successful) superhero blockbuster both starring and directed by a woman.

Little gestures and second-long kisses are no longer enough to truly challenge the assumptions or prejudices of most of the moviegoing public.

But even in the absence of explicit social or legal strictures on representing perspectives and experiences outside the straight white norm onscreen, most big Hollywood movies still safely confine themselves to it. Representation remains structurally flawed, and the stories of anyone but straight white men are often either missing or invoked through stereotypes. Many big films that are notable for one kind of representation — starring (white) women — often rely on the othering of racialized characters for comedic effect.

This hasn’t stopped Hollywood from celebrating itself, and being celebrated, for tiny moments of representation, or from spinning many movies as more daring than they actually are. The industry’s self-indulgence was on full display recently in its infatuation with La La Land, a musical romance starring two hugely popular white actors that somehow managed to generate a PR narrative as a risk-taking, game-changing underdog of a movie in the same Oscars season as Barry Jenkins’ eventual Best Picture winner Moonlight, which featured a largely unknown cast in the beautiful coming-of-age story of a gay black man. And this exaggerated pat-on-the-back attitude toward mainstream Hollywood productions, as BuzzFeed News' Alison Willmore recently suggested, does more harm than good.

Many people still feel invisible in popular culture, and the pain of that extends far beyond the screen. Little gestures and second-long kisses are no longer enough to truly challenge the assumptions or prejudices of most of the moviegoing public. And so the project now — for both audiences and artists — is to find a way to genuinely embrace incremental change without losing sight of the fact that real representation deserves and demands so much more.

