On June 16, 1961, the Soviet ballet star Rudolf Nureyev slipped away from his KGB minders while on tour in Paris, and within a week, he was doing his jetés and echappés in The Sleeping Beauty with a French company. Ten years later, 13,000 Jewish refugees left the Soviet Union; over the next three decades, the U.S. accepted hundreds of thousands. In 1979, when Bolshoi dancers Valentina Kozlova and Leonid Kozlov ducked out the garage door of the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, the U.S. granted them asylum the next day.

Today it's not ballerinas and Jews fleeing Russia in droves, but a new group of Putin-era refuseniks: LGBT people. Facing a discriminatory new law against "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations" and a spike in homophobic violence, many see getting out of Russia as a matter of life and death.

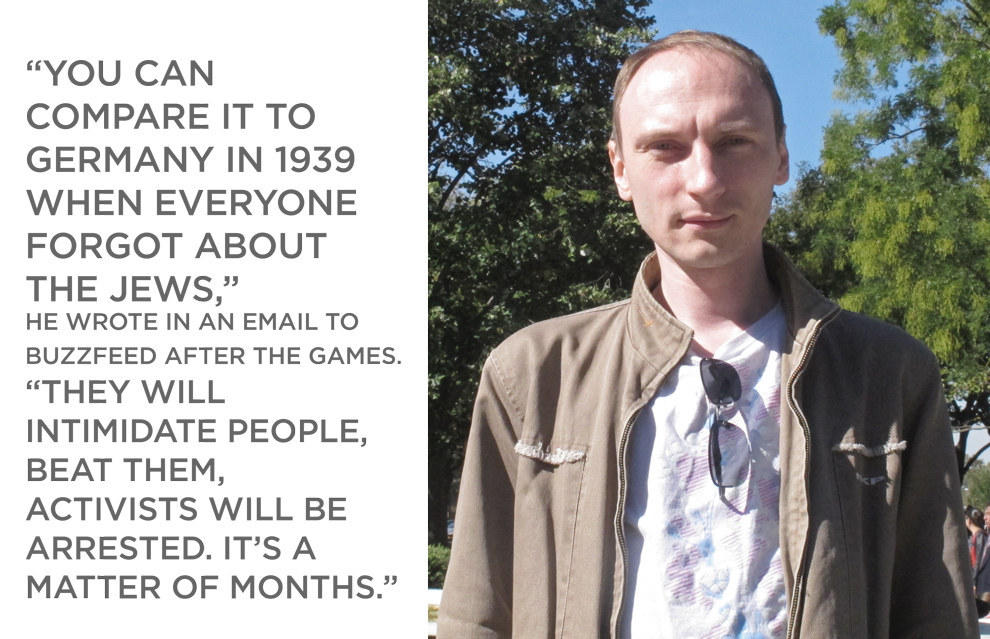

Slava Revin, a 31-year-old activist who arrived in the U.S. in July, is part of a fast-growing community of young LGBT Russians who've flocked to New York, Washington, D.C., and other U.S. cities. Like the Soviet Jews and dissidents who fled decades before them, Revin and his peers have formed a tight network, helping one another adjust to life in America and advocating for the rights of those left behind.

"I can't just come here and keep my mouth shut," said Revin, who has spoken about threats against Russian LGBT people in a video for Freedom House and called on Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter to terminate the sister-city relationship with his hometown, Nizhny Novgorod.

Revin sat down with BuzzFeed a few months ago in Washington's historically LGBT-friendly Dupont Circle. Not long after he escaped Russia, where gay bars often operate underground, he found himself living down the block from Larry's Lounge, a neighborhood spot with an outdoor patio and a neon rainbow sign.

In June, after someone he believes is a police officer threatened him online, Revin filled a suitcase with documents — records of his LGBT rights activism and work supporting HIV-positive men, copies of letters he'd written to local officials, his passport, his birth certificate — and some clothes. He called his parents and told them he was going away for a while. Then he took a train to Moscow.

Revin had made plenty of trips to the Russian capital in the course of his activist work, but this time he knew he wasn't going back to Nizhny Novgorod. He spent the night at a friend's apartment, the first in a months-long string of temporary homes. A few weeks later, with a tourist visa and an invitation to attend a conference in the U.S., he boarded a flight to JFK Airport. After he arrived, he emailed Immigration Equality, an organization that assists LGBT asylum seekers from around the world. He needed a lawyer and a place to stay.

Revin's message joined a deluge of inquiries from other LGBT Russians looking to settle in the U.S. Immigration Equality says calls and e-mails about asylum shot up after the "propaganda" ban passed last summer. In 2013, the organization opened 28 new Russian asylum cases, an all-time high compared to the previous average of 11 per year. In January, the group hired a Russian-speaking staff member to help deal with the influx. Immigration Equality currently has 44 Russian cases open and has won asylum for eight LGBT Russians since August.

