2016 was the year Black Lives Matter went truly global.

The US-born movement has spread as far as Brazil, South Africa, and Australia, where activists have taken to the streets and social media in solidarity with the victims of police killings. They’ve adopted the “Black Lives Matter” rallying cry to amplify homegrown movements and calls for racial justice — and used it to point out what they say is a hypocritical approach by the media and power structures in their countries.

“French media are able to see colors in other countries and write in a story headline that a black person was killed by the police in the US, but they are not able to do that in France,” Fania Noël, the coordinator of Black Lives Matter France, told BuzzFeed News.

International connections between civil rights and anti-colonialist movements aren’t new. But as a global phenomenon, BLM and offshoots like Native Lives Matter have fueled momentum and helped smaller groups connect and be heard. US organizers are approaching their work with a global lens. The policy platform developed by the Movement for Black Lives has been translated into Spanish, French, Arabic, and Chinese, and endorsed by Canadian activists who see it as a model.

BuzzFeed News spoke with activists in France, Brazil, Australia, Canada, the UK, the US, and South Africa on the issues local Black Lives Matter activists are focusing on, how they’re working together and how they see the future of organizing amid the global rise of far-right white nationalism.

PARIS — In July, hundreds of people took to the streets of Paris and Beaumont-sur-Oise to protest the death in police custody of Adama Traoré, a 24-year-old black man. The hashtag #JusticePourAdama — Justice for Adama — was quickly followed by #BLMFrance and rallies where protesters chanted “Black lives matter!” in English.

A new movement, Black Lives Matter France, was born, starting a conversation about race in a country that has long struggled to come to terms with its colonialist past and has since styled itself as a post-racial, colorblind republic. The slogan brought several existing groups working for racial justice and against police brutality together in a loosely organized coalition that aims to bring increased visibility to their causes.

BLACK LIVES MATTER #BLMFrance

“When we started the hashtag on social media, we wanted to also denounce the hypocrisy in France,” said Noël, the French Black Lives Matter coordinator whose group focuses on all forms of structural racism. “French media are able to see colors in other countries and write in a story headline that a black person was killed by the police in the US, but they are not able to do that in France.”

Other groups have also sought to learn from BLM, including Urgence Notre Police Assassine, France’s main organization against police violence, whose name translates roughly to “Emergency, our police are killing.” They don’t explicitly focus on race as an issue in police killings, but have also been in contact with BLM in the US, helping to prep a July visit for Evelyn Reynolds, a BLM activist from Illinois who reached out by email before heading overseas.

“French media are able to see colors in other countries and write in a story headline that a black person was killed by the police in the US, but they are not able to do that in France.”

“We met to see how similar our work is, talk about what we live day after day,” said Amal Bentounsi, who created Urgence Notre Police Assassine after her brother was killed by police in 2012. "It's really hard and I'm not really organized. I need to learn from them. I wasn't born an activist, I need to be inspired by them and also to bring them what we know how to do.” Bentounsi plans to launch an online “observatory of police violence” that will track victims and share additional data on the topic.

Groups in the BLM France coalition have participated in protests against police violence and in support of Adama Traore’s family. In November, they organized an action in Saint-Denis, a suburb to the northeast of Paris, after an altercation at a train station there between the police and a white university professor who was filming the arrest of a black woman.

With France’s own presidential election coming up this spring, there has been much talk of Donald Trump’s victory as a boon for far-right parties around the world. But Noël doesn’t see his win, or French politics, as having much influence on her work.

“These sorts of events will mostly have an impact on people who want to join movements such as 'All United Against Hate' [a government campaign against racism], not ours,” she told BuzzFeed News. “They won’t turn to organizations that want the end of white supremacy.”

—David Perrotin and Cecile Dehesdin, BuzzFeed News reporters, France

SÃO PAULO — As the world’s attention turned to the Olympics in Brazil this summer, a delegation of US Black Lives Matter activists visited Rio de Janeiro in July to meet with local groups working against racialized and police violence.

