The first thing my mother taught me to make was the Toll House recipe for chocolate chip cookies. She handled the oven, but the rest was simple enough for an 8-year-old. Two sticks of softened margarine — this was 1990, after all — creamed with two eggs, equal parts brown and white sugar, and a teaspoon of vanilla extract. Two and a quarter cups flour, one teaspoon salt, one teaspoon soda. Pour dry into wet, dump chips in last, bake 9 to 11 minutes until golden brown. Before long I knew all the measurements by heart.

During my junior year abroad I made a version of these cookies in my British dormitory kitchenette, using a souvenir beer glass in lieu of measuring cups and the sole teaspoon my roommate and I kept by our electric kettle. I measured one full pint of flour and one half-pint of white sugar. I googled Celsius baking temperatures and discovered that British supermarkets stocked eggs unrefrigerated, but this was somehow not a health hazard. The cookies came out too flat and too pale, but I was homesick and they were close enough.

My roommate looked at me in horror when she learned how much sugar and butter had gone into the dough. She’d grown up in Hong Kong, where it’s common to have hired domestic help, and hadn’t done much cooking for herself.

“That's why they taste good,” I said, dunking an anemic cookie into my milky tea.

That’s when I realized that by teaching me how to read a recipe, my mother had given me a wonderful lifelong gift: the ability to bring something I crave into being with my own hands, and to share that thing with others. To put things on the table as I want them to be. To make home, and find it, anywhere I go.

By teaching me how to read a recipe, my mother had given me a wonderful lifelong gift: the ability to bring something I crave into being with my own hands, and to share that thing with others.

I’m not particularly sentimental about most of the foods I grew up with. I know that one day, when my mother is gone, I’ll see spaghetti carbonara on a restaurant menu and picture her making it over our old olive-green countertop, glancing down at a heavy, stained cookbook after a long day on her feet. But more than any one special dish, the physical rituals of cooking — the careful separating of eggs and the dirtying of multiple bowls and the licking of spoons and the placing of clean-ish dish towels over rising doughs — make me feel close to my mom.

As a teen, I spent hours unattended in the kitchen amusing myself while my mother was at work or grading papers. My sweet tooth, coupled with her early insistence that if I could read, I could cook, emboldened my experiments with layer cakes, buttercream frosting, and yeast breads from scratch. My guide through all this was our family’s kitchen bible, the Joy of Cooking. It’s wonderfully detailed, with an encyclopedic index and lengthy treatises on every culinary technique imaginable. (“There are, proverbially, many ways to skin a squirrel, but some hunters claim the following one is the quickest and the cleanest,” prefaces a series of disturbing hand-drawn diagrams.)

Joy recognizes that learning to cook is like learning a language. You start with the verbs — beat, cream, knead, fold, zest — and move on to more complex constructions: whip until stiff peaks form, let stand until foamy, cook until the soft-ball stage. As you learn the inflections of the kitchen, you understand where there’s room for poetic license — a splash of bourbon in the batter, limes for lemons, a shake of those mysterious red flakes someone brought back from Turkey — and where there isn’t.

When I was last home for the holidays, my mom gave me a copy of the Viola Cook Book, a pamphlet of recipes from her mother’s tiny Tennessee hometown that was originally published in 1945. If Joy is the patient teacher who writes everything out carefully on the blackboard, the women of Viola are like my college Russian 101 professor, who started our first class with “Zdravstvuyte!” and didn’t utter a word in English for the next 45 minutes.

The Viola Cook Book contains ingredients and measurements, but very few verbs. “Use this recipe when you want an especially fine cake,” Mrs. Rufus Wooten offers, without giving any indication of what to do with the specified quantities of flour, sugar, butter, sweet cream, baking powder, egg whites, and “flavor to taste.” “Use sweet milk, lard, and pinch of salt and flour” is the entirety of Mrs. Willie Haston’s instructions for pie crust. (The detailed recipes submitted by Ida Ramsey, who went on to write several cookbooks of her own, are a notable exception.)

The book is simply an artifact of a different time, when your mother taught you what “cook hog’s head and feet together until perfectly done” meant, and “use any favorite icing” would have called to mind a couple of obvious options.

Like language, cooking is a tool I use to shape my world. I cook to understand people better, shamelessly borrowing their dishes, and I cook so that I can be known.

I learned to make borsch while spending a good chunk of my twenties in Ukraine and Russia. (Not borscht, the way American Jews say it, but bor-shh, the way it’s written in Cyrillic, I explained to anyone who would listen.) I sat at kitchen tables and scribbled down notes as my host mothers dictated their recipes, and for a few years after I came back to the States, stick-to-your-ribs red borsch was my signature dish.