Citing a long waiting list for legal help, and hoping it would be easier to find housing outside New York, Revin moved to D.C. There he secured a room and pro bono counsel through the Center Global, a program of The DC Center for the LGBT Community. In a statement, Immigration Equality Legal Director Aaron Morris said the organization is almost always able to secure representation for its clients, though it can take a few weeks.

Revin also sought contacts and advice from the Russian-Speaking American LGBT Association, the only organization in New York that focuses on supporting the Russian-speaking LGBT community. Yelena Goltsman, the group's founder and co-president, said she receives three or four emails a week from LGBT people who are thinking about leaving Russia. She sees it as a sign anti-LGBT sentiment is intensifying.

"People don't just get up and leave their country," she said. "LGBT people are basically [the] new Jews."

Revin uses the same metaphor. With the media spotlight of the Sochi Olympics gone, he anticipates further crackdowns. "You can compare it to Germany in 1939 when everyone forgot about the Jews," he wrote in an email to BuzzFeed after the Games. "They will intimidate people, beat them, activists will be arrested. It's a matter of months."

Goltsman, 51, lives the life many Russian-speaking asylum seekers hope to find in America. She was married to a man when she emigrated in 1989 from Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, where homosexuality and religion were banned and state-sponsored anti-Semitism was pervasive. In the U.S. she was able to openly express her Jewish identity, as well as her sexual orientation, and eventually came out to her family.

Goltsman fell in love with a woman she met at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a West Village synagogue led by a lesbian rabbi. In 2011, her adult children joined her under a chuppah as she married Barbara Freedman before 120 guests. The Jewish ceremony took place at a refurbished brass foundry in Brooklyn, and the reception featured a massive amount of Russian food. The couple legally became spouses under New York State's Marriage Equality Act.

Goltsman, who calls her personal journey a miracle, points out that she left the USSR with relatives and knew she could count on Jewish organizations in America for support. She's trying to build a similar community for today's LGBT asylum seekers, many of whom are single young men navigating the transition largely on their own.

When Revin arrived in America, he knew he would need a lot of help to start over. He didn't understand much English and had limited cash, but for the first time in weeks, he felt safe. "You run and run and run for a long time," he said of the decision to seek asylum in the U.S. "You're winded, but you breathe and you understand you don't have to run anymore."

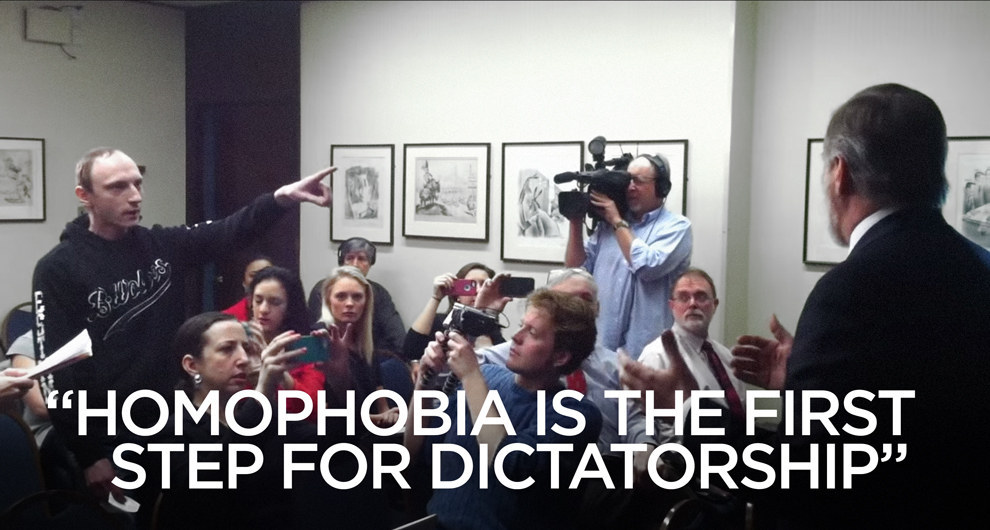

One afternoon last May, not long before he left Russia, Revin stood with 20 or so other demonstrators in Moscow's Gorky Park. He had taken the train from his hometown to protest the "gay propaganda" bill, which would pass unanimously the following month.

He held a poster that read "Homophobia Is a Cover-Up for Dictatorship" and listened as the protest organizers delivered their opening statement to the press. Everyone expected what happened next. A police horn blared. The cops started detaining the protesters — and a few of the angry young men with shaved heads who rushed to attack the demonstrators with pepper spray. Two officers dragged Revin toward a waiting police bus.

"I think they're working either with the police or with the authorities," he said of the people who heckle and assault protesters at LGBT rallies in Russia. "[The authorities] tell them that they need to act, or they leak information, or they egg them on or they pay them."