It was an emotional trip for Rev. Waltrina Middleton, a Cleveland-based social justice activist. Her cousin, Rev. DePayne Middleton, was one of nine black Americans killed when a white supremacist opened fire during bible study at the historical black Emanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, last year.

In Rio, Middleton met Débora Maria da Silva, who lost her son Edson to the deadly wave of violence that shocked São Paulo in May 2006, when the authorities lashed out after a gang uprising. In just two weeks, hundreds of civilians died in what human rights groups say were often execution-style police killings targeting poor young people of color. Da Silva believes Edson, then 29, was shot by a death squad made up of police officers while he was on his way home from her house.

Middleton marched silently with da Silva and other Brazilian mothers through one of the favelas where their children had been killed. The women had been denied a platform to speak to the authorities, but refused to be ignored, carrying photos of their slain children past police checkpoints.

“We have to be the authors of our own narrative and that’s what these women did,” Middleton told BuzzFeed News. “To see these women hold space — occupy spaces and declare it sacred in the name of their deceased and murdered child — that’s powerful.”

Thousands killed by police in Río and São Paulo each year #BLMinBrazil #BlackLivesMatter

The US delegation asked for a flag from da Silva’s group, Mães de Maio, which translates to "Mothers of May,” to take home, “and it is as if they had taken our kids with them,” she told BuzzFeed News.

"The bullet that kills there is the same that kills here,” da Silva said of police killings in the US and Brazil. “The police officers are acquitted in both countries.”

Ten years after Edson’s killing, not much has changed. A 2016 report by Amnesty International outlines a disturbing number of extrajudicial killings in Rio de Janeiro and cover-ups by a police force rarely held to account. Black and mixed-race Brazilians outnumber whites, but lag behind in income, educational attainment, and representation in the government. A recent parliamentary inquiry found that a black youth is murdered in Brazil every 23 minutes.

The Brazilian mothers have stayed in touch with the Americans they met and connected online with activists from El Salvador, Canada, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico. They plan to meet again in Rio this May.

Middleton says global relationships help sustain her activism in the US. “As soon as Donald Trump was elected, I was flooded with messages saying ‘We’re here for you, we love you,’” she told BuzzFeed News, noting that even if Hillary Clinton had been elected, her work would not have been easy.

In resisting the racist rhetoric and ideals that swept Trump to victory, Middleton says American activists have to look beyond the US.

“We have a responsibility to be conscious and concerned about its impact in the diaspora and in the world,” she said. “We can’t afford to look away.”

—Tatiana Farah, BuzzFeed News reporter, Brazil and Susie Armitage, BuzzFeed global managing editor

LONDON — Some British activists see a wider remit for the Black Lives Matter movement post-Brexit, which has seen hate crimes, anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiments on the rise.

“When you say ‘black lives matter’ we don’t just mean ‘black British citizens’ lives matter,” said Alexandra Kelbert, a 25-year-old teacher and researcher who is part of a network of activists using the name Black Lives Matter UK. "We’re also thinking about the Immigration Act which is making it impossible for a lot of people, including a lot of black people, from being able to work, rent, and just have a life in this country.”

Campaigning for broader issues under the BLM UK mantle hasn’t always gone over well, however. The group faced a barrage of criticism in early September after holding a climate change protest at London City Airport featuring nine activists who were all white. Kelbert, who is black, said the decision to deploy an all-white crew was a “strategic but necessary” one, though many didn’t buy that, or BLM UK’s framing of climate change as a “racist crisis.”

The UK is the biggest per-capita contributor to temperature change & among the least vulnerable to its affects.

Discussions about state violence, racism, and the various ways black people are oppressed are not new to Britain. Most British law enforcement officers do not carry guns, but a disproportionate number of people from black and other ethnic-minority backgrounds, often with mental health problems, die in police custody following the use of force. Groups such as Inquest and the United Families and Friends Campaign have been working for decades to seek justice for and support those who’ve lost loved ones in custody.

