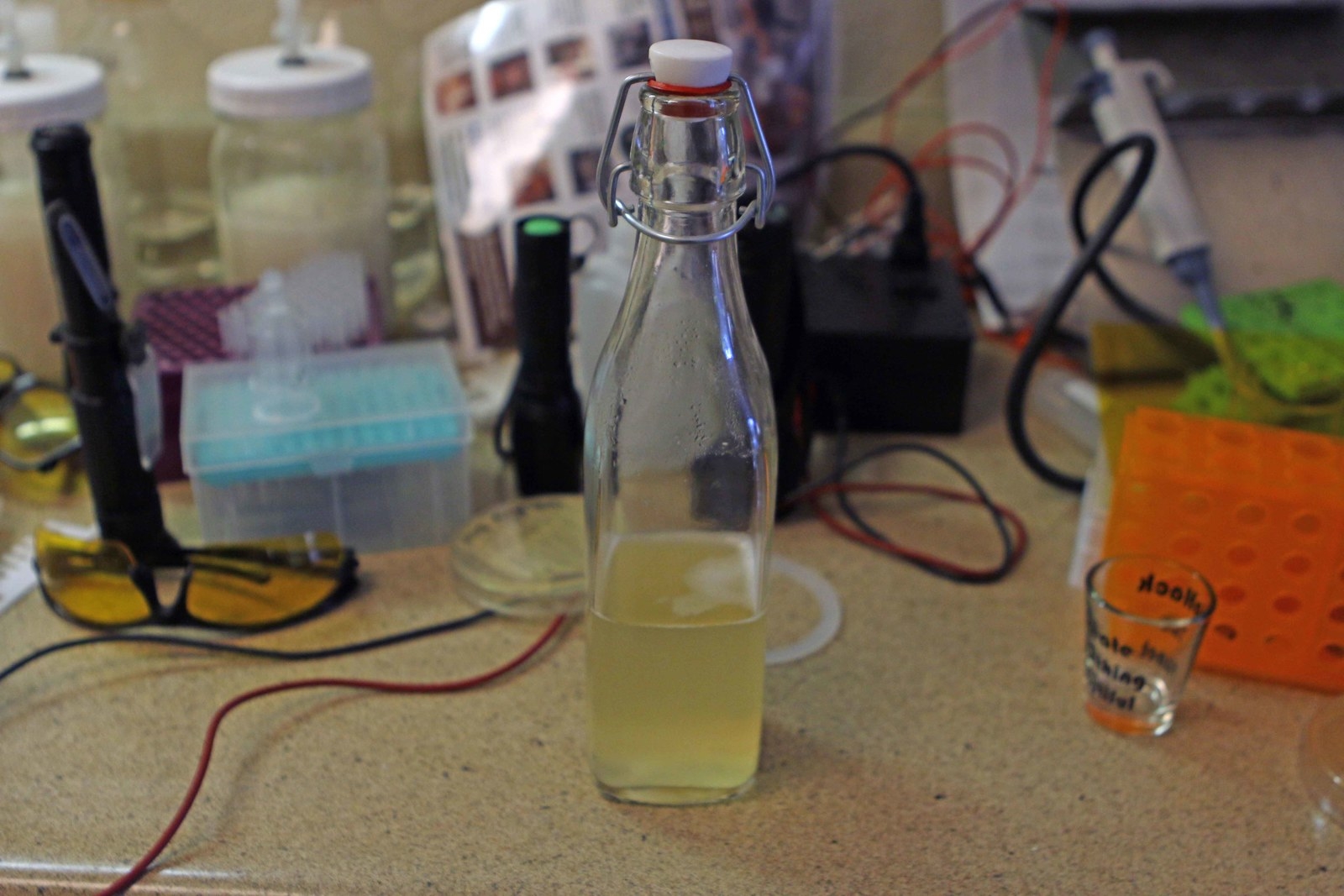

“Don’t be too impressed,” said Josiah Zayner as he cracked open the fridge. On the top shelf, next to Silk soy milk cartons, was the Bay Area biohacker’s latest creation: a bottle of amber-colored booze.

With the kitchen lights turned off, Zayner pointed a blacklight at the alcohol. And a faint green glow sparkled at the bottom of the bottle.

The drink tasted fizzy, faintly intoxicating, and sweet, thanks to the fermented honey that gives mead its alcoholic kick. “I don’t know if you feel like a Viking when you drink mead. I kind of do. Arrrr!” he said, adding, “You can taste the honey, you can taste the alcohol a little bit.”

