Towards the end of Nitesh Tiwari’s Dangal, the film’s four screenwriters find an innovative way to ensure that Aamir Khan’s character doesn’t get to watch his oldest daughter Geeta Phogat clinch a gold medal at the 2010 Commonwealth Games in New Delhi.

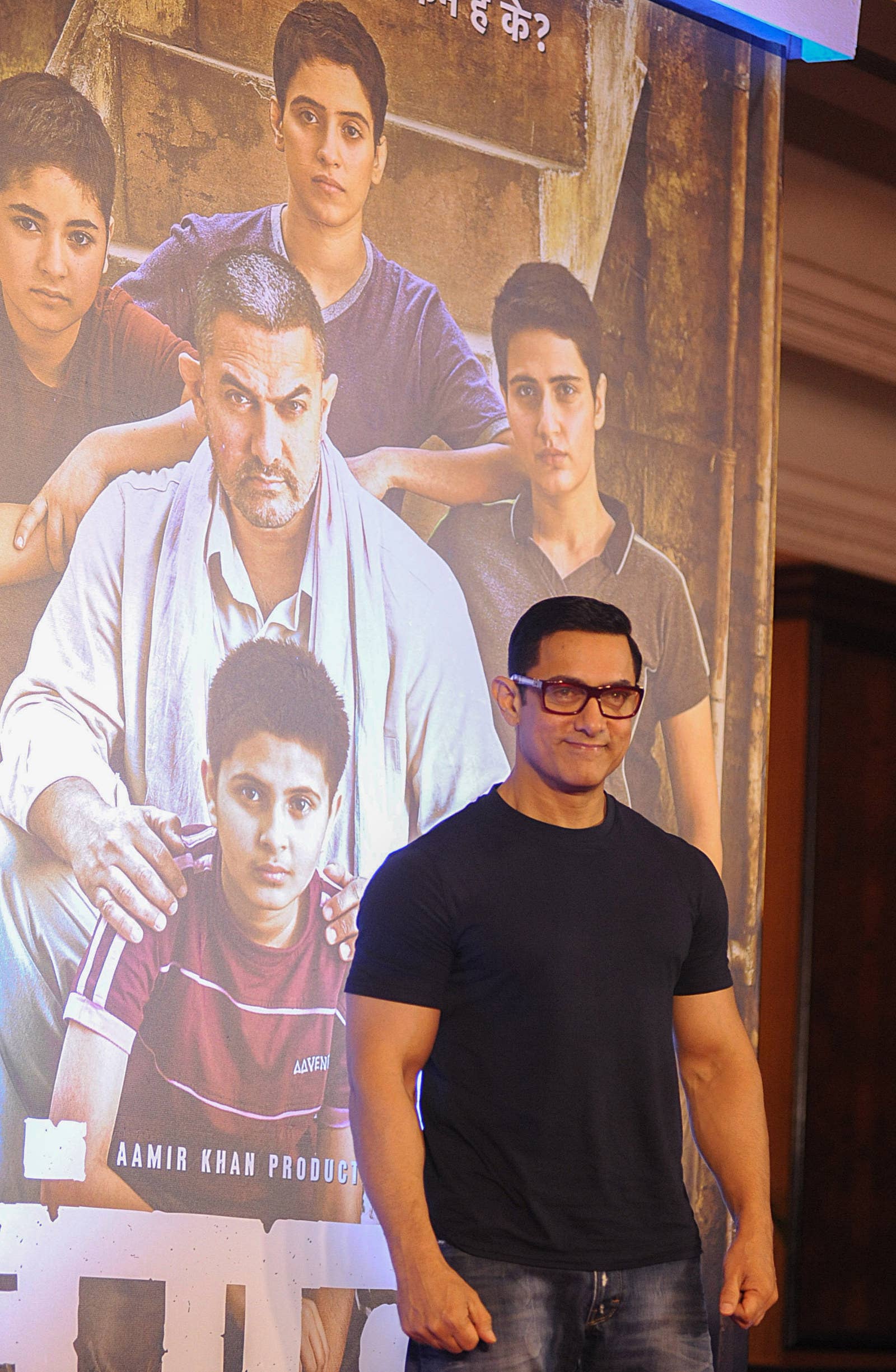

Khan is certainly the biggest draw of this film.

And so, though the triumphant moment and medal belongs to Geeta, there’s simultaneous focus on Khan too.

Which is no surprise, as Khan is certainly the biggest draw of this film. His much-publicised weight gain and subsequent loss have given the film a steady stream of press for the past two years.

And now, released to near universal critical acclaim, Dangal is being hailed as a "feminist film".

Its premise, on paper, is encouragingly progressive.

Dangal is being hailed as a "feminist film".

Mahavir Singh Phogat, a former National-level champion wrestler from a small village in uber-patriarchal Haryana, realises that his daughters are capable of wrestling after they display a very ‘masculine’ trait: reacting to an unfavourable situation with violence.

He then defies all odds and trains them to be world-beating wrestlers.

The fact that most of this story is set in a state notorious for gender inequality, including some of the highest incidences of female foeticide in the country, makes one root for the girls that much more fervently.

Logically, though, a truly feminist film on such a subject would have treated Geeta Phogat as the protagonist and Mahavir as a strong supporting role.

Dangal does the opposite.

A truly feminist film would have treated Geeta Phogat as the protagonist.

It’s celebratory tone overlooks the borderline abusive mentor-student relationship between Mahavir and his two oldest daughters, and there’s no true depiction of what it’s like to have your girlhood snatched away in pursuit of your father’s dream.

We also see how the girls are made to shun all signs of femininity in order to become good wrestlers.

Perhaps the most egregious example of the film’s dogged need to promote masculinity — and I mean "masculinity" as the toxic social construct that promotes dominance and rejects everything "feminine" — as a prerequisite to sporting excellence is a plot element that involves the length of Geeta’s hair.

At first subtly and later overtly, the movie links Geeta reclaiming her femininity – watching Dilwale Dulhania Le Jaayenge for the first time, craving attention from boys, painting her nails, growing her hair long – to a dip in her form.

The movie links Geeta reclaiming her femininity to a dip in her form.

The visuals are juxtaposed against those of Babita Kumari, Geeta’s sister, still with short hair and following all of their father’s rules.

After an epiphany that her father – rather, Aamir Khan – was right all along, she is quick to shear those locks off, signalling a return to her older ways.

Interestingly, the real Geeta Phogat has sported long hair for many years – even when she won her first gold medal at the 2010 Commonwealth Games.

Dangal doesn’t strike me so much as a feminist film as much as one that uses feminism as a plot device: to give its ‘hero’ a cause to fight for.

This better-educated cousin of the industry seems to have found a middle path

In Aamir Khan’s brand of cinema, which usually features him as a one-indignant-man-against-the-world hero, there are several such devices: from dyslexia in Taare Zameen Par (2007) to religious intolerance in PK (2014).

It isn’t just Khan, though, and what we see in Dangal has perhaps become a pattern in films classified as so-called ‘new Bollywood’ aka ‘content-driven cinema’.

This leaner, better-educated cousin of the industry that still makes gay jokes (see: Kyaa Kool Hain Hum 3, Mastizaade, Housefull 3) seems to have found a middle path: one where progressive concepts like feminism, mental health, and consent are discussed, dissected, and hung out to dry while still luring audiences into theatres with the usual trappings – A-list stars, preferably male; songs, even if out of place; and a slightly larger-than-life approach to direction and production design.

With this approach, you get a broad, palatable gender-role-"reversal" movie like R. Balki’s Ki & Ka (2016), which should’ve really tried to say ‘Everything is everyone’s job and nothing is any one person’s job’ but ends up saying “A man can do a woman’s job and vice versa and there’s nothing wrong with either”.

Why couldn’t the girls in Pink have hired a female lawyer?

Or you get the much-hailed courtroom drama Pink (2016), where Amitabh Bachchan, a retired lawyer, is hired by three women accused of attempted murder. The movie makes powerful, if unsubtle, points about consent and double standards for men and women. It also builds up interesting female characters only to have them saved by a man.

The audience gets the following message: these women had their moment in the sun; now it’s time for a man to come and finish the job.

Why couldn’t the girls have hired a female lawyer? Because no one wants to watch that movie.

Just as no one, apparently, wants to watch a Dear Zindagi if Alia Bhatt’s therapist isn’t a grizzly-sexual Shah Rukh Khan in pastel-shaded linen shirts.

In that film, Bhatt plays an attractive, intelligent cinematographer in her early 20s who has to look patiently puzzled while Khan’s impossibly charming Dr. Jehangir Khan compares looking for a romantic partner with chair-shopping.

Please tell me that scene made you groan out loud too.

Why are some Bollywood films unwilling to go all the way when it comes to equipping female characters with agency?

I think it comes from a place of mild-but-not-willful ignorance; the persistence of the star system heavily tilted in favour of male actors; and a notion that the paying audience will only tolerate so much subversion.

There have also been Hindi films,that have created satisfactorily feminist scenarios.

But there have also been Hindi films, especially in the recent past, that have created satisfactorily feminist scenarios without sacrificing context and believability.

In Sharat Katariya’s Dum Laga Ke Haisha (2015), Bhumi Pednekar’s Sandhya shows us that a schoolteacher in 1990s Haridwar needn’t put up with her husband’s unsavoury comments about her appearance.

In Ashwini Iyer Tiwari’s Nil Battey Sannata (2016), Swara Bhaskar’s Chanda doesn’t need a man in her life to doggedly inspire her teenaged daughter to do better in school.

In Pavan Kirpalani’s Phobia (2016), Radhika Apte’s Mehak has to deal with severe and sudden agoraphobia all by herself—her friend Shaan (Satyadeep Mishra) tries hard to be her saviour, but her journey to clarity is self-scripted.

None of this is to knock down the positive, progressive ideals that mainstream films like Dangal, Pink, and Dear Zindagi promote, of course—it’s important to remember their reach and impact.

We tend to approach Bollywood with kid-gloves

We tend to approach Bollywood with kid-gloves when it comes to such things, going out of our way to appreciate good intentions and broader statements.

But intersectional feminism is complex and multi-layered, and mainstream cinema lays emphasis on simplicity and emotional manipulation.

This, as you can imagine, isn’t an ideal mix.

When we call a film ‘feminist’, it is important to examine it from every angle possible.

When we call a film "feminist", it is important to examine it from every angle possible.

To me, it seems that Bollywood is caught in (irony intended) no man’s land: a certain set of new filmmaking voices are eager to tell progressive stories, but are – intentionally or not – unable to break free of economics, which unfortunately relies to a large extent on a male-actor-dominated star system.

As films like Dangal, which is well on its way to becoming the biggest hit of the year, are celebrated for their progressiveness, it is just as important to highlight all the ways they didn’t succeed.