Victims’ relatives often spend years pressing for answers. An investigation four years after the death of Kingsley Burrell, a 29-year-old black man who died in 2011, found the cause to be neglect and prolonged restraint by Birmingham police. Black Lives Matter activists in the US and the UK have bolstered the Burrell family’s long campaign for justice, and in October, three officers were charged with perjury in the case.

"Anti-blackness is not an America-specific phenomenon — it's global."

Protesters remembered Burrell days after the July shooting of Alton Sterling at a Birmingham march that drew more than a thousand people. Similar rallies took place across the UK to show solidarity with US victims of police violence and draw attention to similar cases in Britain. Local Black Lives Matter groups, which are not officially affiliated with the US organization, have formed in London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Nottingham, and Manchester.

“I think that people who may have been having those very conversations for a long time now have been galvanised, and have been brought together under this one line,” Kelbert told BuzzFeed News. “[The US Black Lives Matter network] see us and we see them, and we’re building.”

“We should be talking about anti-blackness in our own context because anti-blackness is not an America-specific phenomenon — it’s global,” said Imani Robinson, a 24-year-old from London who is also part of the BLM UK network.

—Fiona Rutherford and Victoria Sanusi, BuzzFeed News Reporters, UK

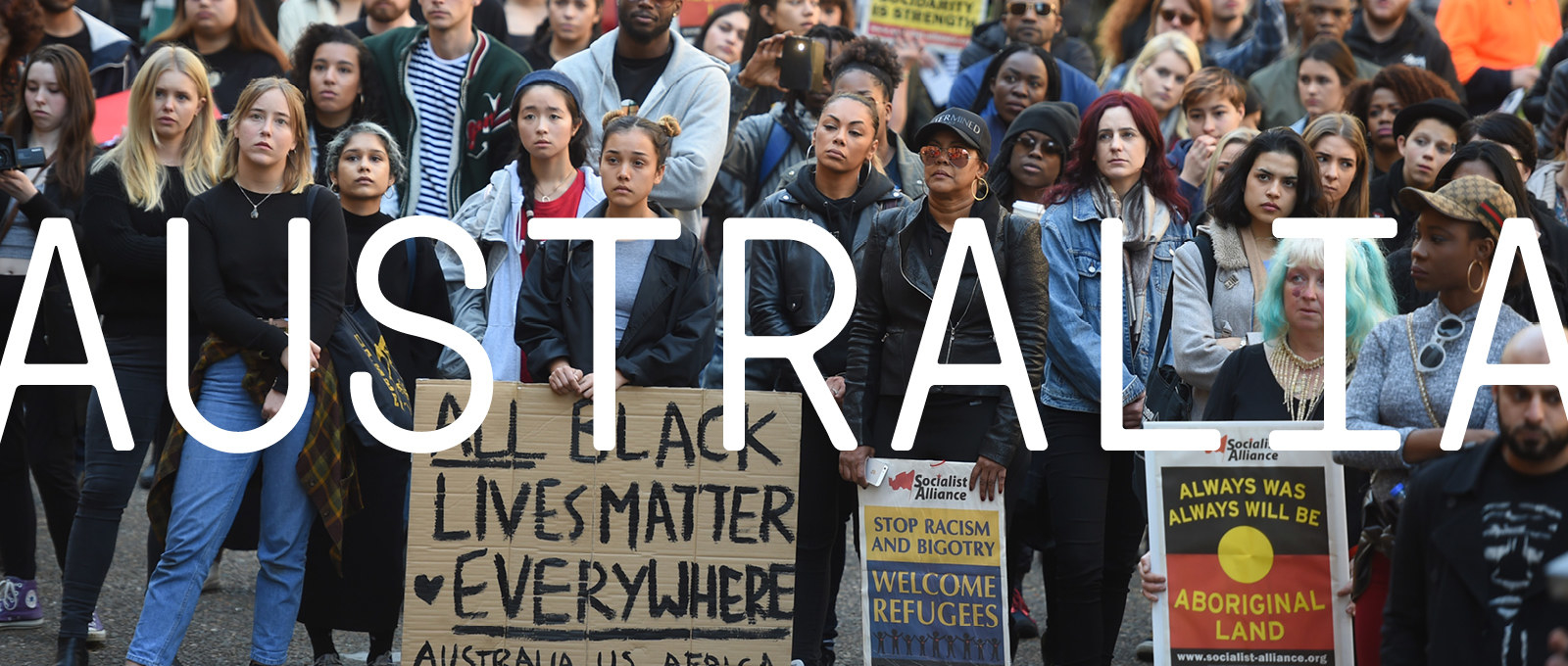

SYDNEY — “A lot of us activists here would love to be at Standing Rock,” Shaun Harris, an Aboriginal man from Western Australia, told BuzzFeed News, referring to the Native American–led protests against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In a year when typically little-covered Native issues lit up Facebook feeds and the killings of black Americans by police made international news, Indigenous people in Australia are pushing for the violence inflicted on their communities to get similar attention.

“What is happening in America is exactly what is happening here,” said Harris, whose 22-year-old niece died in police custody in 2014. When he heard about Black Lives Matter last March, “it was like a yes moment, thinking this is what we need here in Australia.”

"A lot of us activists here would love to be at Standing Rock."

Harris’s niece, who is identified as Ms. Dhu in accordance with the Western Australian Yamatji tribe’s tradition of not using a deceased person’s first name, was jailed in 2014 over unpaid fines. She died from an infection in custody 48 hours later. Dhu had repeatedly told doctors she didn’t feel well, but was dismissed as having “behavioral issues.” Her family is lobbying the authorities to have the CCTV footage of her death released to the public.

