Arjun Kumar currently focuses his malevolent energy on one thing alone: fighting Muslims.

Like most Hindu men of his age in Meerut, he grew up detesting them. A city of 42 per cent Muslims and 58 per cent Hindus, Meerut has long been classified as ‘riot-prone’. Its first sectarian riot was well before Partition, in 1939, and its most recent in 2015. News reports always pin the blame on a random incident—Hindu and Muslim college boys got into a scuffle; a Muslim man married a Hindu woman; Muslims encroached on Hindu property—but researchers have suggested the existence of an ‘Institutionalized Riot System’.

In a city where Hindus and Muslims are comparable in numbers as well as economic and political influence, Hindus find it harder to coexist with Muslims than elsewhere in India.

In 1987, in a horrifying incident of sectarian violence, a company of all-Hindu paramilitary men stormed into a Muslim colony, picked up forty-five men, drove them to the bank of a canal, lined them up, and shot them one by one. Only three survived.

Sectarian hate is often the first strongly felt emotion for a boy in Meerut. Kumar despised Muslims before he could count to ten. He has felt furious every time a gang of Muslim boys won a fight on his street. He has choked with frustration every time a Muslim man bought a house in his colony. He has burnt with anger every time a Hindu girl in his colony went out with a Muslim boy.

When the local chapter of the Bajrang Dal vowed never to let another Muslim man woo a Hindu woman again—they call it ‘love jihad’—Kumar jumped right in. Since then, Kumar and his gang receive an alert from head office if a Hindu girl is sighted with a Muslim boy. His job is to make sure they don’t meet again. Fortunately, this is a process that involves a degree of violence, since that is the bit that Kumar likes best.

Roaming the streets on his motorbike every Valentine’s Day, he keeps a special eye out for Hindu-Muslim couples. "Last year was fun. I had been watching this guy for a month and it’s on that day I finally see him with a girl from Dharampuri walking hand in hand in Gandhi Park. I was unstoppable."

Today Kumar has what he hungered for as an adolescent lining up for the Bajrang Dal’s recruitment parade: izzat. "If I stand at any place in Dharampuri, there will be a long line of men behind me in no time."

What does a young man in Meerut desire after he has achieved that? Kumar will be out of college in 2017, with a bachelor’s degree in commerce and no idea of what to do with it. Thousands of other young men in Meerut will be in the same position.

Kumar already feels anxious about the future—he can’t go back to being irrelevant. There is only one way for him to go and he knows it.

"I am thinking of politics," he said, after a deep sigh of contemplation.

Arjun Kumar is what think pieces explaining the Trump and Brexit verdicts term a loser of globalization, one of the millions of leftover youths whose anger is transforming world politics. It’s like the world swept past him while he was arranging chairs in the Bajrang Dal office.

Kumar is not sure he will find a job he’d like or find a girl who’d like him. On an elemental level, he doesn’t know if he matters to the world. There’s only one way left for him to make that happen: punish everyone who’s moved ahead of him in that queue.

This is what he thinks politics is about. He knows only one party that will allow him to practise it.

Kumar has stopped going to college altogether. "I divide my time between hanging out at the offices of the ABVP, BJP and VHP—two hours here, three hours there. It’s how my days go."

Two months ago, when the BJP organized a mega convention in Meerut, Kumar did his best to be visible to the high and mighty of the Hindutva establishment. "Twenty-five thousand people were there. Very important people—you can say celebrities." Kumar spent his whole time there ‘making connections’. He picked up his phone from the table and began to recite the names and numbers of people who "personally know him" now. He wanted me to note down these details. He said all I had to do if I needed them to do something for me was drop his name.

I asked him why politics. "To serve the nation," he said with a straight face.

But one doesn’t just become a politician, I said. He laughed his first laugh of the day.

I shouldn’t underestimate him, he said. He had a plan. It was to follow the track of a man whose plan had worked. Sangeet Som first won a state assembly seat as a BJP contestant from Meerut district in 2012. But that’s not his claim to fame.

In 2013, months before parliamentary elections in which the BJP eyed Uttar Pradesh, the young MLA circulated a fake video through mobile phone networks to spark off sectarian riots in western UP in which fifty people were killed and 50,000 displaced. He’s been a role model for Meerut’s young Hindu men ever since.

"I follow him around every time he comes to Meerut," said Kumar.

There’s another reason Kumar gets to observe the MLA at a close distance. Som has recently hired a personal tutor to teach him to speak English—the man happens to be Kumar’s older brother.

Why does a man who seems to have made a political career out of pitting Hindu boys against their Muslim neighbours need to speak English? For a simple reason, Kumar explained. Sangeet Som can use his success in politics as the shortcut to the good life he would otherwise have spent a lifetime chasing, but the world will still see him as a provincial wannabe unless he speaks the language of privilege. It’s the language he will need to speak when he is travelling abroad, meeting dignitaries, mingling in high society.

From the rumours Kumar has heard in Meerut, Som’s long-term plan to develop his personality include getting an MBA degree from Australia. Kumar can’t speak fluent English himself, but he isn’t too bothered about it yet. He has more important things on his mind. Building his political image tops the agenda.