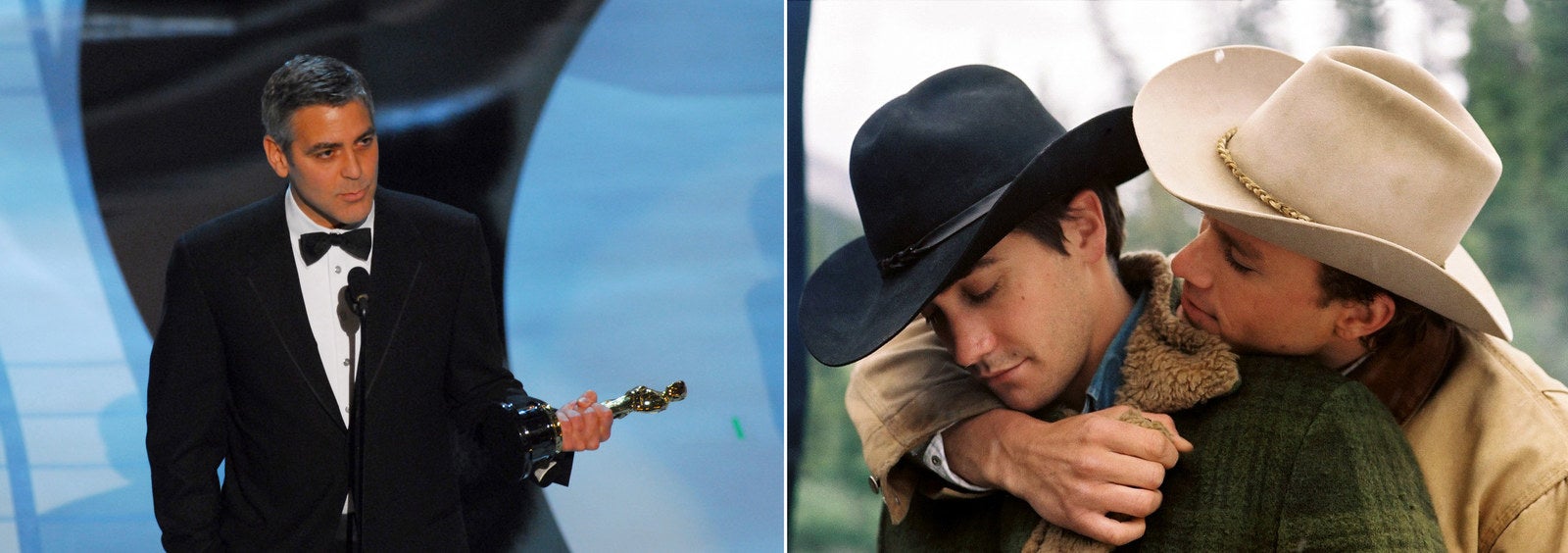

We certainly cannot rely on the most powerful people in Hollywood to tell us when celebrations are in order. When George Clooney won an Oscar in 2006 for his supporting role in Syriana, for example, he used his time onstage to congratulate the Academy on its progressivism:

"I would say that, you know, we are a little bit out of touch in Hollywood every once in a while, I think. It's probably a good thing. We're the ones who talked about AIDS when it was just being whispered, and we talked about civil rights when it wasn't really popular. And we, you know, we bring up subjects, we are the ones — this Academy, this group of people gave Hattie McDaniel an Oscar in 1939 when blacks were still sitting in the backs of theaters. I'm proud to be a part of this Academy, proud to be part of this community, and proud to be out of touch."

The irony of what might be called his Hollywood savior complex was multilayered. He had just beaten Jake Gyllenhaal for Gyllenhaal’s role in Brokeback Mountain as “half of one of the screen’s most precedent-setting couples,” in presenter Nicole Kidman’s words. Clooney, on the other hand, played a CIA operative dispatched to guard US oil interests against Chinese competitors and Middle Eastern terrorists. From the vantage point of 2017 and the past two years' #OscarsSoWhite campaigns, his victory doesn’t register as particularly progressive — and it didn’t at the time, either.

As Spike Lee said of his reference to McDaniel, “To use that as an example of how progressive Hollywood is is ridiculous. Hattie McDaniel played MAMMY in Gone With the Wind. That film was basically saying that the wrong side won the Civil War and that black people should still be enslaved.” Exactly how “out of touch” Hollywood still was became obvious again just two years later, when Robert Downey Jr. was nominated for an Oscar in the same category for his role, in blackface, in Tropic Thunder.

A pretty small fraction of the many people in Hollywood who fancy themselves progressive are actually creating or greenlighting films that clearly reflect those attitudes in their content or casting.

It’s tempting to read the kind of self-congratulation that surfaced in Clooney’s speech as betraying an industry-wide insecurity that it is not enough to focus exclusively on “merely” entertaining. Beginning in Hollywood’s Golden Age, when the industry governed itself via a production code (1930–1967), executives had — or at least said they had — something bigger in mind. “Motion picture producers know that the motion picture within its own field of entertainment may be directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking,” the code’s preamble held.

This noble goal in reality led to numerous restrictions on filmmakers. But many actors and directors today still do want to contribute, change society for the better, or at least create something more lasting than two hours of fun. And this translates into the much-publicized idea of Hollywood as generally politically progressive, much to the ire of people like Sarah Palin, Tim Allen, and Donald Trump. Allen went as far as saying that Hollywood “is like ’30s Germany,” while Trump notoriously went after Meryl Streep when she criticized his xenophobic and ableist rhetoric at this year’s Golden Globes.

In fact, a pretty small fraction of the many people in Hollywood who fancy themselves progressive are actually creating or greenlighting films that clearly reflect those attitudes in their content or casting. Only 7% of mainstream films managed to meet what the Annenberg Foundation calls racial/ethnic balance, an approximation of national population demographics in its casting practices. The number of Hollywood films featuring diverse casts is not increasing, per the popular narrative, but decreasing.

But for every representative of the studio system who acknowledges that there’s a lot of work to be done, there’s a proud defender of Hollywood’s supposed enlightenment. Lionsgate Co-President Erik Feig applauded his company for making many “left-of center decisions,” citing La La Land, The Hunger Games, Twilight, and “a Tyler Perry comedy” as examples of “unconventional bets” the studio took. Those movies may be left of center, but they’re still not very far from it.