Though Aboriginal Australians have long drawn inspiration from the black American struggle — in the 1970s, a small group even formed a local offshoot of the Black Panther Party — online movements like Black Lives Matter, Native Lives Matter, and Aboriginal Lives Matter have given them a way to connect directly with other Indigenous people and join one another’s uprisings.

In July, Harris told his niece’s story at a Black Lives Matter rally in Perth. In October, activists with the Grand Central Crew held a solidarity march in New York for the family’s campaign.

Last night, #PeoplesMonday shut down NYC for #MsDhu, a native woman killed by Australian police (pics: @KeeganNYC)

Harris credits Black Lives Matter with amplifying the family’s call to make the footage public. Western Australia’s premier — a role akin to governor in the US — has said he sees no issues with releasing it, and two senators have proposed a motion in the Australian parliament to compel the local authorities to do so.

The state’s treatment of people like Ms. Dhu lies at the heart of Australia’s Black Lives Matter movement.

Twenty-five years after a royal commission recognized widespread institutionalized racism in Australia’s justice system, Indigenous Australians, a group that includes Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, continue to die in police custody at high rates. Since the period covered by the report, close to 400 black people in Australia have died in police or prison custody. Indigenous people make up 27% of the incarcerated population compared to just 3% of the country’s population overall. In the Northern Territory and Western Australia, the figure is over 80%.

Aboriginal elder and veteran activist Ken Canning told BuzzFeed News, “While [the police] are not putting bullets in black people’s heads in the street, they are murdering them behind closed doors.”

—Allan Clarke, BuzzFeed News Indigenous affairs reporter, Australia

DAKAR, Senegal — Eight thousand miles across the Atlantic Ocean from Louisiana, South African activist Wandile Kasibe heard the news of Alton Sterling’s shooting and felt a familiar sinking feeling. A day later, the death of Philando Castile in Minnesota drove him to action in Cape Town, the scene of some of the country’s own starkest segregation. There Kasibe organized one of dozens of smaller stand-ins and marches that have rippled across Africa on the same tidal force as those in the US.

“When we responded to the killings that had taken place in the US, it’s because we get what’s happening there,” he told BuzzFeed News. Before the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1994, scenes of white law enforcement officials shooting black men were commonplace.

