On Jan. 5, a man checked into a hospital’s emergency room in Camden, New Jersey. Because his heart was beating irregularly, doctors suspected he had atrial fibrillation, the most common type of arrhythmia, which can increase the risk of stroke. But to decide how to treat him, they needed to know exactly how long his heart had been acting up.

That’s when one of the physicians noticed a Fitbit Charge HR on the patient’s wrist — and it had the answers they were looking for.

Activity trackers like Fitbits aren’t medical devices, but because they constantly capture enormous volumes of biometric data, medical providers are increasingly finding that, in some situations, they can be useful. The Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center doctors who recently treated the patient with heart problems wrote about their experience this month in Annals of Emergency Medicine.

The doctors believe that this is the first time that activity-tracker data has been used in medical decision-making and reported in a scientific journal. It was an eye-opening experience for Dr. Al Sacchetti, the hospital’s chief of emergency services and a co-author of the case report.

From now on, Sacchetti told BuzzFeed News, “if you’re wearing it, I’m going to interrogate it.”

When emergency responders picked up the 42-year-old man, he’d just had a brief seizure, one in a history of them, and his heart was racing at an irregular rate of up to 190 beats per minute, according to the paper. When he arrived at the hospital, it was vacillating between 130 and 190, at an average of 163. (A normal resting heart rate for adults ranges from 60 to 100 beats per minute.) Then during an exam, a test confirmed the patient had atrial fibrillation, and another dose of medicine helped lower it even more.

Yet the patient and his wife told doctors that he didn’t have any history of heart disease or atrial fibrillation — and he hadn’t felt anything different about his pulse. That can happen, Sacchetti said.

If a patient has been experiencing atrial fibrillation for less than 48 hours, physicians at Our Lady of Lourdes will give them an electric shock — also known as a “cardiovert” — that resets the heart back to its normal rhythm. But if it’s been more than 48 hours, doctors will prescribe blood-thinning medications to prevent blood clots (although anticoagulants have risks of their own, like bleeding more easily). What gets tricky is when patients, like the 42-year-old man, don’t know when their atrial fibrillation actually began.

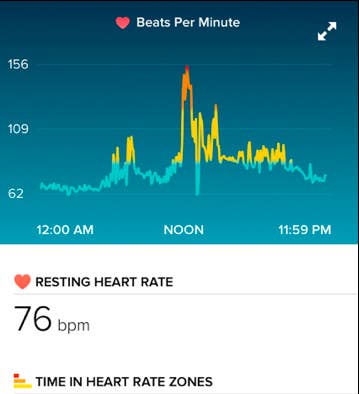

Doctors were planning to give the patient blood-thinners when “[Dr.] Carol McDougall looked and said, ‘He’s wearing a Fitbit,'” Sacchetti recalled. “She asked, ‘Is this a Fitbit that tracks your heart? Can I see your phone?’ They opened his iPhone, went into the app, and said, ‘Look, we can see you went into this three hours ago.’” The Fitbit app showed that the man’s heart rate had been steadily in the 70s before suddenly jumping to 160.

“At that point,” Sacchetti said, “the team that was there said, ‘We’re comfortable cardioverting him.’ He got to go home and didn’t have to go on anticoagulants.”

Fitbits don’t have to live up to the high degree of accuracy that FDA-approved medical devices do, which may make some clinicians nervous about relying on them in potentially life-or-death situations.

In January, the San Francisco company was hit with a class-action lawsuit that accused the Charge HR and Surge of inaccurate heart-rate monitoring, especially during periods of intense exercise. Then again, when Consumer Reports tested those devices on two people on a treadmill, it found the heart-rate monitoring to be “very accurate” in almost all situations, compared with a chest strap with proven accuracy.

In either case, one situation involving one patient is hardly proof of a Fitbit’s accuracy. But Sacchetti said what’s more important to him is the device’s ability to continually record the high-and-low patterns of someone’s heart rate, rather than to be ultra-precise about the value of every single beat. Those general patterns are enough to help doctors draw conclusions about the timeline of an episode of atrial fibrillation, as well as of cardiac arrest, Sacchetti said. And because these devices are worn around the clock, not just when a medical emergency happens, doctors can get a sense of a patient’s complete history.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and the startup Cardiogram are conducting a study to see if the Apple Watch’s heart rate sensors can identify people at risk of atrial fibrillation. AliveCor, which makes a smartphone-connected, FDA-approved electrocardiogram device, is planning to release a special Apple Watch band that can detect the presence of atrial fibrillation.

“There’s lots of patients who present vague complaints we can’t really get a handle on, and everything’s back to normal by the time they get to us,” Sacchetti said. “Now we’ll have something to hang on to — is your heart too fast, too slow, just normal? — and go from there.”