Zayner, 35, had made the glowing booze partly with a do-it-yourself DNA kit that his startup, the Odin, has just started selling online. The company conceived it as a gimmick to introduce homebrewers to genetic engineering. But in the short time the kit’s been for sale, it’s also become a test for the citizen scientists to see how far they can push the FDA.

With the kit, customers can genetically engineer yeast to make mead that gleams like a lantern — the ideal refreshment for, presumably, poorly lit house parties. “Imagine a world in which after work you invite your friends over to have them try a custom beer you brewed that glows in the dark using your own genetically designed yeast,” the Odin’s website read early last week.

The FDA also began to imagine this world after the kit started selling last week, unknownst to the agency — and then it started asking whether fluorescent homebrew was safe.

By initially marketing the kit as a food-making device, the startup may have exposed a loophole in laws that haven’t caught up to a generation of biohackers tinkering with the DNA of bacteria, plants, and animals in their kitchens and garages.

“The system wasn’t set up to deal with things like this,” said Todd Kuiken, a senior research scholar at North Carolina State University’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center.

While humans have for centuries used yeast to make wine and beer, and homebrewing has been legal federally since 1978 and in all 50 states since 2013, the Odin’s light-up twist could give regulators a hangover-sized headache.

“I can’t imagine when they wrote the laws for this, [they said,] ‘Well, at some point, somebody’s going to be able to engineer yeast for beer that will make it glow in the dark,’” Kuiken said.

Scientific research is traditionally conducted by scholars with multiple degrees and access to expensive equipment at universities and industry labs. But like its DIY bio brethren, the Odin, short for the Open Discovery Institute, wants to make those tools cheap and easy, so everyone can be scientists. Its five employees, who work out of a garage in a suburb across the bay from San Francisco, are used to operating on the fringe of the scientific establishment.

Zayner, the CEO and founder, is a former NASA research fellow with a biophysics and biochemistry PhD from the University of Chicago. Pushing the legal and physical limits of scientific experimentation is second nature for him: Earlier this year, he performed an unsanctioned fecal transplant on himself, using poop from a friend, to relieve gastrointestinal pain. In late 2015, he crowdfunded kits to alter bacteria with the gene-editing technology CRISPR; the Odin, a business he started in grad school, now sells them.

Zayner and his team dreamed up the newest kit as a way to make genetic engineering accessible and useful. Homebrewing, whose popularity has been skyrocketing, seemed like an activity that people would enjoy doing — more so than editing bacteria DNA — and maybe they’d pick up some biology in the process.

“There’s never been anything like this before, where somebody has a kit where they can engineer something they can do something with,” Zayner told BuzzFeed News. “Someone can genetically engineer something they can consume.”

When Zayner set out to advertise the kit, he believed he was in the clear due to what he saw as a legal distinction: the FDA regulates food products, including some alcohol — but the Odin wasn’t selling a beverage.

It’s selling equipment like a pipette and petri dishes, along with yeast and DNA, and providing instructions on how to genetically manipulate yeast cells so they express green fluorescence, the same genetic trait found in jellyfish. Originally, the Odin also instructed homebrewers to add the engineered yeast to water and honey, which the company didn’t provide. Left alone for one or two weeks, the yeast would convert the honey’s sugars into mead, a process called fermentation. Zayner told BuzzFeed News that the result is about 5% alcohol.

“Someone can genetically engineer something they can consume.”

Last week, I visited Zayner at his Castro Valley townhome for a taste test, knowing that what I was about to down hadn’t been FDA-approved. Zayner, who has bleached hair, nose rings, and ears rimmed with piercings, uncorked the bottle with a pop. Then he filled up a pair of shot glasses that said “Biohack the Shot.”

The liquid wasn’t exactly as bright as a glowstick, but under a blacklight, a slight gleam was visible at the bottom where a layer of yeast sediment had settled. Zayner said the three-week-old brew had been more luminous when it was actively fermenting.

“Cheers,” we said, clinking our glasses.

Earlier in the week, Zayner had said that he didn’t know what the consequences of his scientific and business experiment would be, nor was he afraid of finding out. He hadn’t contacted the FDA before making and putting the kit up for sale, originally for $225 and now $199.

“As far as we know, there’s no regulation on stuff like this,” he said, although he conceded that his team may have missed something while scouring the internet. “We’re kind of a small company, we’re off the radar. Does the government even care, would they even care? Even if they did, what would they do?”

It turned out that the government did care. After BuzzFeed News asked Zayner about the product’s legal status, he contacted the FDA, and learned the agency had been waiting for his call. Agency officials held a conference call with Zayner on Thursday. Zayner taped the call with their permission, and shared the recording with BuzzFeed News.

