In the Ohio River Valley, where breezes tend to stagnate, Louisville, Kentucky, has long struggled with its dirty air. The region is among the top 15 areas in the United States with the worst particle pollution, thanks to industrial and vehicle emissions. Just this week, it was once again given a failing grade for ozone pollution by the American Lung Association.

Until recently, Louisville residents had few ways of measuring the quality of the air outside their own windows. Traditional, stationary air quality monitors operated by the federal and local government can only measure air on a regional scale. And the breadth of such measurements often masks the nuances of pollutants in smaller municipalities and neighborhoods.

"If you had asked me four years ago, 'What's the air like in Louisville, Kentucky, how much does it vary, and how much could that be related to incidence of certain diseases?' my answer would have been, 'Generally, it's kind of marginal, and I'm not sure how it relates to disease," Ted Smith, chief of civic innovation for Louisville, told BuzzFeed News.

But over the last few years, Louisville residents have discovered new tools with which to gauge air quality: portable, sensor-rich, relatively inexpensive devices that continuously measure the air around them and, in the case of some asthma patients, their respiratory response to it. These gadgets offer an unprecedented breakdown of every breath their users take. And they're providing researchers with a wealth of data about air quality and how it relates to health.

While the data can sometimes be overwhelming in its volume, Smith said it has already proven useful. "There are parts of our community where the air is generally worse than other parts of our our community," he said. "That's new as an insight." And it's one with a possible public health impact: It's inspired Louisville to consider new health initiatives, like concentrating the planting of new trees in neighborhoods with poorer air quality.

As wireless "smart" inhalers from the likes of Propeller Health and Cohero Health grow in popularity and proliferate, they're driving new research into respiratory health. Through one of the first apps made with ResearchKit, Apple's software framework for smartphone-conducted clinical research, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai and LifeMap Solutions are conducting an asthma study through users' iPhones. Separately, the institutions are also testing an app that interprets data from inhalers to help patients monitor their symptoms for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Other small air-monitoring sensors currently available, including the Air Quality Egg and PerkinElmer's Elm, track humidity, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, and other pollutants in the environment.

Some of these devices have caught the attention of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency at a time when federal and state budgets for air monitoring are constrained. "Lower-cost and easy-to-use air pollution sensors provide citizens and communities with opportunities to monitor the local air quality that can directly impact their daily lives," agency scientists wrote in 2013. But these inventions aren't made to live up to federal air-monitoring standards, nor must they track all six of the common pollutants deemed harmful by the EPA: "Data of poor or unknown quality is less useful than no data since it can lead to wrong decisions."

Still, citizen-scientists and government officials have forged ahead with tracking. In a project sponsored by the European Commission, a group of 29 institutions from 14 nations will distribute portable air quality sensors to people in nine cities to assess pollution in those areas.

In Louisville over the past year, officials have bolstered their EPA-installed air quality monitors with more than 30 next-generation devices. And they plan to add 85 more. "Our end game is hundreds and hundreds of these things over time," said Smith, the Louisville government official.

Manufactured by a variety of companies, these newer air quality monitors measure pollutants from particulate matter to carbon monoxide. The data they collect is posted raw to a municipal website.

Louisville's experiment hasn't been without hiccups. The city started out using only Air Quality Eggs, a device launched on Kickstarter, but was forced to add other sensors after concluding the data the Eggs collected wasn't accurate. (Egg engineer Dirk Swart told BuzzFeed News the company has incorporated the city's feedback into an upcoming, more accurate version.) A related effort involving 20 bicyclists outfitted with wearable air quality monitors also ran into data usability problems.

"There's just a lot we don't understand about how air varies and moves," Smith said. "When you have a person that moves within a moving body of air, it's actually very difficult to figure out what's going on."

Indeed, some scientists say that some of these new air quality monitors aren't quite ready to be used in research. "We would so much love to have heaps of sensors that we could network together and measure all kinds of things. With a couple of exceptions, we haven't found sensors that are useful to us," said Suzanne Paulson, director of the Center for Clean Air at the University of California, Los Angeles, adding, "Now, that doesn't mean there are no sensors that work at all."

Still, Louisville has found a lot of success in an ongoing respiratory health study with Propeller Health, whose FDA-approved proprietary sensor has proven to be accurate in clinical trials. When a user with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has trouble breathing and takes a puff on a rescue inhaler enabled with a Propeller sensor, the device captures the time and location of the incident and sends it to an app on the user's smartphone.

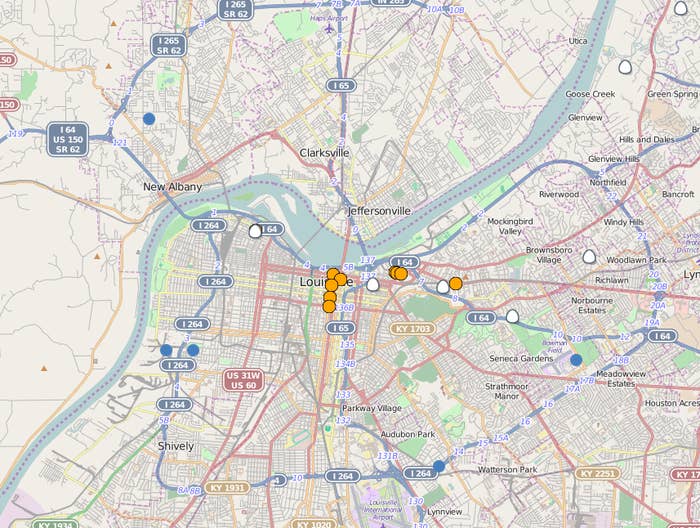

In a yearlong pilot program, 300 people given Propeller sensors logged 5,400 uses of a rescue inhaler. The anonymized data allowed local officials to identify multiple asthma hotspots in Louisville. Folding in other data sets, they also were able to see if local weather, air quality, and other neighborhood characteristics contributed to higher instances of asthma attacks. Propeller claims that participants reported fewer asthma attacks over time by using a map and history of their inhaler use to avoid hotspots.

In March, Propeller said it will extend the Louisville program, now AIR Louisville, for another two years and distribute more than 2,000 additional sensors in support of it. And, as part of President Obama's Climate Data Initiative, the company is embarking on a five-city effort to build what it says will someday be the first-ever national map of asthma risk areas.

"All of a sudden, we have access to data that's never been possible before," Meredith Barrett, vice president of science and research at Propeller Health, told BuzzFeed News.

And this data can have real-world impact. Working with a local pediatrician, Louisville resident Roxanne Jones used Propeller to determine that her daughter's asthma attacks were being triggered by a black walnut tree in a park they frequented. "We knew she was allergic to walnuts — it never dawned on me she was also allergic to the pollen (of the tree)," Jones, 49, told BuzzFeed News.

Once Jones became aware of the scope of her daughter's allergy, the pair kept their distance from that tree and other hotspots. Now, her daughter uses her inhaler a lot less often.

"The sensor would pinpoint on the map which area of the city is having asthma problems," Jones said. "We'd just go somewhere else."