Many powerful producers claim to walk a tightrope between representation and marketability, leaning on the idea that too-overt moves toward diversity will scare away audiences, or that no actors of color with the same box office appeal as white stars are available.

“I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such,” Ridley Scott infamously said when critiqued for whitewashing Exodus: Gods and Kings. When controversy over Scarlett Johansson’s role in Ghost in the Shell erupted this year, director Rupert Sanders also pointed to international bankability to defend the casting, saying that “we’re making a global version of the film, you need a figurehead movie star. The world basically cast Scarlett Johansson.”

Meanwhile, Johansson herself deflected attention from the whitewashing accusations by pointing to the fact that a franchise with a female protagonist was “a rare opportunity.” But highlighting the film’s contributions to diversity in one area (gender) to counter criticisms about its conceding to the status quo in another (race) falsely casts diversity as a zero-sum game. Furthering inclusion and representation does not mean switching in a woman for a man, or a black character for a South Asian character, or other forms of tokenism. It is not enough to work on improving only one aspect of representation, like gender. Those who are disadvantaged in one aspect are privileged in others, which is also why not everyone is elated about Wonder Woman’s achievements and its treatment of women of color.

With so many stubborn and inaccurate excuses for keeping Hollywood’s status quo firmly in place, we find ourselves in a topsy-turvy situation where even fleeting moments of representation have been celebrated (or protested) as transgressions. This spring, both the Power Rangers sequel and the live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast found themselves engulfed in media storms over their brief scenes with LGBT content. Much was made of the films being banned, or the “offensive” scenes censored, in foreign locales like Russia, Kuwait, and Malaysia.

One drive-in theater in Henagar, Alabama, also decided not to screen Beauty and the Beast because of what director Bill Condon called “a gay moment” where Josh Gad’s LeFou rotates to a male partner in a dance scene. But despite the vocal minority, a majority of Americans (68%) have no problem with LGBT relationships, and 55% of Americans support marriage equality, which makes the coverage of reactions to this two-second scene seem overdrawn compared to the KKK protesters Island in the Sun faced in 1957.

To achieve what Island in the Sun did in a single second in 1957, today’s films need to do a whole lot more.

The counter-reaction to defend and applaud Beauty and the Beast was also exaggeratedly loud, at least until audiences actually saw the moment in question. “Beauty and the Beast Will Make History by Featuring Disney’s First Gay Character,” Marie Claire proclaimed. The film was also praised for including the first two interracial kisses in a live-action Disney film — which, in fact, wasn’t accurate.

It becomes a problem when “tiny gestures” are celebrated or debated as if they’re truly changing the playing field, as opposed to cautiously setting foot on a playing field that’s already changed. That two-second shot, in an otherwise very heteronormative girl-meets-prince story, is a cool touch. But two seconds of LGBT content should be the bare minimum in any film that wants to offer a representational or aspirational image of society.

To create a movie in 2017 that’s truly courageous in what it depicts takes deeper and more sweeping commitment to a particular vision — whether it's a movie that addresses the very elusiveness of prejudice, like Get Out, or movies that place representation at the center of their casting and crew decisions by employing people of color in all roles, like Crazy Rich Asians or Black Panther. To achieve what Island in the Sun did in a single second in 1957, today’s films need to do a whole lot more.

Daring to risk repercussions by tackling a taboo by no means translates into a perfect film, then or now. Island in the Sun certainly reflected concessions to prejudice and is full of moments where its racial politics are painfully outdated. But it did press at the core of what America believed about itself, forcing people to confront their limited views about who belonged and who did not, and who could desire whom.

In Island — a story centered around a rich white family living on a fictional Caribbean island under British colonial rule — Harry Belafonte plays a local labor advocate, and is seen spending a lot of time with a white socialite played by Joan Fontaine. It is only at the very end of the movie that filmmakers conceded to the popular obsession with white female purity by having Belafonte reject Fontaine’s advances. “If I were to walk into a room with you or a girl like you as my wife...I’d be a fool,” he says. “It’d be inevitable. That night she’d forget herself and call me a nigger.” The film calls out racism here, but at the same time carefully detonates any threat of black male sexuality.

