Since Sean Ahrens was diagnosed at age 12 with Crohn’s disease, a largely mysterious and painful condition caused by inflammation of the gut, he’s tried all kinds of diets and drugs. But what he ingested on March 17, 2010, was extreme even for him: a shot glass of parasitic worm eggs.

The experiment came at a desperate time, when 23-year-old Ahrens’ medication had stopped working for no apparent reason. A few of his friends with Crohn’s were trying parasites, citing a theory that didn’t sound crazy — to him, anyway.

Although the causes of Crohn’s aren’t known, one likely contributing factor is that the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells in the gut. “If we actually give the body something to fight against, like a parasite,” Ahrens told BuzzFeed News, “maybe it’ll stop fighting us and maybe it’ll start fighting the invader.”

It wasn’t the first time Ahrens had turned to unconventional, non–FDA-approved treatments. In addition to being a software programmer and two-time startup founder based in San Francisco, he’s the founder of the biohacking community Crohnology.com, where more than 9,000 patients with Crohn’s and a similar disease, ulcerative colitis, discuss remedies ranging from alcohol abstention (“I have lots of tea-time with friends instead of keggers”) to fecal transplants (“worked wonders...my donor was my wife”).

Even by those standards, egg-swallowing was a novel remedy — only a few people in the forums had tried it. Some were convinced it helped clear up their flares. “Worked great for me!” one wrote. “Almost back to full health, during the worm treatment I could see minuscule improvements every week.”

After trying it himself, Ahrens isn’t so sure. Last month, some six years after his strange self-experiment, Ahrens published an essay about the experience, complete with a detailed timeline of his doses and symptoms. And it didn’t appear on a blog or online patient forum, but rather a major medical journal, The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

In the scientific literature, publications written by patients like Ahrens are rare. He sees the paper as vindication that doctors and scientists are starting to pay attention to the online grassroots community of patients and their advocates — “e-patients” — who see themselves as equal partners with doctors rather than passive recipients of the health care system.

Although social media and viral hashtags have started to make e-patients more visible, the medical establishment has been slow to embrace the movement, said Dave deBronkart, who became an e-patient advocate and speaker at TEDx and elsewhere after recovering from late-stage kidney cancer in 2007. He called Ahrens’ publication “an enormous breakthrough, compared to the conventional wisdom that says, ‘What could patients have to offer? They’re not PhDs.’”

Ahrens’ longest and most severe flare occurred in 2010, leading to months of diarrhea, gut pain, colonic bleeding, and weight loss.

The immunosuppressant drug he’d been taking since 2003 had abruptly stopped working. So his doctors recommended that he switch to drugs that needed to be refrigerated and injected daily — an inconvenient option for his frequent travel schedule. If that didn’t work, the next step would be surgery to progressively remove parts of his intestines, a not-uncommon procedure for Crohn’s and colitis patients.

“Hopefully that paints the picture for why someone would do something as seemingly crazy as taking a non–FDA-approved mail-order treatment of worms,” he said.

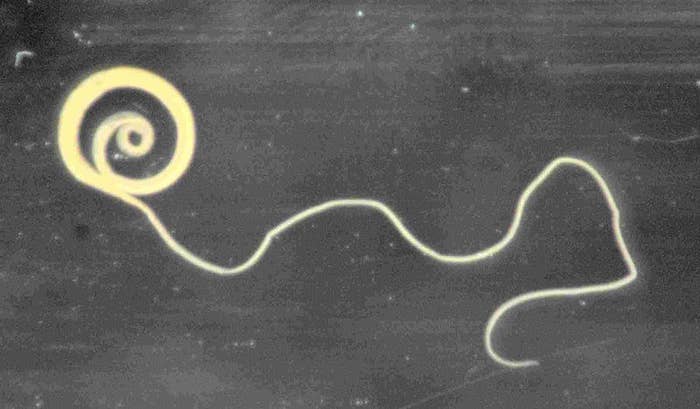

Ahrens had read about a small 2005 study reporting that 13 out of 30 colitis patients had felt better after ingesting eggs of Trichuris suis, a parasite known as pig whipworm. To Ahrens, a bug that usually infects pigs sounded less risky than human hookworms, which two of his friends with Crohn’s had ingested.

Ahrens talked to his gastroenterologist about it, and was told the risks were “probably low,” as he writes in the new paper. (Infections from parasites, depending on the type, can be dangerous: The CDC warns of symptoms ranging from abdominal pain and weight loss to cysts.)

So he went online and paid $3,000 to a German pharmaceutical company for about a dozen vials of 2,500 pig whipworm eggs each. He left them in his fridge for a month as he worked up the nerve.

One evening, he looked at the clear solution under a plastic toy microscope to make sure the eggs were really there. Then, in the kitchen of his Berkeley apartment, with his roommate filming, he tossed back the first dose from a glowing, sparkling shot glass, specially chosen for the occasion. “Super salty,” he recalled.