On the call, the two sides went back and forth. Three FDA staffers told Zayner that the green fluorescence protein was likely a color additive for food, and it hadn’t been recognized as safe to consume; Zayner questioned whether it was really a “color” additive when, he noted, the green glow was only visible under a blacklight. Zayner argued that the kits were being sold in part as an educational tool; the FDA disagreed.

“If we did continue to sell these kits, what would you guys do?” Zayner asked during the call.

Jason Dietz, an FDA policy analyst, told him that the agency could issue a warning letter or, at the extreme end, seize the company’s equipment — “that would be unlikely, I would hope,” he added. “Typically people, when they find they’re doing something unlawful, correct it, because it’s not good for business.”

By the next day, the Odin had tweaked its website. It revised its instruction manual to remove all mentions of using the yeast to ferment mead. Gone from the product page, as of Monday morning, was a photo of a full bottle of mead and most of the alcohol references, although the site still said that this type of yeast is meant for mead. It also said, “We see a future in which people are genetically designing the plants they use in their garden, eating yogurt that contains a custom bacterial strain they modified or even someday brewing using an engineered yeast strain.”

Although he would go on to make the changes, Zayner, ever the provocateur, felt compelled after the call to point out to BuzzFeed News all the limits he saw to the FDA’s logic. He wondered: How could regulators justify potentially seizing his yeast when yeast, on its own, isn’t a food product? The Odin didn’t want to harm anyone, Zayner said, but why was the FDA worried about one fluorescent protein when studies show that beer yeasts in general have been evolving and mutating on their own for centuries?

FDA spokesperson Megan McSeveney told BuzzFeed News on Friday that the agency “does not have enough information at this time to determine the regulatory status of this product.” She added that food manufacturers are responsible for complying with federal, state, and local laws.

On Monday, Zayner wrote a blog post in which he backed down even more from the language used in the original advertising. Yeast made with the kits, he wrote, had not been FDA-cleared for consumption. “However,” he wrote, “we believe that there might be people who would attempt to use our kits to create alcohol against the FDA’s wishes so we wanted them [to] be knowledgeable about the product.”

He added that the company planned to seek FDA clearance.

Provided that the federal agency approves, Zayner also hopes to make glow-in-the-dark beer the next craft brewing sensation. The Odin has teamed up with Inoculum Ale Works, a sour-beer brewery near Tampa, Florida that wants to make and sell the beer next year, perhaps online and in its future taproom. The brewery says it also plans to make beers genetically engineered to have citrus flavors, for example, or include a nutritional compound called squalene.

Inoculum CEO and co-owner Nick Moench told BuzzFeed News that, having spoken to some FDA staff, he’s confident that he and Zayner will be able to show that the green fluorescence protein is safe to consume. “This isn’t a small undertaking — it’s going to take some resource[s] and perseverance,” he said via Gchat. “Fortunately we’re swimming in perseverance.”

The Odin isn’t the only company that’s genetically altering yeast to make food. Swiss company Evolva has created synthetic vanillin, the vanilla flavor in ice cream and cake, which prompted the environmental activist group Friends of the Earth to condemn it as an “extreme form” of genetic engineering. Other Bay Area biohackers are engineering yeast to make vegan cheese.

They all aim to create foods that are essentially identical to their conventional counterparts. “The idea with those things is you have a new way of producing it, but the product is chemically the same,” said Gregory Kaebnick, a research scholar at the Hastings Center, a bioethics think tank.

Glow-in-the-dark booze, however, would look quite unlike conventional homebrews — and that’s where the startup would potentially clash with the FDA. Before any substances, including color additives, can be added to food for sale, the agency requires them to either be approved by the agency, or be already generally recognized by experts as safe to eat.

Approved substances are listed in a federal database. Green fluorescence proteins are not on that list.

“Obviously, the Odin folks, they’re not interested in making people sick, they’re not deliberately trying to make something dangerous,” Kuiken said. But “from the FDA’s standpoint, that is probably something that they’re going to want to take a look at, because it hasn’t been looked at before.”

If a food item made with the Odin’s kit were to sicken people, Kuiken worries that the emerging biohacking community could suffer. Glowing plants, fecal transplants, and other boundary-testing science projects have similarly sparked debates over what ethical responsibility independent scientists have to police themselves.

“We’ve seen in the past when particularly some biotech companies just ignore the FDA, they can come down on them really hard, to the point where the companies can get shut down,” Kuiken said. “That’s something I think we’re all trying to avoid happening, and we want to encourage this kind of exploration, but it also needs to be done responsibly.”

Zayner, on the other hand, doesn’t think that cautious behavior necessarily benefits the DIY biotech community. Taking risks expands the possibilities of what they can do.

“It’s better to ask forgiveness than permission,” he said, “because they’re always going to say no to everything.”