Gender also clearly played a role in the other interracial pairing in the film. While the plot doesn’t exactly revolve around the romance between Dorothy Dandridge’s character, a black drugstore clerk, and John Justin’s, a white aide to the governor, it does grant them a future together — after their controversial kiss, they depart for London to start a new life there. White men, in other words, can play by different rules.

The frequency with which other interracial pairings made their way onto the screen before and after Island made it clear that it really was blackness, above all, that mattered to the white supremacist majority that claimed to represent the nation. Onscreen relationships between white men and Asian women, such as the first film adaptation of Madame Butterfly in 1932, were a well-established trope. West Side Story, featuring a romance between a white and a Puerto Rican teenager, opened to great Broadway acclaim the same year Island appeared, and the 1961 movie version broke records. These depictions didn’t necessarily offer much in the way of favorable representation; they firmly occupied a white male gaze, objectifying women of color (or, worse, white actors intended to look like women of color). But they did signal that the status quo wasn’t threatened by those pairings in the way that it was by black characters falling in love with white ones.

The KKK’s campaign and larger public outrage over Island, then, were directly tied to deeply entrenched social and legal attitudes about black-white relationships at the time. As Henry Popkin of Commentary Magazine wrote upon the release of the film, “Negro miscegenation was the last to appear on the screen because it is the real issue, the most meaningful to Americans.”

In fact, Island was the first film that could feature an interracial kiss. Film production in Hollywood was almost exclusively governed by the Production Code Administration. In attempt to avoid direct government censorship, Hollywood studios themselves devised a list of regulations, and if filmmakers wanted their movies screened in any theater in the country, they had no choice but to comply. From 1930 until 1956, the PCA explicitly stated that “miscegenation (sex relationship between the white and black races) is forbidden.” This was one of only two instances in which the code explicitly used the word “forbidden.” Even for rape, abortion, and blasphemy, there were special provisions that could justify their presence onscreen.

Back in 1957, some theaters tried to cash in on the aura of illicitness that surrounded Island. In Wetumpka, Alabama, the local theater lured people by advertising that “This is the one that is banned all over the South. While we dare show it, we do not endorse it.” This particular ploy for ticket sales backfired: A mob of 200 white locals, some affiliated with the White Citizens Council, blocked the entrance and cut the theater’s power. The New York Amsterdam News reported that the owner of the Dixie Drive-In and his wife had to flee through a cornfield to seek police protection.

By featuring not just one but two black-and-white romantic pairings, then, Island came out with guns blazing. And Island’s creators did not cave under pressure; they were set on bringing the issue before audiences. Producer Darryl F. Zanuck said that attempts to prevent or penalize screenings of Island threatened to “destroy not only our theaters but our American institution of freedom,” while 20th Century Fox firmly stated that they would “not be making any cuts to the film.” In 1957, that was what courage looked like. And Island, even if its most controversial scenes were mere moments, really did deserve the designation “landmark.” But as the social context in which movies operate has changed, so has the impact and meaning of these moments.

This year also marks the 50th anniversary of 1967’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which in many ways built on what Island in the Sun’s creators had dared to bring to the screen 10 years earlier, and the differences between the two movies trace an arc of changing cultural attitudes. Stanley Kramer’s drama-comedy about interracial marriage — in which self-professed San Franciscan liberals played by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy are made to reconcile talk with actions when they realize that Sidney Poitier is more than just their daughter’s very well-educated doctor friend — was hailed at the time as a “landmark.”

In reality, it was equal parts revolutionary and nonthreatening. As Roger Ebert writes, in order to get there, Kramer’s treatment of interracial marriage is “insulated with every trick in the Hollywood bag.” Poitier is a cipher, a black man who has to be too good to be true in order to be good enough for their mediocre white daughter, Joey (played by Hepburn’s niece, Katharine Houghton). Even then, it is not until patriarch Spencer Tracy agrees to the romance that Joey and John’s future life can take full flight — in Switzerland, of course, because the idea of mixed babies within the United States remained firmly taboo.