When Kasibe led a group of unarmed protesters to the US Consulate in Cape Town in July, the police stood ready to shoot. “We see what they’re doing in the US, and we saw what they did in Marikana,” he said, referring to the 2012 massacre when 43 striking miners were shot dead, most in the back as they tried to flee.

Citizens across the continent have drawn parallels and inspiration in dealing with local surges in police brutality, while a spin on the hashtag has seen a call in Uganda for an “African Lives Matter” movement to tackle social ills at home.

While race doesn’t play the same role in most African countries as it does in the US, with South Africa as a notable exception, activists recognize the same privilege and power that leads to police impunity overseas. Inspired by the graphic streams capturing the killings of black Americans, Africans are increasingly posting videos of police abuse online. In at least recent two cases in Ivory Coast and Guinea, the recordings have gone viral and some officials involved have been suspended — rare occurrences in both West African nations.

Black Lives Matter has rekindled a connection between Africans and the black diaspora in the 1960s, when the US civil rights movement resonated among nations shaking off the shackles of colonialism. But #AfricanLivesMatter has also been a remainder of the West’s lack of corresponding solidarity — including by black Americans — when it comes to the continent’s tragedies. That ranges from the relative indifference to the plight of Africans caught up in Europe’s migrant crisis, to greater concern for Barack Obama’s safety during a visit to Kenya than for the 147 victims gunned down there during an April 2015 terrorist attack.

Students and workers march through the streets of Braamfontein. We are marching against the police brutality… https://t.co/Q15skIA8j5

In South Africa, other recent student movements predate the local connection with Black Lives Matter but share its focus on racial justice. Last year, #RhodesMustFall protesters called for a statue of 19th-century British white supremacist Cecil Rhodes to be removed from the University of Cape Town campus. The call to “decolonize” South Africa’s once whites-only campuses then grew into the #FeesMustFall campaign, sparked by universities’ attempts to increase tuition fees in a country where black households still earn six times less than white ones.

—Monica Mark, BuzzFeed News West Africa correspondent

TORONTO — The Black Lives Matter movement here is challenging the idea that the country, where around 3% of the population is black and 4% Indigenous, is a progressive paradise.

“As a group, we're often told that racism ‘doesn't exist’ in Canada like it does in the States,” Black Lives Matter Vancouver organizers told BuzzFeed News in a statement. “This is exactly the problem. Canada is inherently racist. It is a state built on colonization and the continued oppression and disenfranchisement of Indigenous people.”

Canadian activists saw an opportunity in the outrage after a grand jury declined to indict Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson over the shooting of Michael Brown. Jermaine Carby, a 33-year-old black man, had been shot by police just two months before during a routine traffic stop in Brampton, a suburb of Toronto. Black people were also disproportionately affected by carding, a stop-and-frisk-type program used by the Toronto police.

"We're often told racism 'doesn't exist' in Canada like it does in the States."

“We recognized that something needed to happen and we really saw momentum happening in the United States,” janaya khan, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto, who styles their name in lowercase and uses gender-neutral pronouns, told BuzzFeed News.

The group organized its first protest that month, then reached out to Patrisse Cullors, an LA-based co-founder of Black Lives Matter, and eventually became an official chapter of the US organization. After the shooting of Andrew Loku in July 2015, BLM Toronto contacted activists in Vancouver to start a second Canadian group there.

The Toronto chapter has a close ties to Indigenous activists and khan credits the indigenous Idle No More movement, which started in 2012, with bringing a “radicalism” to Toronto that made Black Lives Matter possible. A 2015 retreat for BLM chapters in Detroit was also hugely influential for khan.

Fighting for Jermaine. Fighting for Abdirahman. Fighting for Andrew. Fighting for black lives to matter here, in Ca… https://t.co/xkzuRstYHV

“We were working and operating in what felt like a lot of isolation,” they said. “So to connect with the larger movement, with people who believe in black life and black equality of life, it was transformative, it was life-changing, it was necessary.”