I claimed challah after I was assigned to cover a Hasidic Brooklyn neighborhood for a journalism school reporting class. Baking a traditional Jewish bread from scratch instead of transcribing interview tape felt like virtuous procrastination — true method reporting. I loved the rhythm of kneading a smooth dough, waiting through multiple rises, rolling out six long snakes and braiding them together under the tutelage of a pleasant Orthodox grandmother on YouTube. I’d never been to a Shabbat dinner, but I produced beautiful, glossy challahs that impressed actual Jews, loaves laced with apples and honey, figs and sea salt. I started bringing them to every potluck: six for Friendsgiving, four for a baby shower.

When my parents came to visit me in New York, my mom and I made both of these adopted favorites together. When I came home last year, I made challah with my nieces, showing the 6-year-old how to chop figs with a serrated knife while the almost-3-year-old insisted on dusting her fingers in the flour.

Like language, cooking is a tool I use to shape my world.

I do not call my mother as often as I should. We live on opposite coasts, separated by the three-hour time difference and her role helping care for my brother’s kids. She is often busy driving the girls to ballet, or putting dinner on the table. I am busy with my job and friends and hobbies, but sometimes when I don’t call I am simply busy being alone, enjoying my own company. It’s hard to be there when I’m here. We wave to each other on the video screen a few times a month, but these conversations are more like status checks — I’m alive, I’m traveling for work, they’re alive, they went to the park — than an intimate exchange.

When we have a kitchen to share, it’s simpler. Let me show you. This is what I eat now. This is the cooking blog I love. This is where I shop. This is who I feed.

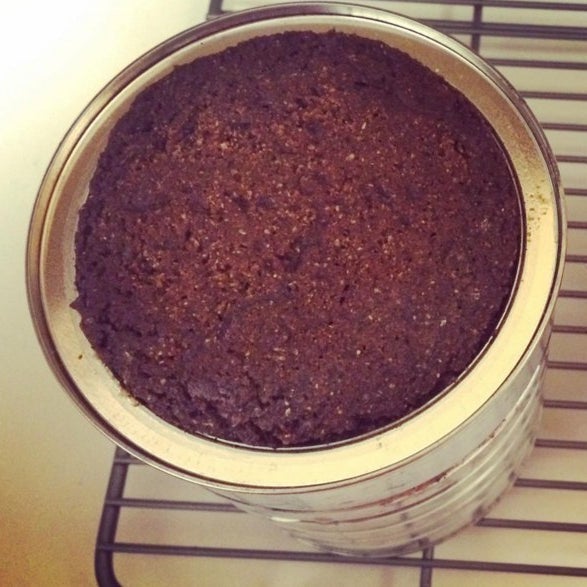

I started Instagramming my favorite quaint old recipes from the Viola Cook Book a few months ago, and eventually decided I’d try to make some of them myself. I followed my great-grandmother’s instructions to steam brown bread in a coffee can for three hours and produced something that tasted hearty and a bit like homework — good fuel for a day of farm labor. I made one chess pie that wouldn’t stop wobbling and burned another. But mostly things came out OK. Where directions were sparse, my mother’s training and my years of baking experience helped fill in the gaps. Mrs. Ramsey's lemon icebox pie got rave reviews from my colleagues and Mrs. Wooten’s cake was, indeed, especially fine.

Unlike the wives of mid-century small-town Viola, I live in a time and place when women aren’t assessed on our culinary skills and gourmet cooking is a status hobby, embraced increasingly by men. I’m in New York, where Sex and the City’s Carrie famously used her oven for storage and Seamless options abound. I love the oohs and ahhs I get when I bring a gorgeous dessert to a party, but nobody will think less of me as a lady if I don’t. Sometimes I make a cake called Blueberry Boy Bait, but I’m not doing it to catch a man.

“If I want pie, I can buy it,” SATC’s Miranda tells the girls over brunch, irked by her housekeeper Magda’s gift of a rolling pin. I can, too — but when I pour ice water into flour to form pastry dough or poke a toothpick into a cake to see if it’s done, I feel the quiet, simple joy of exercising my mother tongue. I don’t need to speak the language of the kitchen as urgently as my ancestors did, and it’s one that has changed and will continue to evolve over time. But the basic culinary vocabulary I inherited from my mother helps me fill my home with friends. It allows me to connect to communities that feel foreign and long-dead relatives I never got to meet.

Armed with that knowledge, I can test the 1970s Soviet recipes printed on the set of postcards I collected from grandmothers at Russian flea markets. I can create moments like the sunny summer afternoon I remember in Ukraine, when the streets were flooded after a quick, walloping rain. I walked past a group of ladies sitting on a bench in the courtyard in my galoshes, cradling a warm pan of lemon bars to take to my friends, and they stopped me to say, “What have you got there, a pie? Don’t you teach at the school?”

With the kitchen skills my mother gave me, I can show her she taught me something worth knowing. I can help show the next generation of my family: We are a people who mix and fold and roll and knead.