But the white parents in the movie do, eventually, accept Poitier as their son-in-law. And this was remarkable, considering that interracial marriage was still illegal in 17 Southern states when Kramer shot it. The Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court ruling was not passed until June 1967, just a few months before the film’s release. A 1968 Gallup poll showed that societal sentiment was even harder to change than law, with only 17% of white respondents expressing approval of “marriage between whites and non-whites.” This April, lead actress Houghton recalled that Columbia Pictures was reluctant to shoot Guess Who once they realized its subject, doing “everything they could to stop filming.”

Of course, that does not mean that we need to uphold Guess Who as a model of progressive politics. The film also included descriptions of the entire continent of Africa as undeveloped, and an inexplicably out-of-context and lengthy scene of an orientalist bar with waitresses in kimonos. And it certainly didn’t put an end to — or even make a significant dent in — anti-black racism in the US (something no single interracial relationship, or depiction of it, is likely to do). But the film was a milestone in depicting black-white relationships onscreen (“a kind of a thunderbolt,” Houghton said), and it shows the way in which changing cultural context can slowly but surely raise the bar of what’s required for a movie to truly push representational boundaries.

It is also a good reminder that the knee-jerk impulse to defend contemporary movies that make well-intended gestures toward inclusion from any criticism is misguided. We need to simultaneously be more discerning and critical about what exactly it is that we are applauding, accept that all movies are created by mere mortals, and keep asking for more.

One film this year — Get Out — acted as a kind of coda to the conversation about interracial relationships that Island and Guess Who began, and shows what it looks like when a filmmaker is truly able to take risks and commit to a project outside the “center” of Hollywood’s field of vision. Jordan Peele’s satirical horror movie brilliantly parodies the benign racism of Guess Who by borrowing its narrative premise: What starts as an awkward yet fairly ordinary meet-the-parents weekend for Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a black photographer, quickly devolves into something much more sinister when his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) and her self-professed liberal parents turn out to be anything but. In an all-too-real nightmare, Chris slowly comes to realize that he is not a guest, but a deliberately selected victim.

Get Out navigates the legacies of racism and interraciality without any concessions or romanticizing. The fake liberalism of San Francisco (or Hollywood), this movie suggests, may be no better than the overt racism of the US South. Here is a film that is not meant to be comfortable for everyone.

And yet Get Out was met with near universal critical acclaim and is widely regarded as an early Oscar contender — a rare distinction for any horror film. It also powerfully dispelled the myth that “niche” films don’t make money, or that films uncompromisingly committed to diversity will alienate moviegoers; the film has grossed more than $250 million worldwide on a $4.5 million budget.

Diverse casts and stories can absolutely translate into big critical and commercial successes.

Productions across the entertainment industry — like Hamilton, Insecure, Master of None, Atlanta, Hidden Figures, and Moonlight — have also shown that diverse casts and stories can absolutely translate into big critical and commercial successes. Recent hit blockbusters like Star Wars: The Force Awakens, with its diverse cast, and Wonder Woman are encouraging leaps in the right direction. And despite some attempts to boycott Star Wars for its “anti-white” focus, to boycott Rogue One for its multicultural agenda, and to disrupt all-female screenings of Wonder Woman for their “sexism,” these films' successes are only some of the recent evidence that the audience and appetite for representation now — much more so than in 1957, when Island came out — outweighs the reactionary, bigoted forces against it.

This isn’t just a question of representation and equity, but also profit. According to the Motion Picture Association of America, Asian-American moviegoers were better represented than any other group at the box office last year, and the number of African-American frequent moviegoers — meaning those who see a movie at least once a month — doubled in 2016. There is a huge potential there, and it certainly does not lie with the whitewashing ways of Ghost in the Shell, Iron Fist, or Aloha, or the casual yellowface of Ab Fab: The Movie, all of which uncoincidentally bombed.