A personal relationship flourished as well — Cullors and khan have since married.

In the two years of its existence, BLM Toronto has become a visible presence in the city, and the US and Canadian chapters have shared tactics. A 15-day “tent city” outside Toronto police headquarters was directly inspired by a visit to an occupation in Minneapolis protesting the death of Jamar Clark, and also served as a model for BLM’s occupation of LA City Hall.

Going forward in the face of a Trump presidency, khan sees BLM looking to build more relationships with other activist groups, particularly those focused on environmental justice.“I think we’re going to see Black Lives Matter infiltrate many, many different movements in the hopes of building solidarity,” they said. “Local grassroots models, we deeply believe, are what’s going to change things.”

—Lauren Strapagiel and Ishmael Daro, BuzzFeed News reporters, Canada

WASHINGTON, DC — Activists inside the movement commonly referred to as Black Lives Matter — an accomplished, diffuse, and politically malleable movement made up of formal groups and nontraditional hierarchal leadership — point to different anecdotes marking when and how the movement went global.

Some refer to a particular tactic or safety tip from someone abroad. For others, it was an email or direct message with a message of solidarity or encouragement. Many took trips abroad or gave advice to young protesters in places like the UK, Toronto, or Paris. But two maps show in 2014, news and activism that followed Ferguson and with the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter, as well as #HandsUpDontShoot and #ICantBreathe, exploded as a global protest movement and social media phenomenon.

As the events made front-page news around the world and police teargassed people protesting the killing of Mike Brown, Palestinian activists, no stranger to being teargassed themselves, used social media to send the demonstrators advice.

Always make sure to run against the wind /to keep calm when you're teargassed, the pain will pass, don't rub your eyes! #Ferguson Solidarity

That summer, as the police and protesters clashed in Ferguson, Israeli forces killed 2,220 Palestinians during the war in Gaza, including nearly 1,500 civilians. “The chemicals that were used in Gaza were manufactured in the US,” Umi Selah, an organizer with the social justice group Dream Defenders, told BuzzFeed News. “So I think that was a very explicit moment where the importance of solidarity became very clear and that while our struggles aren't exactly the same, we are definitely fighting against the same systems.”

The global protests taking place under the Black Lives Matter slogan have forced many US activists to look at America’s standing in the world, where they are seen as important figures in the movement for equality.

"We have a very particular sort of positionality as black protesters living in the belly of the best, living in the heart of empire."

“We can’t see our issues as just domestic issues,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Cullors said on the Laura Flanders Show. “We have to see how the US empire exports racism, how it exports militarization ... I think if I didn’t make those trips I wouldn’t have understood how necessary it is to call out for a global movement.”

For US Black Lives Matter activists, approaching their work with a global lens takes shape in actions like making sure T-shirts with radical movement slogans aren’t made in sweatshops, supporting the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign in Palestine and moving the conversation beyond Ferguson, police violence, and racism — to an international vision for defending human rights.

“We have a very particular sort of positionality as black protesters living in the belly of the beast, living in the heart of empire,” Rachel Gilmer, chief strategist of the Dream Defenders, told BuzzFeed News. “That means interrogating every aspect of our movement and in particular interrogating privileges that we hold as Americans.”

In the wake of Donald Trump’s victory, the Black Lives Matter organization called for renewed commitment to its mandate of ending state-sanctioned violence. “The work ahead will be just as much about the person occupying the Oval Office as the culture that got him there,” Brittany Packnett, a co-founder of Campaign Zero, a group working to eliminate police violence, told BuzzFeed News.

And yet, global connections continue to be a source of inspiration and encouragement for a movement that is gearing up for its biggest fight yet.

“Watching tactics, language and a shared vision for Black Lives being shared globally is beautiful,” Thenjiwe McHarris, an organizer with the Movement for Black Lives, told BuzzFeed News. “It reminds me in the most difficult moments that we will win.”

—Darren Sands, BuzzFeed News Reporter