Immediately afterward, Ahrens filled out a self-created survey on his phone about his symptoms: Gut pain? Bowel movements? Blood in stool? Every two weeks for the next five months he repeated the procedure, taking a dose of worm eggs and then filling out the survey.

At three months in, though, Ahrens didn’t feel like he was improving at all (despite the fact that he had never stopped taking the medication he’d been on for years). So he began a strict, no-grains-or-refined-sugars diet he’d heard about from other patients. By August 15, 2010, when the last parasites were consumed, Ahrens did feel better — but he couldn’t be sure whether it was due to the eggs, the diet, the drugs, or some mix of all three.

“The sad conclusion I have from the whole thing,” he said, “is I don’t have a clear conclusion.”

He paid $3,000 to a German company for about a dozen vials of 2,500 pig whipworm eggs each.

He isn’t the only one with mixed feelings about the treatment. Three years after his experiment, Fortress Biotech, a Massachusetts company then known as Coronado Biosciences, announced the failure of a clinical trial that also involved giving pig whipworm eggs to 125 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s; they failed to show statistically significant improvement or achieve remission. (The company did note, however, that the eggs appeared to be safe, were not a human pathogen, and “were spontaneously eliminated from the body within several weeks after dosing.”)

Ahrens still thought his experience was noteworthy, and in October 2015, he went to Vancouver to speak about it at the International Society for Quality of Life Research conference. On his panel was Brennan Spiegel, who had just become co–editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Gastroenterology. It’s one of dozens of journals published by the Nature Publishing Group, including the prestigious Nature.

Spiegel slipped him a handwritten note, Ahrens recalled, asking if he was interested in writing about his pig whipworm diet in a journal. His response, he recalled, was, “Hell yeah, I didn’t know I could do that.”

Atop the 1,500-word piece was an editor’s note to scientists of a more traditional mindset. “Reading this story will make some of you uncomfortable,” it said. “You might question whether this work belongs in a medical journal or sends the wrong message to readers.”

As a doctor and researcher at Cedars-Sinai Health System in Los Angeles, Spiegel studies digital tools that patients use to track and understand their health, such as wearable biosensors and smartphone apps. Shortly after taking the editing job, Spiegel decided to carve out a space in the journal where patients and their loved ones could relay their experiences in their own words.

Since the “In My Own Voice” section launched early this year, it’s also featured Katie Couric, who wrote about her husband dying from colon cancer. The publisher initially pushed back against the idea for the section, Spiegel told BuzzFeed News, but he and his co–editor-in-chief insisted.

“I think it’s important for our readers to understand that patients can be scientists, too, and can treat themselves, and we have to be aware of stories like that when we go about managing our patients,” he said.

Ahrens now belongs to a small club of e-patients who have managed to break into traditional scientific circles. Some, like him, have published first-person essays about their experiences in the health care system.

Others have inspired full-blown scientific studies. In the 1990s, Caroline McGraw, a mother of four children with gastroesophageal reflux disorder, and Elizabeth Pulsifer-Anderson, who’d started a website and online support group for the condition, convinced scientists to look for possible genetic roots. They found them, and ended up publishing a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Sharon Terry and her husband, Patrick, despite having no scientific background, threw themselves into studying a rare genetic disease, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, after their two children were diagnosed in 1994. By organizing a worldwide association of people with the disease and enlisting scientists to study their DNA samples, the team ended up discovering and patenting the mutation responsible. Today, Terry is an author of 140 peer-reviewed papers and heads the Genetic Alliance, a nonprofit that links patient groups and researchers and runs an online database where patients and scientists can share information in hopes of finding treatments.

Ahrens is still waiting a cure for Crohn’s, or, at the very least, for scientists to pinpoint its cause. For now, he says his health is stable. He still takes the original immunosuppressant medication and tries to avoid refined sugars, gluten, and dairy.

He’s also sure — well, pretty sure — that his body dumped the worm eggs long ago. “I have had a couple colonoscopies since this experiment,” he said, “and at the very least, they’re not in my colon.”

Since the article came out, he says he’s gotten a slew of interested Facebook comments and tweets. He can’t share the full story with friends or family, though, due to a paywall that’s standard in the scientific publishing industry — which, he acknowledges, is a bit ironic, given the crowdsourcing, open-data nature of Crohnology.com. (Ahrens says he hasn’t complained about this to the editors, and understood what rights he was giving up when he agreed to publish; Spiegel says the journal can make articles available to the public on a case-by-case basis.)

Ahrens hopes his experience will inspire others to follow suit. “Every day, patients are acting as their own researchers, and up until now we haven’t had the ability for those researchers to ever publish,” he said. “The patient experience is research, and that research needs to be published.”