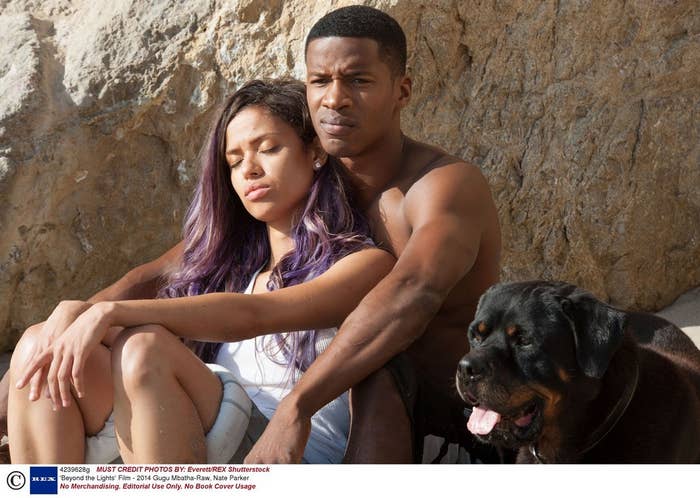

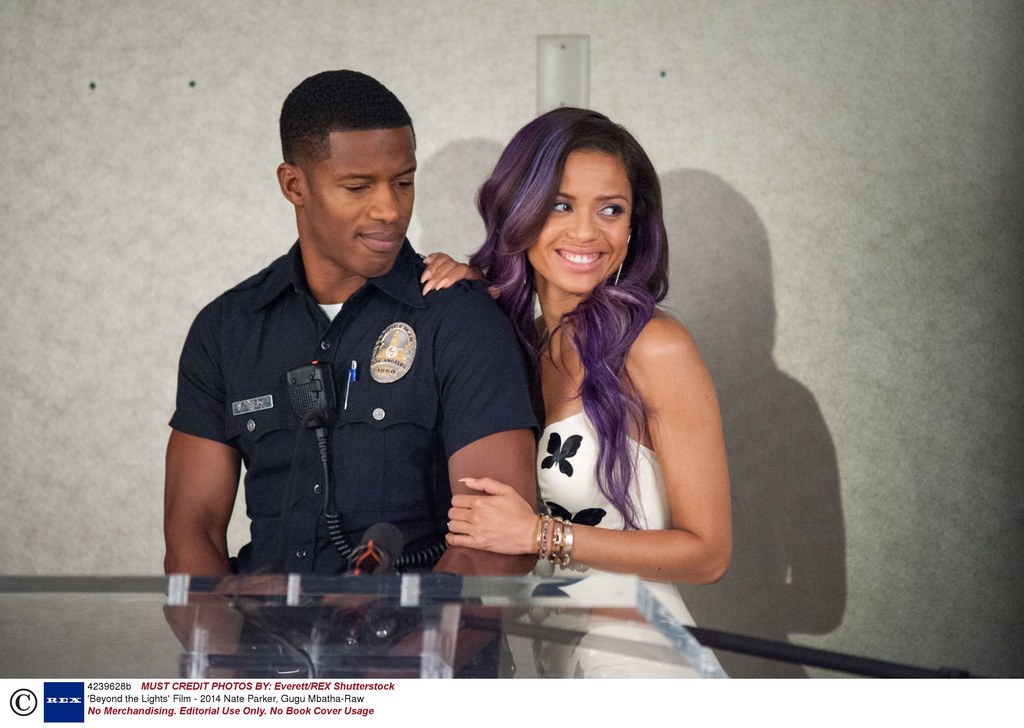

Beyond the Lights begins in south London. Macy, a single mother, cheers on Noni, her mixed-race daughter, as she sings Nina Simone's "Blackbird" at her primary school talent show. Noni's talent carries her all the way from Brixton to Beverley Hills, landing her a career as a pop star. Later, over the closing credits, Londoner Rita Ora's Oscar-nominated song "Grateful" plays. Noni's British identity is threaded throughout the film, her fish-out-of-water quality only emphasised by her British accent. If Britain has such a presence in this film, then why is it that almost a year after its release in the US, most British audiences have yet to see it?

The mother and daughter in Beyond the Lights are played by British actors Minnie Driver and Gugu Mbatha-Raw. The latter joins a long – and ever-expanding – list of black British actors (from Marianne Jean-Baptiste to David Oyelowo) who have left London for Los Angeles. An ongoing discussion about the implications of such an exodus for the British film industry is taking place, but it isn't just black actors Britain is losing out on – it's black films, too.

Here in the UK, Beyond the Lights is available to rent or buy on iTunes, Amazon, and DVD. However, if black Britons want to see this film on anything bigger than a laptop screen, they had better look elsewhere. Its director, Gina Prince-Bythewood, made the seminal and beloved romantic drama Love and Basketball; she isn't a first-time filmmaker whose name and inexperience represents a gamble. Relegating Beyond the Lights to home release means it runs the risk of getting lost among the cacophony of options in an already-overcrowded VOD market. Refusing to release it theatrically and promote it properly is lazy; denying black audiences the communal experience of seeing themselves and their stories validated on the big screen is insidiously dismissive.

With the exception of historical dramas like Selma, The Butler, 12 Years a Slave (the latter backed by British production company Film4) and Kevin Hart comedies, a whole slew of films like Beyond the Lights are making their way over to UK cinemas at a snail's pace – or, more commonly, not at all.

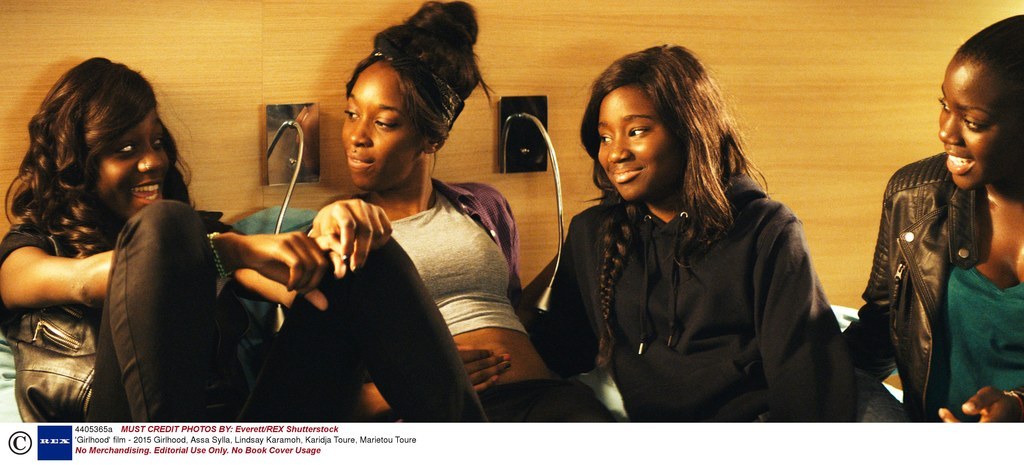

The road to a theatrical release is fraught with complications for a contemporary black drama, with films forced to rely on festival screenings (Pariah), self-distribution (An Oversimplification of Her Beauty), and streaming deals with platforms like Netflix (Ava Duvernay's The Middle of Nowhere) in order to reach audiences. Even the critically acclaimed Fruitvale Station struggled to secure a distribution deal, ending up with a limited theatrical release of just 40 screens in the UK almost two years after its 2013 premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. Beasts of the Southern Wild, Gimme the Loot, and Girlhood have fared a little better at the cinema – but it's no coincidence that these films were made by white directors. The suggestion seems to be that black lives only matter when they are filtered through a white auteur's lens.

With a cast including such well-known names as Minnie Driver and Danny Glover, plus an 81% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes (higher than both Jurassic World and Pitch Perfect 2), the decision to limit Beyond the Lights to home release seems at best misjudged and at worst a wasted opportunity. In an effort to understand why the film headed straight to DVD, film critic Robbie Collin reached out to the film's UK distributor, Universal Pictures. Collin was told that the combination of the film's "theatrical under-performance in the States," the cast's limited availability ("for promotional duties"), and the UK's "crowded summer marketplace" were all factors in the decision-making process.

Box office expert Charles Gant explains the bottom line. "By rule of thumb, films in the UK should take one-tenth of the number achieved in the US, but with the dollar sign switched to a pound sign." For black films coming to the UK, distributors' box office expectations are even lower. The Best Man Holiday, which made $30 million in its US opening weekend was expected to make £3 million in the UK. Instead, it made a mere £134,000, after opening on 122 screens. Even films with a bankable black lead are not guaranteed success; The Equalizer, to take a recent example, stars Denzel Washington and opened on $35 million in the US. Its expected UK box office of around £3.5 million was optimistic: it opened at just under £2 million.

Yet this is hardly the rule, with films led by stars like Will Smith corresponding with Gant's formula. Smith's most recent blockbuster, After Earth, opened on £2 million in the UK, comparable with its $27.5 million opening weekend takings in the US. To suggest that race is the primary reason why the films underperformed in the UK is to ignore other factors, such as The Best Man Holiday's largely unknown cast or the fact that The Equalizer is a remake of an '80s TV series (that already had limited UK appeal despite a white British lead). A problem arises when such examples are taken out of context and used to reify expectations about a black film's box office potential, when in fact there seems to be no hard and fast rules when it comes to what makes a black film bankable.

The Biggie Smalls biopic Notorious, and Kevin Hart's Ride Along, reached a broad and ethnically diverse audience – and made healthy profits in the UK. This is the direct result of UK distributors Fox and Universal committing to a solid marketing spend. Films like Beyond the Lights "require nurturing and attention," says Gant, suggesting it "might've fared better under a smaller indie distributor."

For many years, UK distributors have been more cautious about films featuring black protagonists, says Gant. Even writer-director Tyler Perry – a pioneer of modern black cinema in America – has struggled to gain traction in the UK and across Europe. Perry has created a secure niche for himself in the US, his popularity with black audiences leading to him to establish his own distribution subsidiary in partnership with Lionsgate. Here in the UK, neither Perry nor his audience have such equivalents.

Where a 2013 study reported that 46% of US cinemagoers were non-white, the BFI's Statistical Yearbook reports that 9.4% of UK cinemagoers in 2014 were black and minority ethnic. Out of context, it's easy to see why the numbers make UK distributors nervous. Yet the BFI says BME groups are actually over-represented in ticket sales: With proper care, attention and audience development funding – as well as content that actually reflects the broadness of black life – the captive audience of BME cinemagoers is ripe for growth.

However, an age-old logic persists: If black audiences make up only a small percentage of cinemagoers, why should distributors and exhibitors cater to them? On the other hand, if black films aren't being screened, how can film executives expect black audience numbers to improve? The myth that black people don't go to the cinema becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, predicated on the assumption that cinemagoers are only interested in seeing themselves represented on screen. This seems to be at the heart of the problem.

Film critic Ashley Clark maintains that unless gatekeepers make an active effort to diversify, these problems will persist: "I think executives and gatekeepers have to want to change the landscape, and serve the filmmakers in the most effective way, from marketing to distribution. But do enough of these powerful people really want to? I'm not sure."

There are a handful of Brits who are working to prove there is an appetite for original stories about black lives here in the UK. Priscilla Igwe of The New Black Film Collective rescued Justin Simien's sharp teen comedy Dear White People from a straight-to-DVD fate. Igwe explains that TNBFC – a network of film exhibitors, educators and programmers rather than a traditional distribution house – were able to step in and snap up the theatrical rights to the film for "next to nothing" after it had been passed around several UK distributors like an unwanted hot potato.

Elsewhere, Film4 partnered with Kaleidoscope Films to put on four special screenings of black British director Debbie Tucker Green's Second Coming across London, Nottingham and Bristol. The screenings sold out steadily proving that the combination of targeted programming and careful marketing can ensure theatrical success. In Scotland, Edinburgh International Film Festival's artistic director Mark Adams programmed two screenings of Beyond the Lights as part of this year's festival. In an interview, he explained the "risk" of programming black films, stating, "It's a known issue that dramas with majority black casts don't perform well in Britain."

"Most distributors are white middle-class people selling films to other white middle-class people," says Igwe. "Films like Girlhood and Fruitvale Station were not promoted to black audiences."

"I always hear the same rationale: Audiences won't go for black films – especially black films that aren't comedies or action – and that they're too risky to really get behind, financially," says Clark. "But I think that type of attitude, whether it's conscious or subconscious, enables the status quo; an attitude which, for me, is typically temperamentally British."

Film programmer (and relative of director Amma) Jan Asante set up Brixton's Black Cultural Archives Film Festival in an attempt to "fight a monolith" of black films that depict black lives as anchored in crime and poverty. "The word 'urban' obfuscates family, love, romance, intellect," says Asante, who aims to bring a broad range of black films to cinema screens.

Historically, there has been a troubling conflation of "urban" and "black film." The original poster for Second Coming, featured a pair of curtains behind a close-up of Idris Elba; for the iTunes page, the curtains had been transformed into a high rise tower block. The film itself, an elegantly low-key riff on the kitchen sink drama, actually makes no suggestion that Elba and his family live on a council estate.

Black British director Destiny Ekaragha also ran into difficulties when trying to secure distribution for her first feature Gone Too Far, which was released in 2013. "People were scared of it. There is a narrative of blackness that is accepted, and it involves drugs, crime, and black boys who wear hoodies." Ekaragha recalls a chat with someone from a distribution company about the film, a comedy of manners about two brothers, in which she was told it would be a hard sell. "One of the feedback notes we got back on the film – the best one, I wish I'd framed it – said, 'How come the brothers don't kill each other?'"

"By saying that there is no audience for black films, you are saying that those stories are not human," says Ekaragha. "They're Other."

It's telling that Dear White People was passed over by experienced distributors, landing with a community collective with a self-proclaimed educational aim to highlight films of black representation – and without the means to secure the film a wide reach. Until financiers, distributors, and exhibitors commit to investing in and mainstreaming black stories, black audiences will continue to be fed the bitter pill that their stories actually aren't worthy of being told.