The work has begun on the platform best suited to his needs: Facebook. Kumar has six Facebook accounts altogether, each targeted to a different audience, from his gang of boys in Meerut to the global soldiers fighting "love jihad". He keeps them active 24/7, often staying awake the whole night.

I ask him if he has any time left for a personal life. He glares at me bewildered.

Girls, I specify. "Do you like girls?"

Kumar tells me he likes to "stay away from girls". His friend almost snorts out his Coke.

"He had a girlfriend," the friend explains, "but she left him for another guy—a rich guy."

"True?" I ask Kumar. "Girls," he says, his eyes on his phone screen once again, his mouth twitching, "they are not worthy of trust."

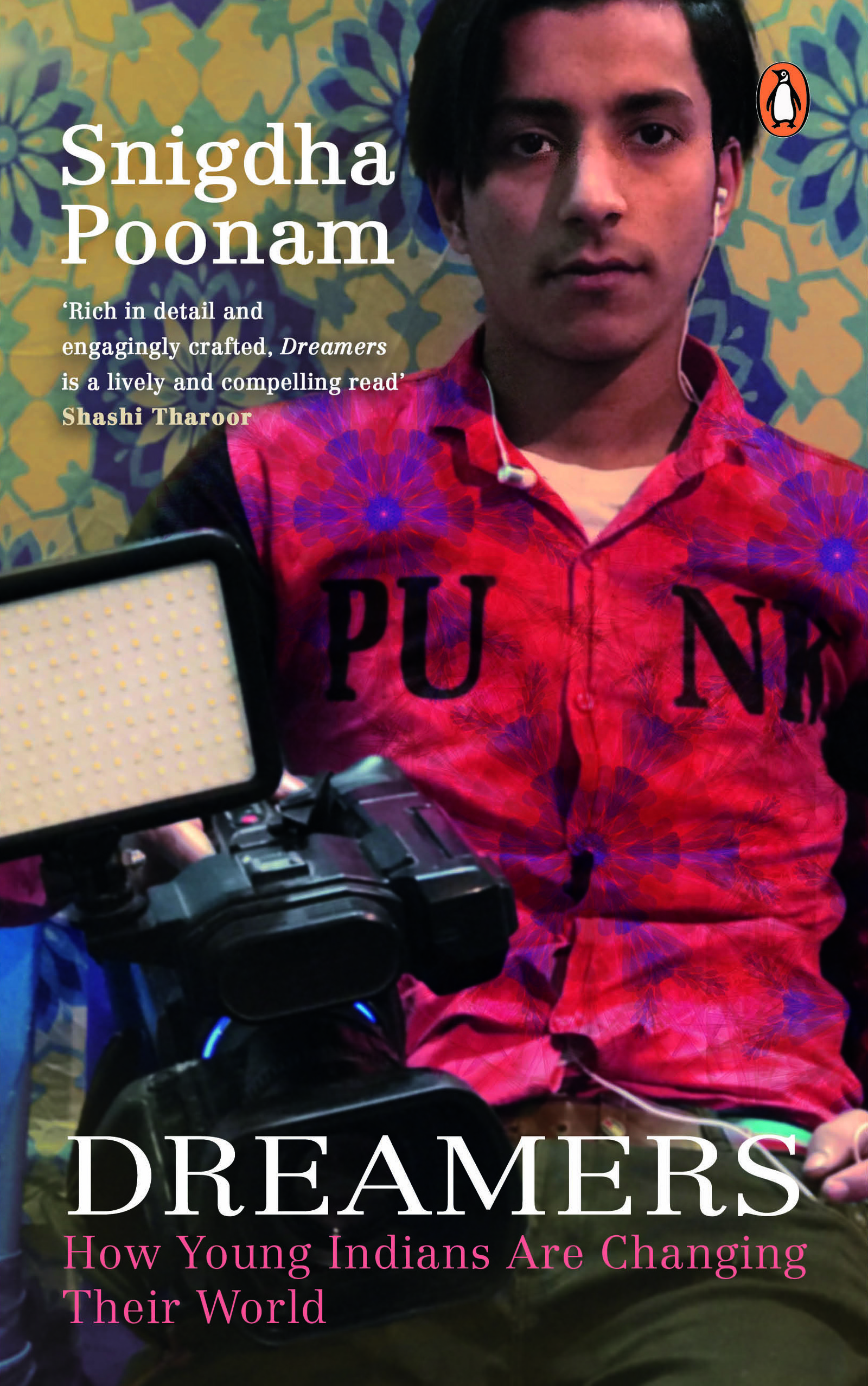

Excerpted from the book Dreamers: How Young Indians are Changing the World by Snigdha Poonam, published by Penguin/Viking.

Snigdha Poonam is a journalist based in New Delhi. Her work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, Caravan, Granta and other publications. She currently reports on national affairs at the Hindustan Times. She won the 2017 Journalist of Change award of Bournemouth University for a work of reportage that appeared on Huffington Post.