Even nine months after leaving Russia, Revin still finds himself walking in the other direction when he sees cops in D.C. On one level, he knows he can let his guard down, but it takes time. "I've almost stopped being afraid of the police," he said. "But at least I'm aware it's just an unfounded fear, in contrast to Russia, where it's a completely founded fear."

Revin knew he was "different" from an early age, but he didn't know the word "homosexual" until he was 11, when the Russian news media reported on the U.S. military's "don't ask, don't tell" policy. A child of the upheavals of the late 1980s and early 1990s, he was always interested in politics.

After high school, he stumbled on the personals section of a local newspaper and opened a post office box to correspond with other gay men. At first he hid this from his parents, who work in a factory and have a traditional, Soviet-style mind-set about sexuality. By 22, he had moved out of their apartment and told them his roommate was actually his boyfriend.

Revin didn't conceal his sexual orientation in Russia, but there were limits. He held hands in public with a man in his hometown only once, at 18, in an act of alcohol-fueled bravado he now considers a bit childish.

His parents and his sister don't know that at age 27, Revin learned he was HIV positive. The status carries heavy stigma in Russia, and until recently it could have ruled out asylum in the U.S. A 1987 amendment advanced by Sen. Jesse Helms, who called gay people "weak, morally sick wretches," prohibited nearly all HIV-positive foreigners from entering the U.S. The ban remained in effect until 2010.

Like the dissidents and refuseniks of earlier eras, Revin thinks a lot about people back home. Some days he spends hours on Facebook and Skype, chatting with friends in the Russian activist community, helping them find contacts and contributing to projects like Children-404, a sort of "It Gets Better" collection of stories from LGBT Russian youth.

His advice for LGBT teens in Russia: Study a foreign language and be prepared to leave.

"It's much better when a person can plan his departure ... than to run away with one suitcase like I did," he said.

Revin hopes to learn enough English to go back to school and get a degree in social work, maybe from Georgetown. He believes that by the time he completes his studies, a sizable community of Russian-speaking LGBT émigrés will need support. In addition to the everyday challenges of immigrant life, some may face serious health concerns.

According to UNAIDS, rates of new HIV infection continue to rise in Russia and neighboring countries, even as they have dipped in most other parts of the world. A Russian government source told The Moscow Times that one in every 20 Russian men in his thirties is HIV positive. The virus is especially prevalent among men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who inject drugs. Stigma keeps many Russians of all sexual orientations from getting tested.

"I know some gay people who discovered they are HIV positive after arriving in the U.S.," Revin said. "It's like a double shock because there is nobody to share it with."

Revin already knows 10 other Russian LGBT asylum seekers who've arrived in D.C. since he did. He often serves as an informal advisor, suggesting where to take English classes, how to get translated documents verified, and where those who need HIV treatment can find it.

But before these new arrivals can really think about the future, they must prove to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services that they cannot return home. From preparing the asylum application to receiving a final decision, the process can drag on for months.

The U.S. has considered persecution for one's sexual orientation as a basis for asylum since 1994, but USCIS does not keep statistics on applications from LGBT individuals. Applicants must demonstrate that they have experienced past persecution or have what the government deems a "well-founded fear" of future persecution due to their LGBT status.

In 2011, President Obama issued a directive to government agencies to protect vulnerable LGBT asylum seekers and refugees. USCIS considers media reports and information from groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International when reviewing asylum cases. But while Soviet Jews were treated as a group and did not have to prove they had personally experienced anti-Semitism, LGBT asylum applications are evaluated on an individual basis.

Larry Poltavtsev, president of Spectrum Human Rights Alliance, a Virginia-based organization working on LGBT issues in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, hopes to change that. Poltavtsev said Spectrum has reached out to the State Department and members of Congress to lobby for Russian LGBT people to receive automatic refugee status. This would smooth their transition by allowing them to work immediately upon arrival in the U.S. But the lack of data available on Russia's LGBT population is a stumbling block, Poltavtsev said, making it difficult for officials to project how many people would seek refugee status if the option became available.

Revin is currently waiting for USCIS to schedule his interview with the local asylum office, the last step in presenting his case to the government. He has exhausted his savings and cannot work legally. He's a perpetual houseguest, put up by volunteers, and gets by with financial assistance from Center Global, Spectrum Human Rights Alliance, and some friends.

Despite the difficulties of starting over, Revin often finds himself marveling at the relative freedom LGBT people enjoy in his adopted city. On a sunny afternoon last October, he strolled through Dupont Circle, along the stretch of 17th Street named after the late gay rights activist Frank Kameny. Just up the street from Annie's, a joint that calls itself D.C.'s Gayest Neighborhood Steakhouse, two attractive young men in jeans stood on the corner. One of the guys leaned back against the electrical box. His partner grinned and drew him close for a kiss.

"Nobody cares," Revin said. "It's cool."