So it’s frustrating that so many producers of mainstream feature films still seem afraid of representation, and that we keep patting them on the back for doing the bare minimum. As Stacy L. Smith, director of the Media, Diversity, and Social Change Initiative at USC, said, “While the voices calling for change have escalated in number and volume, there is little evidence that this has transformed the movies that we see and the people hired to create them.”

There is an immeasurable difference between merely checking boxes and sensitively and deeply engaging with perspectives, storylines, and crews that are not white or male or straight. Filmmaker Dee Rees, whose debut Pariah and subsequent HBO film Bessie centered queer women of color, identified Hollywood’s selective memory as one cause of its inability to move beyond the status quo. “It’s a perpetual shock to the industry when the next film by or starring women and people of color succeeds,” she said.

Over and over, writers and producers seem to approach more representation, only to pull back. Television seems no less prone to this than movies; take series like The 100 or Arrow or The Walking Dead, or even Pretty Little Liars, all of which were lauded for including LGBT and POC characters — only to then kill them off, or merely grant chaste kisses where straight characters got to do a whole lot more. A slew of TV shows have been canceled over the past few weeks, from Pitch to Sense8 to The Get Down to Underground, with the main common denominator that they all had primarily non-white casts or non-male leads. They were all, as Maureen Ryan notes, “the kind of programs that, from an inclusion standpoint, Hollywood leaders have repeatedly said they want to make.”

So rather than congratulations, caution seems to be in order. Hollywood and its producers are still not “the ones” George Clooney proposed 10 years ago. But they could be. As Constance Wu, one of the most outspoken actors on the importance of representation, told Vulture last year, studio executives say, “‘Uh, you know we try, but it’s so hard,’ and it’s like, Why has that ever been an excuse for doing something great? It’s like, Boo fucking hoo, a lot of shit is hard. Care more, make it matter.”

This also means a shift in attitudes about what goes on behind the cameras. Just this month, The Hollywood Reporter wrote that it was “obviously a big gamble” for Warner Bros. to hire Patty Jenkins to direct the $150 million Wonder Woman, with her only previous film credit being the $8 million Monster (never mind it winning an Oscar). TV producer Michael Schur was quick to point out the irony, given the gambles of similar size often placed on male directors without any visible hand-wringing.

THR posited before the movie’s release that if “Wonder Woman turns out to be another Catwoman, the superhero universe could remain a boys club for eons to come.” But why was the success of Wonder Woman held up as a barometer for how female directors will fare? As Wu pointed out in an open letter about The Great Wall, female, LGBT, or POC cast and crew are seen as risks, and the successes or failures of one are placed on all of their plates, yet white men are allowed to fail left, right, and center without anyone but them, individually, seeing the repercussions.

Making it matter requires effort. It is not enough to have a Jordan Peele, an Ang Lee, a Patty Jenkins, or an Ava DuVernay, no matter how incredible they are. White men get to tell their stories onscreen from hundreds of perspectives each year — their anger, their love, their hurt, and their ambitions are portrayed in great nuance, from every imaginable class position and geographic background. They are never expected to represent all white men yet assumed to hold universal value and appeal. And the depiction of those in the periphery of these white male stories can be, as Jessica Chastain said at Cannes when speaking about the portrayal of women, “disturbing.”

Rather than having to bear the burden of representation, acting as symbols for groups that encompass rich and divergent fabrics, these other perspectives need to be shown in all their nuances, alliances, and antagonisms. It is no longer enough to show two seconds of something transgressive if you are not really going to explore what it means and honor it. Two seconds does very little to combat the erasure of the many who fall outside the established norm in Hollywood. To chip away at that norm requires different tools than in 1957. It is not just the quantity of representation that matters, but, crucially, the quality as well. ●

Suzanne Enzerink lives and teaches in Providence, RI, where she is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies.