When you were young you used to be immaculate. Immaculate. The house, the carpet, walls could be a mess, but never you. She’d plonk you in a bath. You’d kick your chubby legs, and watch them pinken. She’d clean you and she’d sing to you and tell you little stories so you wouldn’t be afraid to be submerged. To be so close to drowning and not drown. Women such as we, your mother told you, we feel things strongly and we always have. You need to choose to love, and love, not hate. Be gentle and be kind and be my daughter.

You say that to yourself these days. A lot. Words are not truths. Your father said he loved you. He didn’t, though. Not after she was gone. And there you were, alone inside a house. He’d go on business and he’d shut the door. You learned to feed yourself. To tidy up. To manage and make do till he came home.

When he returned, he’d open up the door, and you’d approach. Eagerly, with smiles, the first few times. Then slowly, like a dog that knows that legs are built to kick.

He’d look through you. You’d cook him dinner and he’d chew the food. He’d look through you. You’d go to bed and it would be the same as when she vanished. You have been lonely since your mother died. She loved you. And she died. The love he had for you was just a product of his love for her and when that died some of him died as well.

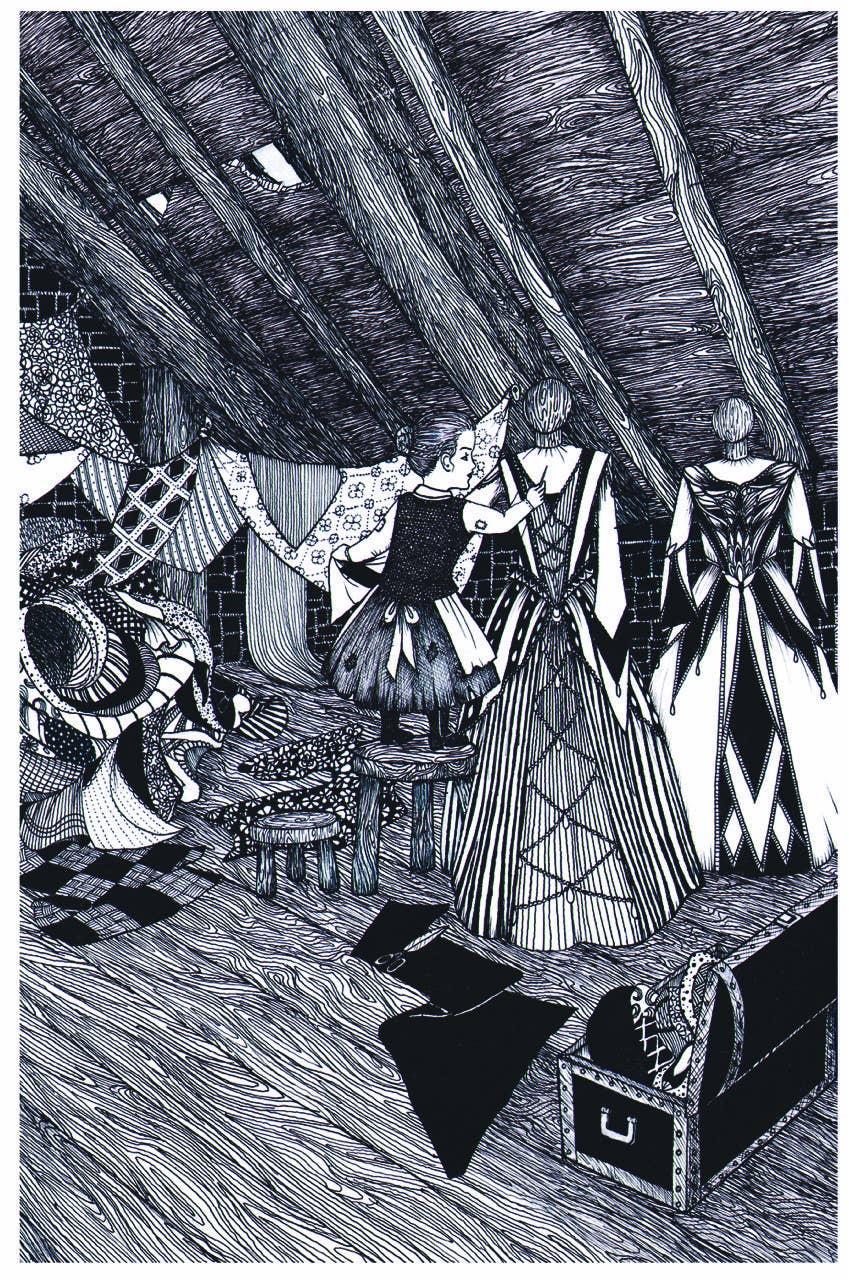

You have her clothes. You keep them in the attic. They are lovely. Sometimes you catch her scent upon the air. A soft and dusty flutter. It eats at you, like moths upon a cloak.

It’s hard to have a house all by yourself. But it is easier than the alternative. When he comes home with her you close your eyes. He holds her hand. They are already married. Her daughters, two tight replicas, are scowling. She lets them be. You’re not a thing that matters. Part of the house. A chair. A spoon. A plate.

They need your room for one of her two daughters. You start to sleep upstairs beside the clothes. You build a pile of rags, all bunched together. Little birds make nests to live in. And you are small. You come up to their waists.

You are a woman. You are a woman the size of a child. They treat you like a thing. They talk about you when you’re in the room. The only way they look at you is down. It must be hard they say. To be that way. They mean the way that you have been for ever. And you are just a girl inside a house.

Your mother shaped like you. Your father loved her. It is things like this that get you through. Your back hurts, scrubbing floors and hemming gowns. Your sisters (they are not your proper sisters) talk about the future, marriage, babies, gowns and balls and things that they will buy with all their wealth. Their dreams are tall rich men to do their bidding, whose arms are made of heavy golden coins. To wrap around their bodies, keep them safe. Money can be armour, if you have it.

You mop. You break the sticks. Stand on little stools to stir the pot. Sometimes when they remember you are there, they talk about you. Your life was ruined as soon as you came out, they tell you. They bet that you were cute, though, as a baby. When you were meant to be a little thing. And was it easier, then, for your mother, did you just plop right out, as though an egg?

You kill a chicken for the dinner, gut it. Stuff it tight with herbs, delicious paste. The blood collects and mingles with the feathers. The viscous dribble of the shell-less eggs. Every life is full of possibility, you think. And there are other places you can go.

The ash dulls in the hearth. Waiting to be gathered and scooped out. They let it die right down, and chide you for it. You’re a servant now. Only you don’t go home to the village at night. You do not sleep in a warm feather-bed beside your husband. You do not kiss your children’s faces. You hold your mother’s love inside your mind. Be gentle and be kind and be my daughter. It hurts you now. A razor and a prayer.

Years pass, and you assume a woman’s shape. You are lovely. Your eyes are wide, your skin is smooth and whole. Your limbs are shapely, smaller than they should be, but still pleasing. You like your legs that take you different places. You like your arms that make things, grow things, mend.

The invitation comes to the door with pomp. A footman, short and pigeon-chested, stomps into the hall and proclaims the words. And like a magic spell, the house begins to swirl. Before all this, they lived in stasis. Now you hear the hum of their demands all day and night. Hem this and affix crystals onto that. The furniture gathers webs and dust as everyone turns to work, real work. The kind that turns a woman to a wife. A simple village girl into a princess. You chuckle in your nest at the idea. You run your hands across your mother’s silks. Her satins, velvets, lace. The textures and the vivid shades she liked.

He gave her more than he has given them. He loved her more, you think. He loved her more. A small daguerreotype of her kind face, hair a rippling river down her back, is wrapped up tight. A secret in pink leather. You keep it at the bottom of a trunk and only look sometimes. You don’t want to remember the stiff formality of someone still. Your mother liked to move. And she was colours. Colours and a voice. And you were loved.

You make candles from stubs of other candles. You like light in your room to look and read. Gillian wants thick, warm, yellow fabric, soft as butter. Lila prefers cold. All icy blues. Their dresses made to measure. No expense spared. And dancing slippers. One night’s wear and out the door like ash. You can’t even borrow their cast-offs. You wear a pair of boots got from a child. Of sturdy stuff, that keeps the water out and gets you round. Your mother’s slippers have little bits of mirror on the toe and they are velvet. She wore that pair the most. You can see the little curve her toes made on the inside. The weight of her. It has a certain power.

Your father is away all of the time now. Even when he’s home, he isn’t there. At sea, he gains and loses things. Cloth and jewels and spices. Brightly coloured things that tease the eyes. You think about the soft crash, wave on shore. How dangerous the journey out would feel. How wide the possibility. Potential for the lives you could try on. This house, this life, this village. They weigh you down; you’re covered up with ash and sunk in tar. You are a thing to comment on. Forget. You are a thing that makes this house a home with two small hands. And they don’t think on that, although they should. You brush your hair and braid it round your head. It’s not as long as hers, but it is thicker. There’s a sheen to it that pleases eyes. People like their women to be lovely. Women are a lot of different things.

Your stepmother’s face is very smooth and comely, till she opens up her mouth and screeches like a hawk for you to hasten. You comply. But you are not compliant. Your clever fingers weave a different plan. Rub oils into your aching muscles at the end of days. You’ll be a pretty, fragrant thing despite them. You don’t care what it takes. You know you’ll go. And you will not come back.

You sew the things that you will need in secret, slicing up the little bits of Mam. She was a little smaller round the waist, and you are taller now, but just a touch. The corset fits, but you are done with cages. Kohl around your eyes. The fire dies. You look into the mirror. Eyes that shine. Work harder than you have ever worked and be ignored and still retain your value. Do more than most and smile and be in pain. What breaks a person builds another person. Something strong is growing in your stead. A magpie’s nest. Old treasures. A new life.

The day arrives. They skitter round like insects. You brush them off and help them look the part. The sun goes down, and they alight the stairs, their faces painted whiter than their faces. Their breastbones dappled with the pink of strain. They are wearing emeralds and rubies. Ropes of things more lovely than their skin. Vases for their soft pink, plucked bodies. Tentative as deer, they step into the carriage, to the night. You can see the hope etched on their faces, hope and pressure. Not for you. Their world is not for you. Your father loved your mother. But he does not love you. You blink your eyes. They fill with tears. It stings. It melts the kohl. The ash streaks on your face.

You take a horse from the stables. You’ve gathered enough money for a while. You do not know what’s out there. What leaving will mean. But walls are not a home. No matter how familiar their appearance. You need to go. To get out. Need to go. Hair down your back, and gentlewoman’s clothes, and a fat black steed with mother’s special saddle. Ointment for your muscles. Blankets. Cloak. A fading picture of a sparkling woman. You hold her in your hand and in your heart.

The village lit with candles and with lanterns. You think of market day, parades of cows. And which is best? The juicy meat prepared for royal lips. For royal teeth and gullet. The cheaper cuts can nourish just as well. It all depends on taste. Safe passage in the night, away, away. You sleep inside the forest. Knife in hand, you curl in to the horse. Little things are easy to conceal.

Later, in an inn some leagues away, you look out at the castle. The view through unfamiliar panes is different. The stark shape of it on the distant hill. It’s fortified to keep the people safe, and it looks like a prison, thick and grey. The windows little slits for arrows to poke out. It must be dim, you think. It must be awful. Staying in one place. You know the weight. You count the coins secreted on your person. You have enough. Enough to get away. Enough to keep on moving till you find a place that’s worth the wait.

Stretching on the bed, with soft bread in your mouth, the taste of butter, you wonder what they’re doing at the ball. Who the prince will dance with. The love he’ll choose, the girls he will discard. There’s nothing gentle in that sort of power. You close your eyes. There is a different world. Where people do things, make things. Carve them out. You breathe the thick, soft air. It smells of hops. You smile and square your shoulders. Sometimes love is something more like rage. It makes you fight. You feel the future, wide and bright around you, kicking in your gut as though a child. The night spreads wide and you have flown, you’ve flown. The shape of you impressed in attic cloth is all that’s left. You wonder how long it will take for them to notice. It is an idle thought. You do not care.

You unclasp the bag that you have taken. Your hands delve deep through metal, paper, cloth. They prise the things you wanted from the others. Pull them, like a turnip, from the earth. And on the feather-bed, you plan your future.

You try on mother’s shoes. The slipper fits.

Tangleweed and Brine, by Deirdre Sullivan with illustrations by Karen Vaughan, is a new collection of reimagined fairy tales. The book full is out from Little Island now. Get a copy here.

BuzzFeed may collect a share of sales from this link.